I find myself recounting this story, or mentioning it in passing, every time I discuss Triumph motorcycles or even list one for sale (I recently sold my Triumph Tiger Sport 1050). So I’ll get it down in writing.

Whenever you start looking at modern Triumph motorcycles with old names — like Bonnevilles, Tridents, or Tigers — there’s a certain kind of motorcyclist that will mumble “Harrumph” and make a muffled claim that modern Triumph isn’t the same as the old one.

But we younger folk (of which I’m one, for this example!) don’t really know what this is about. If you’ve only looked at bikes since the 1980s, which is the period in which I’ve existed in fleshy form, then apart from vintage bikes, all you’ve known is modern Triumph, sometimes called “Hinckley” Triumph or “John Bloor’s” Triumph.

Modern Triumphs often share names with old ones — Bonneville, Trident, and Tiger brands have been around forever. Plus, some of them bear more than a passing resemblance to bikes from times gone past — something Triumph capitalises on constantly.

So just what is going on? How has modern Triumph evolved from the older one? What do they have in common, if anything? And is there anything wrong with the new Triumph? Let’s look at this in detail so other newbies know what’s going on.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

Phase 1: Triumph Engineering

The original Triumph company was actually even earlier than “original Triumph”. A German man by the name of Siegfried Bettmann emigrated from Nuremberg to Coventry in 1883, and founded a trading company in 1884, at the age of 21. He was importing bicycles, and so renamed the company the Triumph Cycle Company in 1886, then as New Triumph Co. Ltd in 1887, after getting funding from Dunlop.

Bettmann took on a partner, Moritz Schulte (another person from Nuremberg), who encouraged Bettmann to get into manufacturing. Together, with borrowed money, they bought a site in Coventry and started producing Triumph-branded bicycles. In 1898 they decided to extend production to include motorised bicycles, and produced their first one in 1902.

Triumph’s first motorcycle was the Triumph No. 1. It was a bicycle with a 2.25hp Belgian Minerva engine. Triumph was born!

This first Triumph motorcycle is pretty much the equivalent of a modern e-bike. It even has pedals! It makes me wonder where today’s e-bike manufacturers will be tomorrow… Are we going to see chromed-out Sur-ron and Zero power cruisers a few decades from now?

After selling more than 500 motorcycles, Triumph started producing motorcycles at its other factory in Nuremberg. By 1905, they had made their first in-house designed motorcycle, and sold more than 250 of them that year.

Those of you with an astute sense of history are thinking, “Germans, eh? Nuremberg, eh? 1905, eh? Whose side were they on?” Well, Triumph was a British company, and so the beginning of the First World War saw them producing motorcycles for the Allies (whew). They produced more than 30,000 models of a motorcycle known as the “Trusty Triumph”, or the Model H Roadster.

Some credit Model H as the original motorcycle. It didn’t have pedals, after all! The Model H Roadster was carburettor-fed, had 550 ccs from a single pushrod-actuated engine, an air-cooled cylinder, and a belt final drive. It did have a 3-speed transmission and even had front suspension (a spring fork). Triumph produced some 57,000 of these through 1923, after which it was discontinued. If you have seen one, it was probably in a museum.

The next few decades were turbulent, with some experimentation in business, and the impact of the Great Depression and World Wars.

The 1929 Great Depression hit hard. Triumph sold off its German subsidiary, and sold another part of its manufacturing to the Raleigh Bicycle Company. The company struggled. Bettmann, the original founder, was forced out of the job of chairman in 1933. In 1936, Jack Sangster, owner of the rival Ariel motorcycle company, bought the motorcycle operations out for 50,000 pounds.

(I say “motorcycle operations” because Triumph had experimented with car production, buying the Hillman car factory in Coventry. The car division was made into a separate company, went bankrupt, and was acquired by the Standard Motor Company. Fun fact, our family used to own one of these. We weren’t old. It was just a very cheap, very unreliable car, that we got basically for free and which always had to be push-started, and which we sold in the 1980s for $150 to a guy who may have had a few too many and crashed it almost immediately, abandoning it and walking home.

Sangster brought some of Arield’s engineers over to Triumph to improve the product range, and was responsible for producing the Triumph Speed Twin in 1938.

“Speed Twin, I’ve heard of those!” cries many a newbie to Triumphs. You might not realise it if you only started following Triumph recently, but we didn’t have Speed Twins for ages. The company actually only brought back the brand in 2019, first with the 1200, and a few years later with the 900.

The Second World War was catastrophic for Triumph. Germany bombed Coventry heavily during what has become known as the Coventry Blitz, from September 1940 to May 1941. The city was virtually destroyed. But Triumph managed to recover tooling from the site and restarted production at a new plant in Meriden, Warwickshire, in 1942.

In 1951, Sangster sold Triumph to BSA (another competitor) for 2.5 million — a pretty good ROI!

Phase 2: The Meriden Era

The Meriden factory era, mostly under the direction of BSA (of whose board Sangster joined), is what most of us think of as “old Triumph”. Sometimes it’s just called “Meriden Triumph”.

Triumph borrowed heavily in this period, but also thrived.

Early Triumph focused on speed records and racing success. This may come as somewhat of a surprise to modern Triumph owners who know that their bikes are high-performance but don’t hear of Triumph winning races like MotoGP or World Superbike Championships.

Well before the Meriden era, at the Isle of Man TT, Triumph placed second in 1907 (second comes right after first!) with Jack Marshall at the helm. In fact, he only came second after suffering a twisted ankle in a fall. (See some pics of that race here.)

Back in the Meriden age, in 1969, Malcolm Uphill became the first rider to lap the Isle of Man at an average speed of 100 mph — over double what Triumph was doing in the early days — on a production bike. The 100 mph average speed record had been set a decade earlier on non-production bikes by another manufacturer.

Triumph also set speed records. Triumph’s most famous record is the one set in 1955, when rider Johnny Allen rode a purpose-built “Devil’s Arrow Streamliner” to set a record on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah at over 193 mph (310 km/h).

But the photo everyone thinks of is from the previous year, of Jack Dale, who stripped down to his swimming trunks to make his Triumph Thunderbird more aerodynamic. He hit 148 mph (238 km/h). Not bad.

Triumph also proved itself in endurance racing. The Thruxton 500, a 500-mile slog in England, was won by Triumphs often enough that the name stuck. That race is the reason we still have a Triumph Thruxton today — not because it sounds cool and a bit like “thrust”, I guess, but because that name earned its place.

Of course, there’s also the famous Marlon Brando placement. Triumph became almost synonymous with 50s masculinity when Marlon Brando rode a 1950 Thunderbird 67 in the 1953 film, The Wild One.

Triumph had started exporting to the US in 1936 (under Jack Sangster’s direction), and it quickly became Triumph’s most important market. After the end of the war, over 60% of Triumph’s production was shipped to the United States. In fact, Triumph couldn’t satisfy all of the US market’s demand.

Being unable to meet demand and having their sales heavily concentrated in one market made Triumph susceptible to being thwarted easily. You want a crazy fact? In 1969, 50% of the US market for motorcycles over 500 cc belonged to Triumph! How did they drop the ball on that? It’s a bit sad, really, but it is also a cautionary tale, in retrospect.

Despite owning the market, Triumph didn’t invest in new tech, continuing to build motorcycles with pushrods (rather than overhead cams), without electric starters, and using a labour-intensive production process.

It’s not like Triumph was some stone-age company, by the way. They were responsible for many innovations in early motorcycles, including:

- Gearboxes: Triumph introduced the first two-speed gearbox in 1913 and a pedal-operated three-speed gearbox in 1915.

- Aluminium Pistons and Improved Lubrication: Triumph was among the first to adopt aluminium pistons in 1920, which helped reduce engine weight and improve thermal efficiency. Alongside this, Triumph motorcycles introduced advanced lubrication systems, enhancing engine longevity and performance.

- Four-valve head: Triumph released the Triumph Ricardo in the 1920s with a four-valve cylinder head to focus on top-end power and speed.

- Suspension: Triumph introduced a rear spring suspension setup in the 1930s while most other motorcycles were still using very basic suspension systems.

But that was obviously a long time before Japanese competition, and it wasn’t enough. Japanese companies were doing so much more.

The most important sign of significant trouble came in 1969 in the form of the Honda CB750: a four-cylinder motorcycle with disc brakes and engine casings that didn’t leak (which, it turns out, is a feature). Triumph had released high-performance triples, but the Japanese bikes were more reliable and less leaky. (See here for more about the Honda CB series.)

Triumph tried redesigning their bikes in 1970 to compete with the Japanese models (mostly Honda and Kawasaki at the time), but it wasn’t enough.

The Decline years

The subsequent phase of Triumph’s history was a sad one.

When BSA Group lost 8.5 million pounds in 1971, it had to take grant money from the British government. BSA sold Triumph to Manganeze Bronze Holdings, a holding group that owned a bunch of other brands, including Norton, Matchless, and Villiers (and some others I don’t recognise). BSA Group itself went bankrupt in 1972.

The British government had the chairman of Norton Villiers, Dennis Poore, take control of BSA/Triumph, which were merged under a new company, Norton Villiers Triumph (NVT). The first action Poore took was to announce he was closing the Meriden factory as of 1974, planning to concentrate production in Birmingham.

Thus began the most turbulent period. The workers at the Meriden factory demonstrated against relocation to the BSA site in Birmingham and ran a sit-in protest for eighteen months.

The protesting workers barricaded and occupied the plant and refused to leave. They did continue producing motorcycles, but sporadically, delivering some late and some not at all. During the occupation, fans and owners came to the factory to show support, some bringing their motorcycles to be repaired, which the workers did for free.

Eventually, NVT agreed to sell the factory back to the workers, which was a dream for them. The workers at the Meriden factory formed Meriden Workers’ Cooperative, and together, they co-owned the factory, producing motorcycles and selling them to their one customer — NVT.

But NVT collapsed in 1977. Following that, the cooperative bought the marketing rights for Triumph with more government loans, forming Triumph Motorcycles (Meriden) Limited. Finally, the brand belonged to the workers!

This article in The Guardian puts it elegantly: “The legend of Triumph and Meriden is based on the sincerely-held conviction among the workers that, no matter how badly dented the British motorcycle industry may be as a result of Japanese market penetration, they still make the finest motorcycles in the world.”

Unfortunately, this didn’t change the economic reality of Triumph’s woes. They were still inefficiently producing outdated motorcycles for a dwindling market, and trying to repay massive loans needed to get them started. Their motorcycles sold well for what they were, but they weren’t competing.

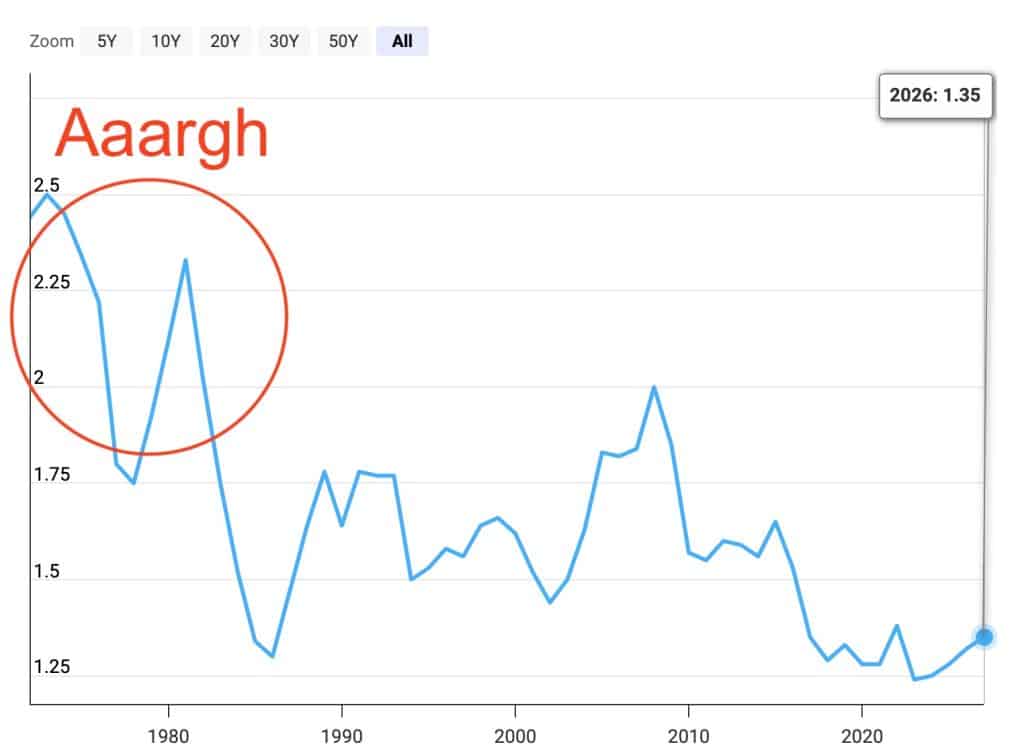

Things got worse with the rising British Pound. For the last 10 years, the GBPUSD has been around the 1.2-1.4 mark. But it was spiking in the early 1970s, spending a lot of time above 2. That would make it hard for any UK manufacturer to compete.

Meriden Triumph’s decline isn’t its story alone. There have been many studies in general on the decline of British manufacturing. Some traits often mentioned not just of Triumph, but of other companies were a) centralised management, leading to ineffective, slow decision making (vs the modern multi-divisional form of companies, which was being used in Japan at the time), b) labour-intensive, inefficient production, and c) wide product ranges with incompatible components. These were the main pillars John Bloor attacked in his reinvention of the brand.

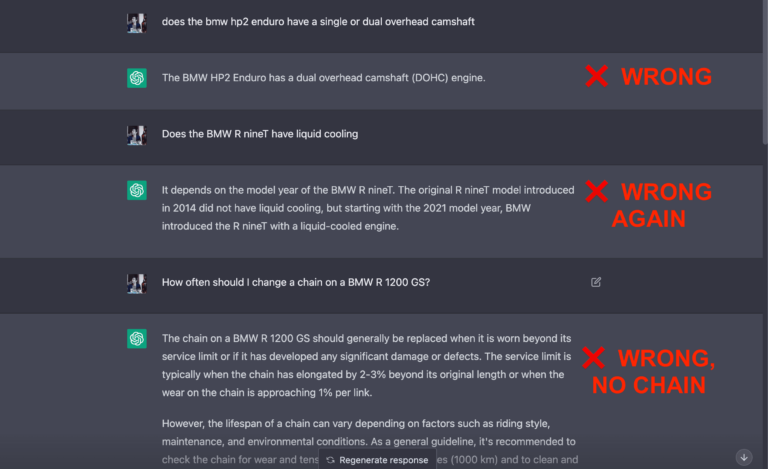

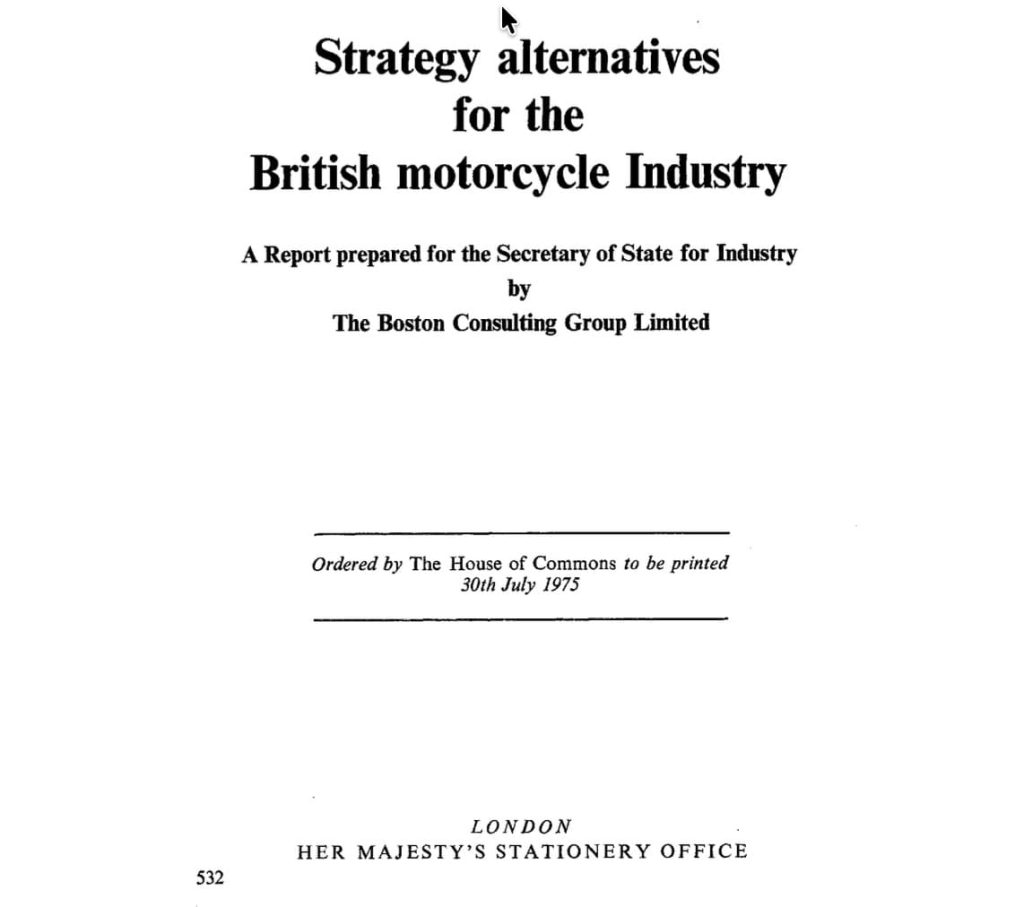

I don’t want to get all “I used to be a strategy consultant and make charts about how other people could make money” on you, but I don’t even have to, because Boston Consulting Group already did.

For those of you who’ve led fulfilling lives, Boston Consulting Group is one of the trinity of consulting firms (McKinsey, BCG, and Bain) that get paid a lot of money to tell you stuff that you kind of suspected, in chart form.

In this case, the BCG report showed that the Japanese didn’t initially attack the big-bike, prestige segment where Triumph lives, and used small bikes as loss leaders to build scale, distribution, and learning curves. It was a strategic play to capture the market.

The fundamental error that British manufacturers made was to give up small-displacement motorcycles, just as Japan was using them to build dominance. The British abandoned them because they weren’t profitable; the Japanese used them to capture market and mind share.

The report went in great detail to essentially say that Triumph lost because it tried to defend prestige while Japan built markets. Triumph (and BSA) focused on making bikes that were highly tuned, individually clever, but hard to standardise and difficult to produce automatically. These were expensive to make and couldn’t be made in high enough volumes. This, coupled with the fact that British manufacturers focused on the top end, meant that they just couldn’t build dealer networks and loyal customer bases like Japanese manufacturers could.

British manufacturers also dismissed the threat of Japanese competition — but this was at their peril. As nice as it is to have the option of a motorcycle entirely hand-built in the UK (almost impossible to imagine today!), it just wasn’t the option most people would take.

By August 1983, the original Triumph Motorcycles, which last existed in the form of the worker’s cooperative Triumph Motorcycles (Meriden) Limited, was bankrupt and wound down.

Phase 3: John Bloor, the Hinckley Era

Now we begin the era of Triumphs as most people know them.

In 1983, a British entrepreneur named John Bloor bought the rights to the Triumph brand name for pennies on the dollar. He hatched a plan not to continue the brand, or even to revitalise it — but to reinvent it.

Bloor didn’t buy a functioning motorcycle manufacturer. He mostly had intellectual property (brands, patents etc.). Bloor hadn’t acquired the factories, and the tooling was obsolete and out of date, anyway.

So from 1983 to 1985, Bloor did research. After buying the name in January 1983, he took a team of people to Japan in June of the same year. By September, they had scrapped everything, starting afresh.

In the subsequent years, Bloor and his team tore down Japanese bikes from Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki, and Suzuki, understanding production standards and what it would take to build vehicles efficiently.

Bloor built Triumph up again from scratch. He invested heavily in building state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities in Hinckley, Leicestershire (England), with CNC machining, robotics, and modern QA systems. His priority was to build modern motorcycles first, and then to layer the Triumph branding, heritage, and legacy on top.

Bloor’s team’s plan for motorcycles was to optimise production, using modular components: shared crankcases, common internal architecture, scalable engines, and a shared factory line. This helped Triumph get back in production quickly with a full production line.

In the late 1980s Triumph started running prototypes and test machines, but nothing retro. When the brand finally relaunched in 1991, it didn’t debut with a hero bike — it launched six models across three engine sizes — but all with liquid-cooled, three-cylinder engines.

- The Trident 750/900 (three-cylinder standard bikes)

- Daytona 750/900 – sport touring

- Trophy 900/1200 – big, plush tourers

- Tiger 900 — one of the early “adventure sport” bikes

- Thunderbird 900 — an upright, traditional triple

Early Hinckley Triumphs weren’t retro at all. They were modular, multi-cylinder bikes that were designed to compete directly with Japanese manufacturers on reliability and performance.

Triumph retired most of these bikes in the late 90s, but in the meantime had introduced the Speed Triple, the modern Daytona T595 / 955i (with fuel injection!), and the Sprint ST. These brands lasted a lot longer (though the Daytona is a little bike, these days).

Triumph’s reintroduction of retro models really started in 2001 when they introduced the Bonneville 790, which eventually became the 865 and now the T100.

This was the first bike that blended modern tech with vintage looks. I mean, the 790 was still air/oil-cooled and carburettor-fed. But it was a modern bike, built to be reliable, with an oil cooler and twin overhead camshafts. Thus began Triumph’s success with modern vintage bikes — motorcycles like the Speed Twin, the Thruxton, and the Bonneville, that have coexisted alongside their high-tech, high-power bikes like the Speed Triple, the Tiger, and the Street Triple (one of my favourites).

The rest is relatively recent history that is easier for most people to look up. The Scrambler came soon afterwards, and modern Triumph made all the motorcycles that we have today.

As an interesting addendum, Triumph has just recently begun to go back into small-displacement motorcycles with models in the Triumph 400 range. Maybe this is to ward off what looks like increasing competition from China — if so, they’ve learned their lesson!

Wrap Up — Does It Matter?

My unsolicited opinion is that gatekeeping things isn’t cool.

I’m not really into vintage motorcycles. I mean, I do like bikes from a certain era, around the year 2000, when they had fuel injection but weren’t all quiet and muted. But that’s purely a personal preference. Some prefer carburettors. Some like two strokes. Different folks like… well, you know the saying I was about to butcher.

Yes, modern Triumph is leaning on its historical ties heavily for marketing. As they should! This is the intellectual property that Bloor bought — the right to use names like “Bonneville”, “Speed Twin”, and “Triumph” itself, which is the cornerstone of the brand. Without that, it would basically be another Chinese company making bikes that may be wonderful and work perfectly, but which don’t evoke any sense of emotion from you.

Like it or not, we humans are squishy blobs of goo who do silly things like attach importance to names. It’s cool to think that the motorcycle we’re riding is somehow connected to Steve McQueen or Marlon Brando. Those of us who are of a certain age grew up hearing about brands like Triumph, Ducati, Honda and so forth, and even if you think you’re above brands, you only think so because you know brands exist.

So, first and foremost, it doesn’t matter that modern Triumph is different from the past generations of Triumph that preceded it. So be it. Those motorcycles were good for their day, and it’s nice to ride a descendant.

The second thing is that in many ways, modern bikes are vast improvements over the old. They don’t leak (they are super reliable — ask many mechanics!), they’re powerful, they sound great, and they’re easy to ride. I’ve loved the Triumphs I’ve ridden. This is the modern vs vintage dilemma that grips many traditionalists. Recently, I bought a 1996 Ducati Monster, thinking “This is all I need,” and guess what, it mostly just leaked oil and fuel and did my head in with carburettor woes until I sold it. My much more boring Triumph Tiger Sport 1050 never batted an eyelid, started every time, and did whatever it was told.

I also face the same dilemma with guitars. I see classic old Yamahas (I’m a sucker for Japanese guitars) and think “that’d be awesome”, but then when I play them, I realise they don’t sound or feel as good as modern axes that are half the price. I’m only mentioning it because it was an easier lesson to learn with a new hobby.

The final thing is that modern Triumph has been making motorcycles for over three decades now. A whole generation of young riders was born after John Bloor bought the brand. This might make some of you squirm, but for many, a 90s bike is a vintage bike! Yes, these are the same people who think of Pearl Jam, Nirvana, and my poison of choice, Rage Against The Machine, basically as classic rock.

So if someone gets in your face about your Bonnie or Thruxton not being the same Triumph as what they used to be, you can tell them it doesn’t matter. It’s still a great bike.