One of those terms that I see people discuss quite often is “unsprung mass”. I see the term “unsprung mass” in descriptions of

- Conventional vs upside-down forks

- Lighter wheels

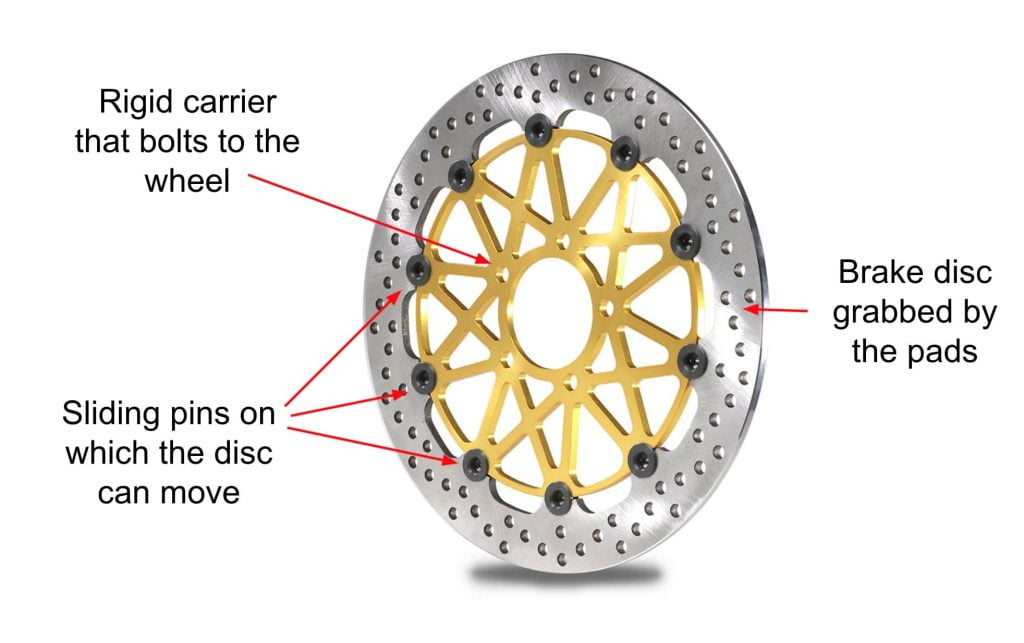

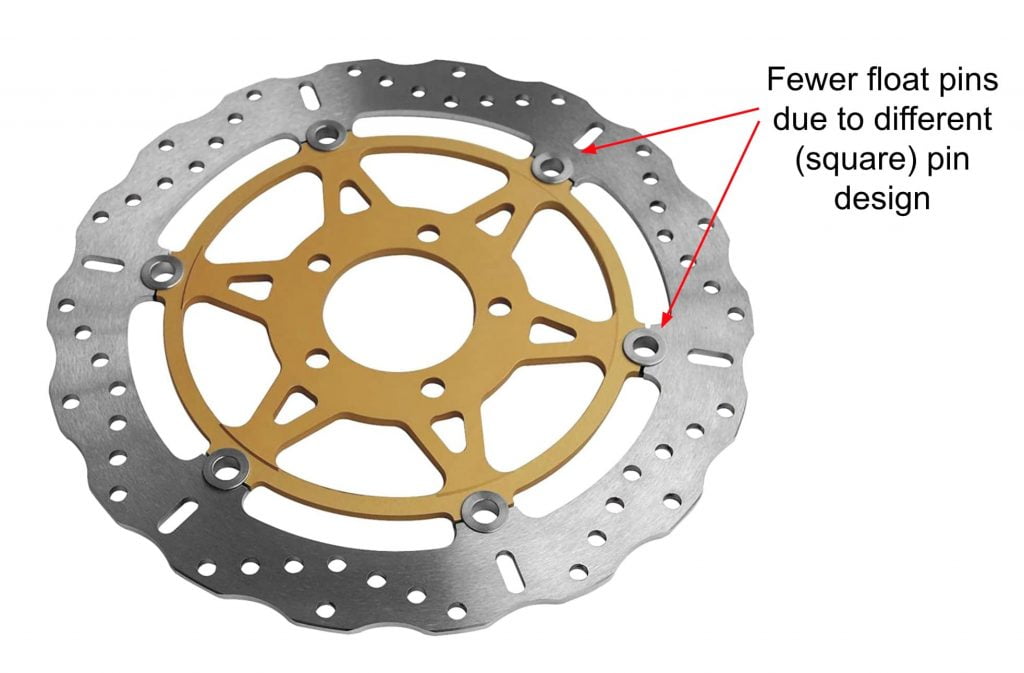

- Solid vs two-piece brake discs

- More advanced brake calipers

It’s intuitive to understand that a lighter bike will be easier to ride quickly. Less weight means higher power to weight ratio, less weight to tip into a corner, and an easier bike to pick up after I drop it (a brief apology to the bikes I have dropped).

But why is it better to have less unsprung mass? What even is unsprung mass anyway? And how do we reduce unsprung mass?

By the way, the term I’ll use is unsprung mass, not unsprung weight. In reality, we often talk about weight and mass interchangeably, and they’re usually the same thing, and I don’t like to be pedantic if we all understand each other. Weight is the application of gravity to a mass.

But unsprung mass has an effect whether it’s moving things up AND down, so there’s more than just gravity at play. It’s just that if you’re expecting the term “unsprung weight” — well, we’re talking about the same thing.

Here’s a bit of a deep dive into the topic.

See also — my deep dive into motorcycle forks.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

What is unsprung mass?

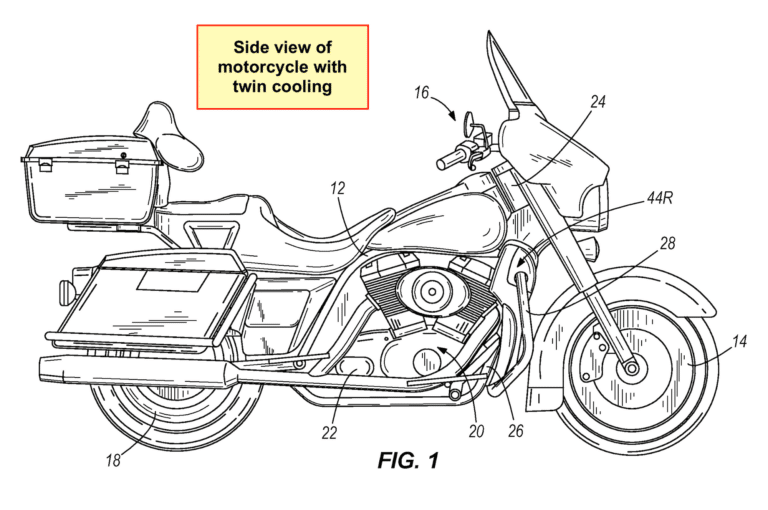

The “sprung” part of “unsprung” on a motorcycle (or bicycle or car) is everything below the suspension.

This includes the

- Bottom part of the suspension (the part that moves), whether it’s the stanchion or lower part of the fork or shock

- Wheel rim (on which the tyre sits)

- Tyre (compound, design, size)

- Brake disc mounted to the wheel

- Brake caliper

- Other bolts/bits/cables holding it all together

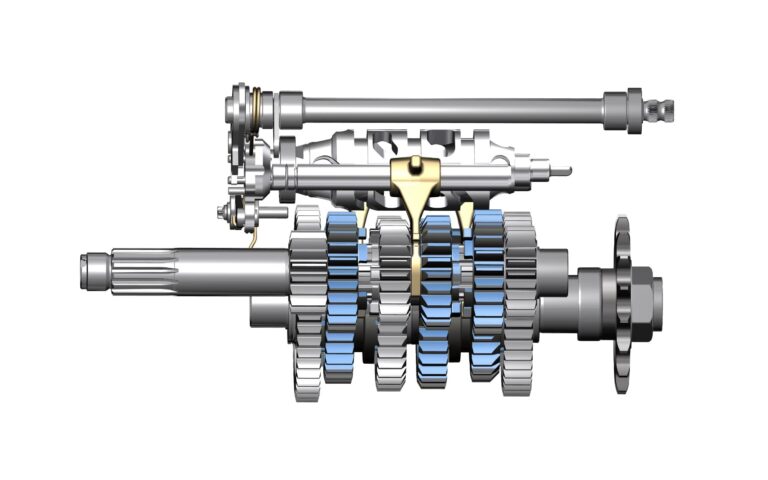

- Drivetrain components — Sprocket carrier + chain, or shaft drive

Every time you go over a bump, all of those parts have to move up. If they’re really heavy then it’s hard for them to change direction. The inertia of an object (its resistance to change in velocity) is proportional to its mass.

Because all those parts are below the spring, they all move together and form part of the same block of inertia. That’s why they’re all considered together.

On the front and rear wheels, different things have greater impact on unsprung mass.

On the front wheel, there is no drivetrain (well, not usually!), but the braking and suspension components are heavier.

On the rear wheel there’s just a shock and a little brake disc/single caliper, but there’s the rear half of the swing-arm, the bigger wheel, and the drivetrain components like the chain/belt + carrier, or the shaft drive.

The rear wheel has a lot more unsprung mass because of all these heavier parts.

Why is it better to have less unsprung mass?

Imagine riding over a series of bumps (and troughs). Every time you go over one the wheel and all the bits attached have to go up and then down, while hopefully you, the rider (and the rest of the bike) aren’t shaken to bits.

Each of these movements up and down of the wheel is a change in direction for the wheel and all moving unsprung components.

You can also see how hard it is to change direction of a heavy object by first doing ten push-ups as fast as you can. Now do it with a 20 kg weight on your back. See how fast you can go!

So because the goal of suspension is to keep the wheel in contact with the road, we want to make sure it can move as quickly as possible. The lower the unsprung mass, the faster the suspension can react to changes in road or traction conditions.

It’s the same reason they say that fast-running animals have tiny thin legs — so they can move them up and down quickly.

This is also the reason why race vehicles get lightweight wheels (like the Marchesini wheels on my Ducati 1098S). Less unsprung mass.

“But the difference must be marginal!” you cry, looking at two generations of CBR600RR side-by-side. The below pics are of a more recent CBR600RR on the left, with USD forks, and an original model on the right, with right-side-up conventional forks.

Both of those are sportbikes and both go very quickly. So what’s the deal — why did Honda change to upside-down forks?

The difference in suspension responsiveness of upside-down vs conventional motorcycle forks may indeed be minimal unless you’re on a bumpy road, really sensitive and/or pushing it — but it’s there nonetheless, in at least a pure physics sense.

Changing the unsprung mass of the rear wheel — has more significant impact. Looking at it another way, adjusting the suspension of the rear wheel or improving the rear shocks has a huge impact on ride comfort — much more than adjusting or improving the front suspension.

As I mentioned above, the rear wheel has much more unsprung mass. There’s the heavy swing-arm, the bigger wheel and tyre, and the drivetrain components. These more than outweigh the smaller braking and suspension components.

How do you reduce unsprung mass?

Might seem obvious at this point, but here are the most common ways in which people reduce unsprung mass on motorcycles.

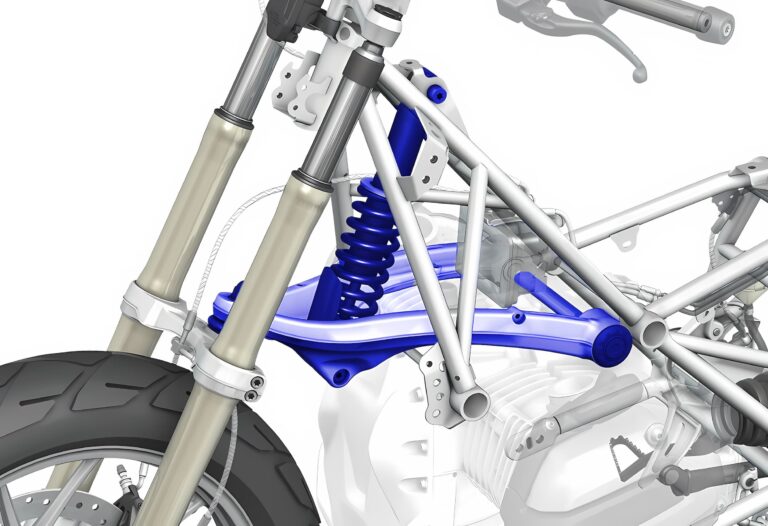

- Upside-down forks (or higher-end suspension). Conventional forks have the fork tube (or stanchion) at the top, affixed to the triple clamp. Upside-down forks are inverted, with the tube at the bottom. This has other benefits (more rigidity), but in this case the advantage is that the tube is the lighter part of the front wheel suspension, so having them at the bottom means less unsprung mass. Higher-end suspension is also designed to weigh less.

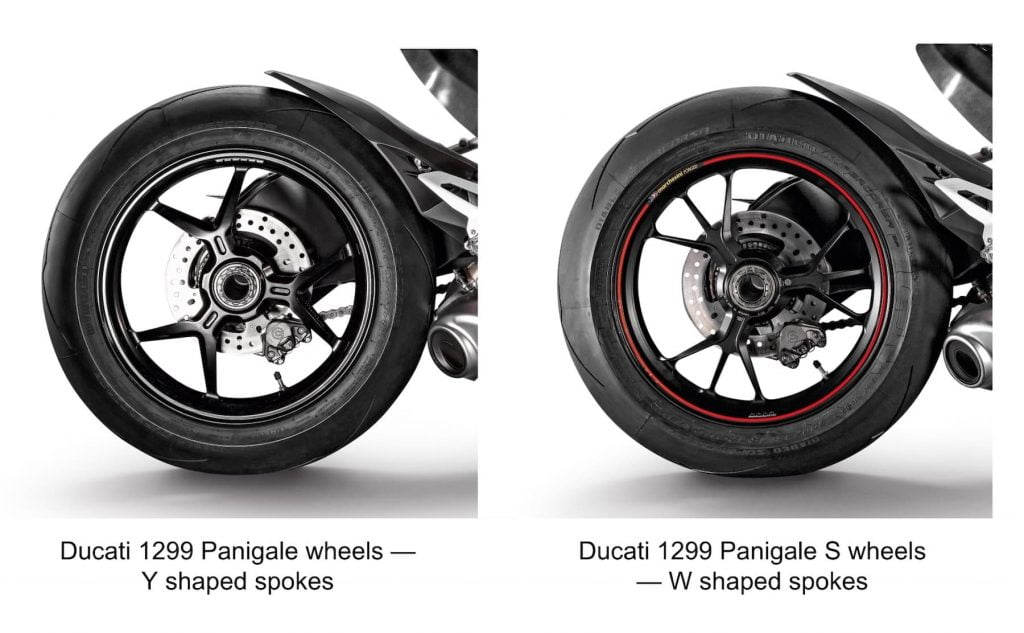

- Lighter wheels. High end sportbikes often have forged alloy wheels which are lighter. Between variants of superbikes, there’s often a more advanced version with lighter wheels — e.g. the carbon fiber wheel of the super-exclusive Honda CBR1000RR-R SP above, or the difference between the two Ducati 1299 Panigale wheel versions below.

- Lighter braking components. As braking technology got more advanced, manufacturers worked out how to keep (or increase) braking pressure and feel with lighter components. Some examples of this are monoblock calipers, which are made out of one piece of metal, and thus need fewer bolts holding them together.

- Lighter tyres. This is one I see discussed less often, but as tyre technology improves (or gets more expensive), you can get similar tyre performance with lighter tyres.

Manufacturers and owners have been doing some tricky things like changing the axles to larger diameter, hollow ones, fixing the brake discs to the wheel spokes (rather than to a center carrier), or reducing the number of pins on a brake disc.

In the image below, an improved design of float pins on the EBC rotor means that the brake rotor needs fewer of them for comparable (presumably) rigidity.

You can also make some design compromises when reducing unsprung mass — e.g. opt for braking that’s just not as good.

What are some compromises when reducing unsprung mass?

There are always design compromises when reducing unsprung mass.

Upside-down forks are typically more expensive, but they’re becoming very common on motorcycles — even some midrange or non-sport motorcycles (like the Suzuki M109R) have upside-down forks.

There are a couple of design compromises in upside down forks. These are that

- It’s hard to change the fork fluid. You ahve to remove the forks from the bike. And

- If you blow a fork seal, you can say goodbye to all the fork fluid.

Apart from that, they’re generally a good thing!

Another design compromise relevant to suspension is thinner, lightweight components. You lose a bit of rigidity as they get thinner.

Thirdly, one can opt for smaller tyres. These are lighter, but come at the cost of a smaller contact patch, all other things being equal.

Fourth, the lighter your wheels, the weaker they’re likely to be — or the more expensive. Wheels made of lightweight components are more prone to being dented or to breaking.

Fifth, on the rear wheel, you can use lighter drivetrain components. It’s one reason why you might opt for a chain-driven motorcycle rather than a shaft-driven bike, or why you might get a lighter chain and sprocket carrier.

Finally, you can always choose to have less effective braking to save precious grams on the wheels.

Sum up

There’s more to unsprung mass than just the above. But hopefully that was a good introduction.

There is also another benefit to reducing the weight of components around the wheel — less rotational inertia, which means acceleration and turning are both quicker. I will explore that at a later date.

Hi Dana, I`m a bit like you but older… Have been riding now for 57 years, been working on bikes for that long also. Ridden around and through Australia a number of times as I live here, started so called adventure riding on Yamaha XT500 with long range tank in 78. Also did from Michegan to LA in USA 94, but the best was from Durban to Israel back in 87 /88, 14 months for that trip

I lost count on bikes I`ve had, but probably round 130, mostly dirt/adventure bikes

Nowadays I mainly have BMW airheads with some other old dirt /adventure bikes as well

Like you, I like learning, an old guy once told me many years ago `the day you stop learning is the day you die`

Im coming up to 68yrs young soon and still love adventure riding, going out to Birdsville later this year, last year was out to Finke desert race (I did`nt race…….. just spectated as I don`t bounce so well these days) and where I live is a great area for adventure riding

I found your article on un sprung mass (weight) straight to the point and easy to understand, some articles I read these days guys think they are professors and waffle on with a whole lot of sh..

Keep up the good work

Cheers Rod

Thanks, I do try to keep it brief. Really appreciate your comment.

130 bikes!

Would love to cross paths one day in Queensland (where my family is) or Vic (where I am).

I’m stupid old at 76, however, there are motorcycle things one can still do. SCTA at ElMo last week 101.3. Sprocket change and looking for 108. It’s 96cc on Alcohol. If I pull this off I’ll be to Bonneville and maybe the AU next year. Nitro here we come!

You’re not stupid old. That’s wisdom right there. Well, my kind of wisdom…