For over a decade now, we’ve been lucky to have the Yamaha CP3 motor grace our motorcycle showrooms and take a coveted place in our hearts.

The CP3 — or “crossplane 3” — motor is a liquid-cooled, dual overhead camshaft three-cylinder motor (or “triple”) with an even firing order (240 degrees between each spark) that has always been “around 900 cc” and produced around 110-120 hp at peak. You know it from the FZ-09, MT-09, XSR900, Tracer 9… and more motorcycles!

There are relatively few engines that are instant classics like the CP3. There’s nothing quite like it on the market today — the Triumph Speed Triple is bigger and more performance-focused, the Street Triple smaller and higher revving, and the MV Agusta is in the “don’t point at it… don’t even look at it” category. Triples are only made by a few manufacturers, and relatively rare compared to twins and fours, and the CP3 is one that has been praised since launch, earning accolades from riders and press alike.

The Yamaha CP3 engine is my favourite engine. I mean, it’s the engine in my favourite motorcycles. The ones that feel like a cheat code for riding, that make me feel like I can do no wrong. I’m a sucker for Yamaha in general… I have a whole bunch of Yamaha music gear on my desk in front of me as I write this. But my love affair with Yamaha started with two wheels!

So, below is everything you might want to know about the Yamaha CP3, including a brief history of how we got here, a technical overview of the engine, how it changed, and models in which you’ll find it.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

The XS Line (1976-1981) — The First Yamaha Triples

Yamaha first brought us the CP3 in 2014 in the FZ-09. But it wasn’t their first triple. In fact, they had done triples on and off for decades, though off for an extended period.

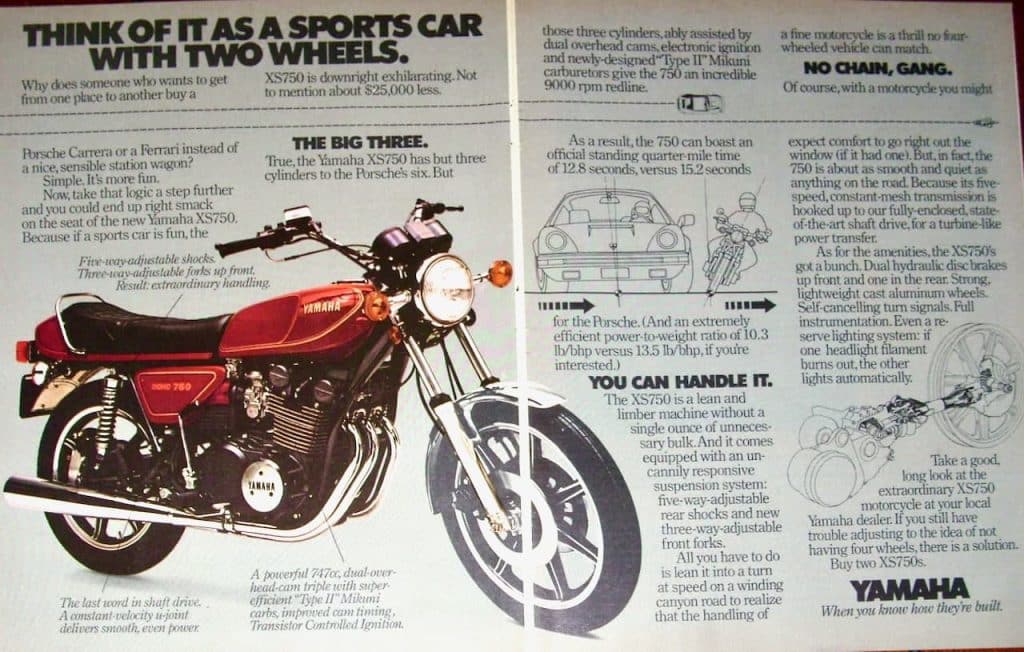

Yamaha’s experiments with triples started in the 1970s with the Yamaha XS750.

The 70s were a heady time for Japanese motorcycle manufacturers. They were just coming into the limelight, with the Honda CB750 having helped usher them into widespread acceptance.

The XS750 was introduced in the 1976 model year (announced at the 1975 Las Vegas Motorcycle Show) as an alternative to four-cylinder bikes (Honda CB750) or other 750s (Kawasaki Z750) being put out by other manufacturers. The XS750 had a 747 cc air-cooled DOHC engine, and just to spice things up a little more, a shaft drive!

The first gen XS750 had single disc brakes front and rear (the one pictured above has dual discs), seven-spoke rims (which was a relatively new way of styling wheels at the time), and a few interesting innovations, including floating single-piston calipers and even self-cancelling turn signals.

But the important choice that Yamaha made was to space the firing equally around the crankshaft, 120 degrees between each. This means that there’s no stop-start that you even get in most four-cylinder engines, nor in some three-cylinders (both past and present) that opt for uneven firing intervals. The parts are always in motion. This design gave the XS750 a feel that was entirely unique at the time. (It’s also a design that Yamaha continued to today in the CP3 engine.)

Yamaha kept building the XS750, iterating on components, adding twin disc brakes, a 3-into-two exhaust, adding power (upping the compression ratio from a mild 8.5:1 to 9.5:1 in 1978, though lowering in 1979 to 9.2:1), tuning the bike more for touring, and adding some cosmetic enhancements.

While Yamaha launched the XS750 as a sporty tourer, it evolved to become more and more of a tourer. Yamaha did this by raising suspension, raising the bars, and changing the gearing. It was never a straight line or cornering demon, but it was comfy out on the open road.

The XS was an interesting bike and it’s an iconic collector classic. But it’s not perfect.

One downside was the shaft drive. I’m a fan of shaft drives, to be fair, even though they have a weight and power delivery penalty. But the XS’ early shaft drive suffered from one that many early shaft drives did: torque reaction. I explain this more in the article on BMW Paralever, but it’s essentially this: Under acceleration, the twisting motion of the shaft drive creates a torque reaction that pushes the chassis up and pushes the rear wheel down. This increases traction but it changes the bike’s geometry in a weird way, rising rather than squatting under power.

Another quirk of the gearbox of the XS models. They were known to be clunky, especially when cold, and especially when shifting into first.

In general, it was acknowledged that the XS750 wasn’t the fastest, nor the best handling, nor even the smoothest 750 made, but it was definitely interesting!

Yamaha kept building the XS into the 80s, increasing it to 826 cc in the XS850 in 1980.

Yamaha didn’t change much apart from the motor, which was a welcome change (and welcome lack of change) among fans. They increased the bore from 68 mm to 71.5 mm, kept the 9.2:1 compression ratio of 1979, and changed the combustion chamber and valve timing. Yamaha also changed the carburettors from Mikuni (used in the 750) to Hitachi CVs.

Yamaha also improved the smoothness of the drive shaft on the XS850. Cycle World put the class leader as the Suzuki GS850 at the time; they described the Yamaha XS850 as “as close as they can to the standard set by Suzuki.” However, they never did quite solve the shifting clunk or play in the line. Not that it really matters. These bikes are old. Clunking is part of the game.

Yamaha retired the XS850 after 1981, pivoting to other formats to meet competition.

The Interim (1982-2013) — What Did Yamaha Do?

Strange question, but many of you might be wondering: What were all the distractions and diversions that Yamaha had before finding its way back to the triple?

The short answer is inline fours, parallel twins, V-twins, and even V-fours. Plus singles. Anything else I’m missing? I think that’s it. But mostly, inline fours. First air-cooled, then both air- and liquid-cooled, and finally, just liquid-cooled.

Seriously, there are too many “interim motorcycles” to list. Inline-four-powered superbikes and tourers, a V4-powered cruiser, parallel twin road bikes, air-cooled inline-four muscle bikes, single-cylinder adventure, dirt, and trail bikes, and many more.

Yamaha created countless icons which are still classics today, including the YZF-R6 and YZF-R1 (no longer in street-legal production in most parts of the world, but which captured the imaginations of many riders for decades), the first Ténérés which gave rise to their modern incarnations, all the Virago and V-Star cruisers, and historic classics like the VMAX, a big bruiser of a V4-powered muscle cruiser that has had few direct parallels.

The point is Yamaha wasn’t exactly asleep at the wheel. It was experimenting, iterating, and adapting to the market.

By the early 2010s, Yamaha banked on two trends. First, the era of ever-larger, ever-heavier inline-fours was losing steam on the street. Second, their work on the crossplane crank in MotoGP and the YZF-R1 (buyer’s guide) had fundamentally changed how Yamaha thought about engine character.

So, instead of pursuing ever more power, Yamaha went down the path of understanding how to better deliver everyday torque.

At the time, Triumph’s major line of naked bikes was the FZ series. There were various capacities, based on earlier generations of the R1 and R6 engines, but the most recent ones were the FZ1 and FZ8, both based on the R1 engine (but the FZ8’s was sleeved, with new internal components).

The FZ1 and FZ8 were based on the older, pre-crossplane YZF-R1. In 2009, Yamaha had debuted the “CP4” engine in the R1 — the first time they had used the “Crossplane” moniker.

In the R1, Crossplane meant something significant. It meant a distinct firing order from every other R1 on the market that made a) traction in a different way, and b) a very cool sound.

To this day, those early crossplane R1s are iconic bikes. Nothing sounds quite like them. I think they’ll be collector’s items, even though I don’t think there’s a good business case for collecting bikes. The engine became an instant classic, and suddenly Yamaha had an opportunity on its hands: to bring the crossplane concept to other formats, like triples and twins. The story of twins is the story of the CP2, another instant classic engine that is as awesome today as it was when it launched in the FZ-07, but we’re talking about the CP3. I’ll get to it in a second.

I think it’s also important to note that a couple of other manufacturers were still producing triples en masse — particularly Triumph.

Triumph had been building its Speed Triple since 1994 to almost no competition.

Triumph had also built other triples on the same platform, including the Tiger, the Sprint, and other variants. Plus, Triumph built other triples, both larger (the Rocket) and smaller (the Street Triple). Three-cylinder bikes is their thing.

The only other significant maker of triples was MV Agusta, who make great engines, and bikes that are very easy on the eye, which are unfortunately out of the price range of most riders. Other factors, like relative scarcity and lack of dealer support, make them a less common choice.

Yamaha CP3 Motor (2014+) — Technical Overview & Generations

After over three decades of hiatus, Yamaha found its way back to inline three-cylinder motors with the 2014 MT-09, known as the FZ-09 initially.

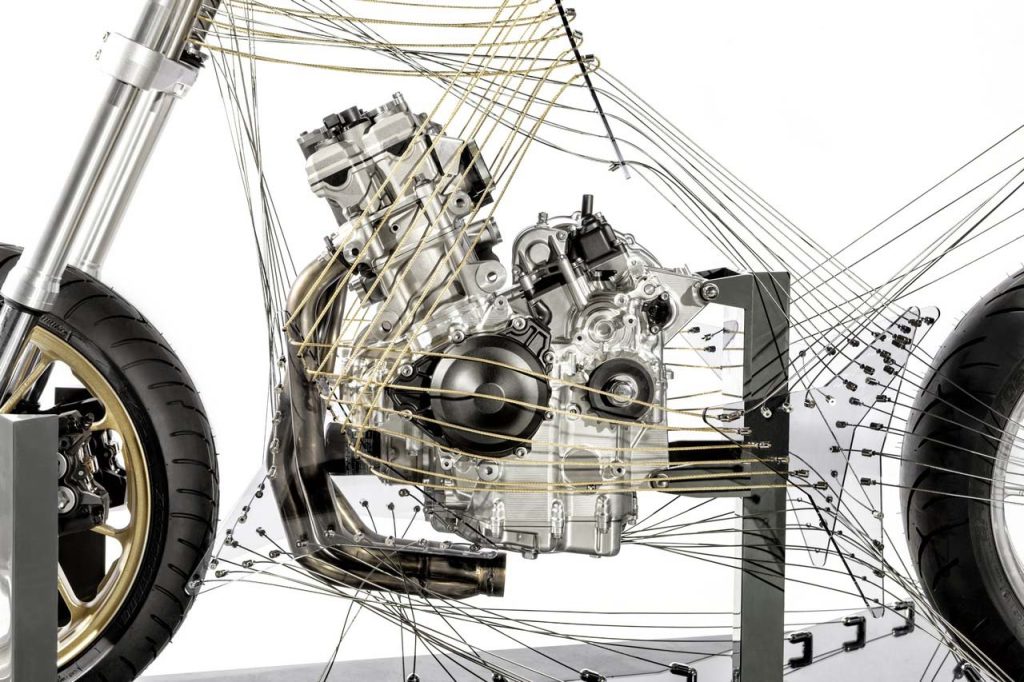

Yamaha first teased the idea for the CP3 motor publicly at the Intermot show in Germany in 2012, where they displayed something that barely qualified as a motorcycle. Suspended between two wheels was a compact three-cylinder engine, which, according to Yamaha, was a new engine concept that would “open up new horizons in riding enjoyment.”

The stated goal of the concept was the same one Yamaha had chased with the R1 and M1: eliminate inertial torque. Inertial torque is the unwanted resistance created by accelerating and decelerating heavy engine components. Even if combustion torque is smooth, inertia torque can make power delivery feel jagged or vague.

To eliminate (or reduce) inertial torque, the cleanest way to do this is to space the crankpins evenly. This is easiest in a three-cylinder engine, in which you can space the firing intervals exactly 120 degrees apart.

Nothing new here, of course. Yamaha had made 120-degree firing order triples in the past, as had other manufacturers before and since. Modern (John Bloor-era) Triumph had been making triples for over two decades, though they would, later, start experimenting with different firing orders (“T-Plane”).

That even 120-degree firing order layout balances the secondary inertia forces naturally and produces an even firing order. What remains is a primary rocking couple.

“What’s a rocking couple??” you cry, understandably. (I did!) A couple, in physics terms, is two forces acting in opposite directions but not in the same line, creating rotation instead of lateral movement. In an engine’s rocking couple, one end of the engine is pushed up, and the other end is pushed down, which leads to a rocking motion.

In the CP3 motor, even though the pistons are evenly spaced, they’re still all in a line — they’re not symmetrically arranged around the engine. So they’re putting pressure on different ends of the engine at once.

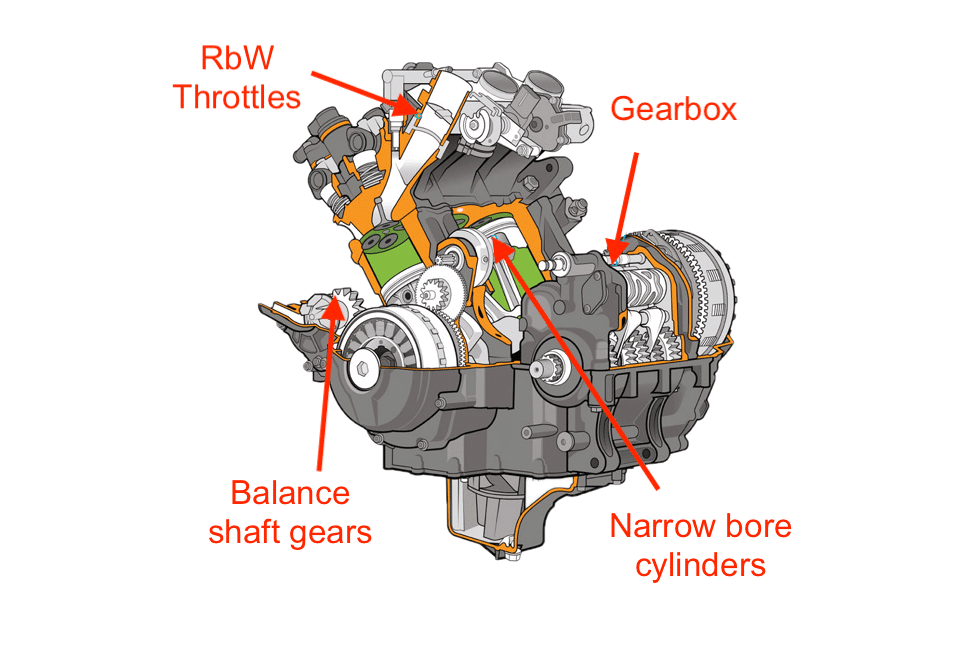

Yamaha solves the rocking couple in the CP3 with a gear-driven balance shaft. This spins at the same speed as the crank in the opposite direction, producing an opposite rocking force. This cancels the rocking motion out, dramatically reducing vibration.

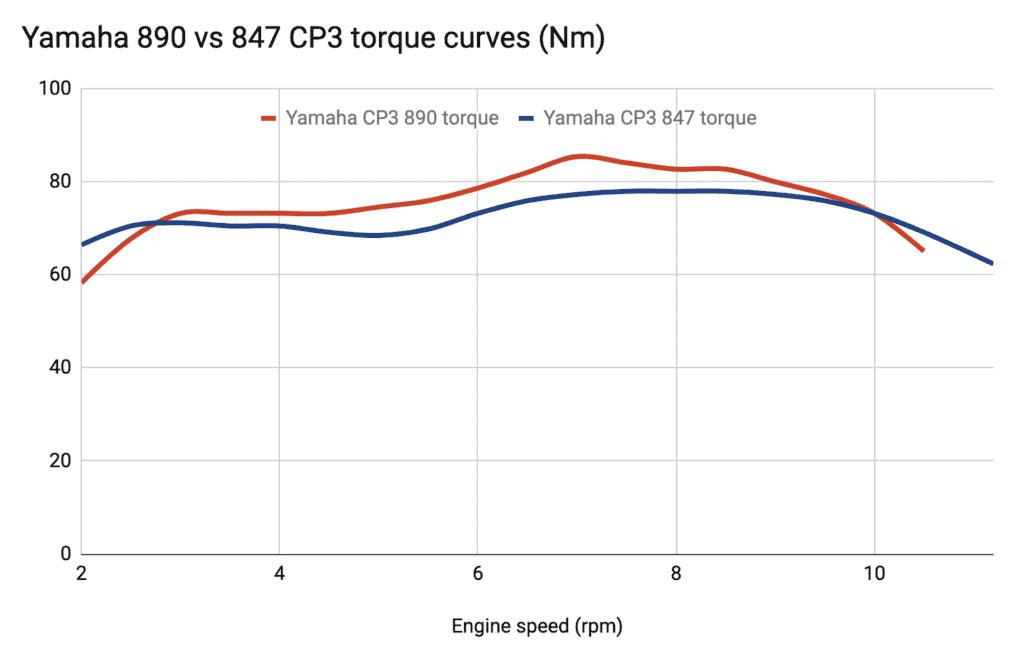

So the net result is a very smooth, torque-rich, but still rev-happy engine — that should make everyone happy. If you’re not convinced, look at the below torque curve, a superimposed chart of the 847 and 890 engines.

One question that’s on many people’s minds is “How is the CP3 ‘crossplane’? It seems like the most un-crossplane design I can think of,” and your instincts are right. Yamaha originally used “crossplane” to refer to the CP4’s uneven firing interval, but for the CP3, they evolved their definition to mean “clean, predictable torque by counterbalancing secondary inertia sources.” Calling the CP3 that is marketing speak that capitalised on the CP4’s popularity, not a description of a technical design.

Another interesting choice Yamaha made was not to give the CP3’s pistons dramatic dimensions. In a world of ever-increasingly oversquare engines, the Yamaha FZ-09’s original CP3 had a relatively tame bore:stroke ratio of 1.32:1.

Kevin Cameron explains this well in Cycle World. He says that the only reason sport bikes have giant bores (and thus high bore:stroke ratios) is that they need large valves that flow best at the top end. But this creates a difficulty of even combustion and breathing problems at the mid range and low end, which is where street riding normally takes place. Thus, Yamaha gave the FZ-09 a smaller bore and smaller valves, to prioritise mid-range performance.

The original CP3 motor was, and remains fantastic, but it wasn’t perfect. It was described as snatchy, particularly in the difficult-to-tame chassis of the original FZ-09. The core problem was fuelling, but it was exacerbated by the FZ-09’s soft suspension, and not helped by the fact that the bike was — usually not a problem — so light! So many riders of the original FZ-09/MT-09 said they could only ride it in “B” mode, which was an unsatisfactory compromise (why would you buy a bike with multiple power modes when you can only ride it in one mode?)

Evolution of the CP3

Over the years, Yamaha tamed the CP3 engine’s fuelling and correspondingly improved the suspension of the bikes in which it went. The XSR900 was easier to pilot, as was the FJ-09 (now known as the Tracer).

Yamaha also released the MT-09SP, which had high-end Öhlins suspension. This, too, helped rein in the snatchy (though improving) fuelling.

But the next gen of the CP3 solved the problem at its core.

Yamaha increased displacement to 889 (or is it 890?) cc for the 2021 model year of the MT-09. Other models (Tracer 9, XSR900, etc.) soon followed suit.

It seems like a minor change, but there’s little interchangeability of parts between the new and old motors. The pistons, connecting rods, camshafts, and crankcases are all new, resulting in a more torque-rich, powerful, and lighter (by 1.7 kg or around 3 lbs) engine.

Yamaha focused on getting this second-generation CP3 right. They fixed the fuelling! Rather than jack up the power, Yamaha used the extra 43 cc of displacement to boost midrange torque, and they tuned the engine not to suck the most power possible out of 890 cc, but to make for a predictable ride.

| Item | First gen CP3 | 2nd gen CP3 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years | 2014-2021 (MT-09) | 2021+ (MT-09) | 2022+ on the XSR900, 2025+ on YZF-R1 |

| Capacity | 847 cc | 890 cc | Some sources say 889; bore and stroke calculates to 890 (see formulas page) |

| Bore / Stroke | 78 x 59.1 mm | 78 x 62.1 | Slightly longer stroke |

| Compression ratio | 11.5:1 | 11.5:1 | Same, surprisingly |

| Peak power | 84.6 kW / 115 PS / 113 bhp @ 10000 rpm | 87.5 kW / 119 PS / 117 hp @ 10000 rpm | Bit more |

| Peak torque | 87.5 Nm / 64.5 lb-ft @ 8500 rpm | 69 lb-ft / 93 Nm @ 7000 rpm | More torque, lower down |

| Peak RPM | 11300 rpm | 10600 rpm | Per various sources (Ivan’s performance, dyno readings) |

It really worked. I swoon thinking of the good times I’ve had riding the 2021 Yamaha MT-09SP (here’s my review). A stark contrast to the early FZ-09, which was fun, but just not the same.

You might notice that the peak RPMs dropped. But in practice, this doesn’t really matter. The modern CP3 engine is one that’s so satisfying all the way between 3 and 9,000 rpm that it would be rare to send it to the top end. If that’s your game, maybe you’re looking for a different kind of bike.

Modern CP3 Models

These are all the motorcycles that Yamaha makes (or has made) with the CP3 motor. It started with the naked, but quickly evolved to the adventure bikes, the retro bikes, the three-wheelers (of course! Everyone saw this coming), and finally, the sport bike.

Yamaha FZ-09 / MT-09 / MT-09 SP

The FZ-09 is what started it all off. I give a full model history of the FZ-09 / MT-09 here.

The FZ-09, later renamed the MT-09 globally, is the naked bike. It’s light, responsive, and fun. The later incarnations (2021+) is all I’d ride — maybe the earlier SP, but even that looks a bit dated these days.

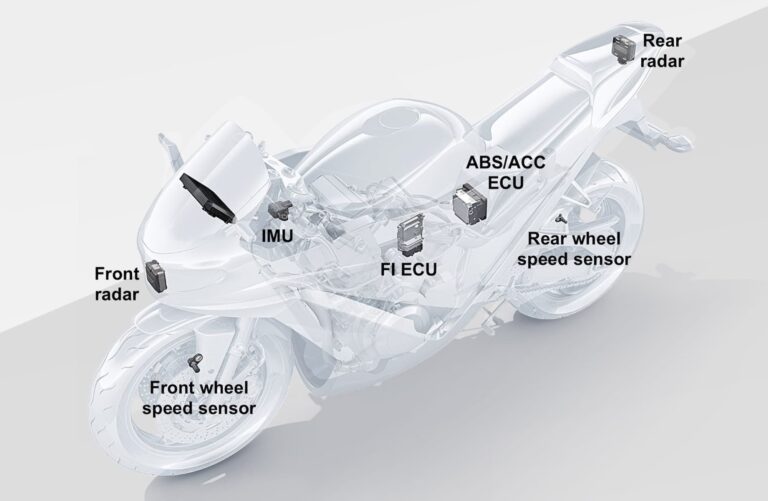

Yamaha has been generous with the MT-09, bringing innovations like an IMU and cruise control to it first — though I’m glad to see them make it to other bikes in the lineup.

Yamaha FJ-09 / Tracer 900 / Tracer 9

Second was the FJ-09, later renamed the Tracer 900, later the Tracer 9. See the full buyer’s guide here.

The FJ-09 / Tracer is the adventure sport tourer. It’s a bike that does a lot of things well, so much so, that it is a little boring. What I like about the Tracer is that it’s not as heavy as big sport adventure tourers. It’s basically the weight of most standard naked bikes! And it actually received a few tech touches before the MT-09, like cruise control.

Because the Tracer is heavier than the FZ-09, its power delivery is more predictable. In fact, I don’t recall it being difficult to ride at all, compared to the same-gen FZ-09/MT-09.

The Tracer is a popular police motorcycle in Europe, which says it all: it’s easy-mannered, incredibly reliable, fast, comfortable, and predictable. If you find joy in easy distance plus occasional twists of the throttle, you might like the Tracer.

Yamaha XSR900 / XSR900 GP

It’s a great day to be a hipster who likes motorcycles. Yamaha rejigged the MT-09 to look more like a classic café racer, and I love it.

The XSR900 is a modern retro. Not quite as stripped back as earlier air-cooled bikes, and to be fair, that exposed engine is kind of ugly. This is a functional retro. For all intents and purposes, it’s very similar to the MT-09. They share a frame and engine. The seating position and wheelbase are slightly different, so they feel a bit different, and it’s worth testing both. But really, most of the testing will be done by your eyeballs!

Still, I really like it, and think it has become only better looking as time has passed. I have a particular fondness for the special edition colours and the GP version with a bikini fairing. I’m shocked it’s not available in more countries, and equally shocked it’s not more popular. (Then again, I don’t have one, but we’re just spoiled for choice for bikes, aren’t we?)

Yamaha Niken

I have never seen a Niken in person and find it remarkable that people buy them. I completely understand the appeal, and the logic, but I just don’t see them.

It’s an MT-09 CP3 engine but in a motorcycle with three wheels. More traction up front means fewer crashes, but also fewer wheelies, if those are your thing. The Niken leans, is comfortable, and is apparently fun to ride, plus it’s definitely eye-catching.

Yamaha YZF-R9

Yamaha finally released the YZF-R9 in recent years, positioned between the Yamaha YZF-R1 and the YZF-R6, both of which have been retired from street-legal form in many markets. To me, this is the best of both worlds of the R1 and the R6, but for street use.

The R9 is, if it isn’t obvious, a fairing-equipped sport bike. Instant classic, especially in those 2026 SP colours! The R9 isn’t actually as committed a sport bike as the old R6, making it a great “everyday” sport bike, something we hadn’t seen much of since the 2000s.

Yamaha is giving the YZF-R9 the full treatment — quality suspension and brakes, and even cruise control, putting it in the same league as top-end bikes like the BMW S 1000 RR for everyday usage. I’d pick the Yamaha, but I am not the speed demon I was in my youth.

Wrap up

It’s truly a glorious time to be alive. I think the CP3 motor is one that will go down as one of the last great motorcycle engines while it lasts. It’s perfect for so many situations. It won’t last, of course — emissions will come for it. But it hasn’t succumbed to horsepower wars, and has remained focused on everyday performance, and considering the attention Yamaha has given bikes in which they’ve put the CP3, I think we’re all the better off for it.