I read “A Twist of the Wrist” by Keith Code, expecting it to be about motorcycling and motorcycle racing.

Instead, it turned out to be a book of life philosophy and advice to apply in business and life.

At the base of motorcycling, like any pursuit — mental, athletic, or artistic — is the human condition. The way we push through limits, learn from mistakes, and maintain the correct attitude is what separates champions (or just people who improve) from other riders.

Keith Code captures all of this in “A Twist of the Wrist”. Even though he presents it as a book about motorcycling, he writes like a philosopher. This is obvious from the first lesson: don’t badmouth yourself. Instead, focus on what you can improve.

Here’s my summary and notes from the book. They’re lessons about motorcycling, but they’re also about life.

Note: I broke up Keith Code’s paragraphs, which are too long. Also, in the quotes below, I changed “he” as a description of a rider to inclusive language. Most riders are men, but many of my favourite rider friends and instructors have been women.

You might also like my recommended books for learning how to become a better motorcycle rider.

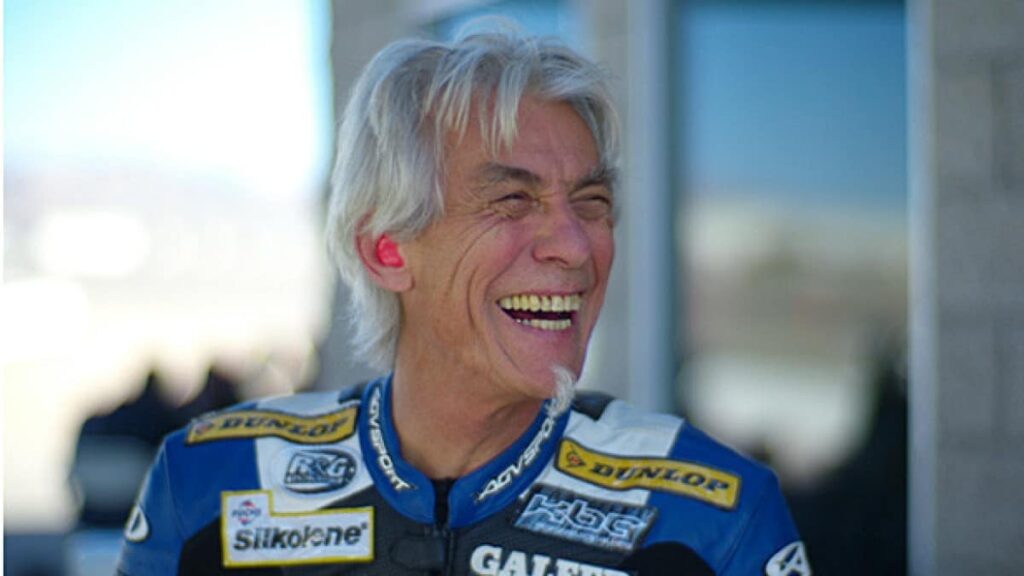

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

Don’t badmouth yourself. Reflect on what you can improve, not what you did wrong.

Keith talks about how we talk ourselves down in life. Riders have a bad habit of focusing on what they don’t do well, or how they screwed something up. This is just like many of us in life — over-weighting mistakes we made.

Instead, he advises, we should look at mistakes as opportunities to do things better. We should be focusing on what we can measure and improve.

Many riders have a bad habit of talking in negatives about their riding. “I didn’t go in hard enough,” “I should have gotten a better drive off the corner,” “I don’t use the brakes that well,” “I need to get a better line through this turn.” Didn’t. Can’t. Shouldn’t have. Don’t. Too much. Not enough.

Most riders use these negative words much too often. How can information about what the rider didn’t do right, or things that were almost — or not quite — done, ever improve their riding?

If a person is riding at all they are already doing more right than wrong. The job is to add to those correct actions and drop the incorrect.

Ride out mistakes, to learn the full lesson.

In racing, it’s tempting to try to correct a mistake right away. But this prevents us from learning the true consequences of our actions.

Because there’s margin for error on the track, Code says it’s instructive to “ride out” a mistake and see where it goes, so you can keep notes on the situation later, and learn a more comprehensive lesson.

You can easily cheat yourself out of the knowledge to be gained from mistakes.

Let’s say you got into a turn a little too hard and went wide of your line. Normally, you would try to get back to that good line — to what worked. That’s fine, but there’s a twist.

If you “ride out your mistake” you will learn how that different line works. Trying desperately to get back to the ideal once you’ve made a mistake won’t tell you anything except that you’ve made a mistake.

Riding out that mistake will give you valuable information about how to handle it should it ever happen again.

Similarly in life, this is analogous to running a full experiment through to its conclusion. If you start a project or a new hobby, don’t just bin it at the first sign of difficulty.

Do proper testing and understand what went wrong. You might otherwise miss out on learning something you could apply to the next initiative.

Look for the root of mistakes in the inputs, not the outcome.

Riders tend to focus on what went wrong, like “I didn’t turn soon enough”. But that’s just the last thing you did. Look for the inputs to the situation: how fast you were going, where you started braking, and so on.

The root of the mistake is the control change or the decisions you made and acted upon just before the problem occurred.

A good example of this is going into a turn too wide. You got there because it was where you pointed the bike the last time you made a steering change.

Most riders would say, “I didn’t turn soon enough.” That isn’t true. Actually, you kept it pointing straight too long.

It will take a lot longer for you to realize what happened by looking for the problem at the point where you noticed it rather than going back to the earlier point where you were steering before beginning the turn.

You have to realize that you were was operating from an earlier decision to go straight, not the later one to turn.

The way I take this as a life lesson is to try to understand the root cause of any thing that goes wrong. It’s unproductive if I focus on having failed — I have to try to understand why, and change that behaviour next time.

And if I can’t find the root cause, look earlier

Follow your own path.

Find your own path around the track, not somebody else’s. Everyone rides differently.

I asked a better rider to show me his “lines” around the course.

We went around the track at a good practice pace as I carefully observed what he was doing in hopes of finding out some deep, dark riding secrets. I did find out.

I found out that a rider’s line is his plan for going through a turn. His plan is based upon what he does well and what he doesn’t do well.

I observed, then and now, that a rider’s plan will be based upon his strengths and weaknesses. His line is the result of how his strengths and weaknesses fit together.

You can learn a lot from watching others. It’s probably important to follow others around while you’re a beginner. But ultimately, you need to learn about yourself.

The faster you’re going, the more aggressively you have to turn.

When you’re going faster, you have to turn differently: you enter differently, you brake differently and at different times, and you turn more aggressively.

If you make your major steering change at the same point going into a turn — and increase your speed past that point — you will run wide of the point you passed on the last lap because of the increase in centrifugal force.

If the bike runs a bit too wide at the exit, you may believe you went too fast. Actually, the remedy is to go later before making the steering change.

The faster you wish to go through a turn, the later you have to enter it to increase your speed at the exit.

What will change if you do this? If you go in later and faster, the steering change will need to be more abrupt and the bike will not want to turn as easily as before.

The trick to going in later is to go a bit slower right at the point where you make your steering change.

I’ve learned the same lesson in life over and over. In investments, I can’t keep making the same size investments I was making when I started out. As I do better professionally, the more aggressively and innovatively I have to market myself.

They sound like boring examples next to motorcycle racing, but I learned them anyway!

The best racers are those fastest at learning to read and interpret critical information.

Code in A Twist of the Wrist and track riders talk about “reference points” on a track.

You learn as many reference points as possible — they could be a sign, a marker, a bump, or even just a dark bit of road. You read them to know when to brake, when to accelerate, when to start leaning etc.

The best racers are those who learn the reference points and how to interpret them quickly.

A reference point is not merely something you can see easily on or near the track, the reference point must mean something to you when you see it.

Every time you pass or approach it, this point must communicate a message to you, like, “This is where I begin looking for my turn marker” or “If I’m to the right of this too much I’ll hit a bump but to the left of it I’m alright” or “This is where I begin my turn.”

Reference points are reminders of where you are or of what action you must take.

One factor that separates the top riders from the rest of the field is that they pick up RPs quickly and accurately to the point they can see the “whole scene” without having to pick out the individual RPs.

In the same way, doing well in life and in business is about reading signs and data, and doing so quickly, and more effectively than others.

Don’t watch others; watch the track.

This lesson from A Twist of the Wrist speaks for itself. Ride your own race!

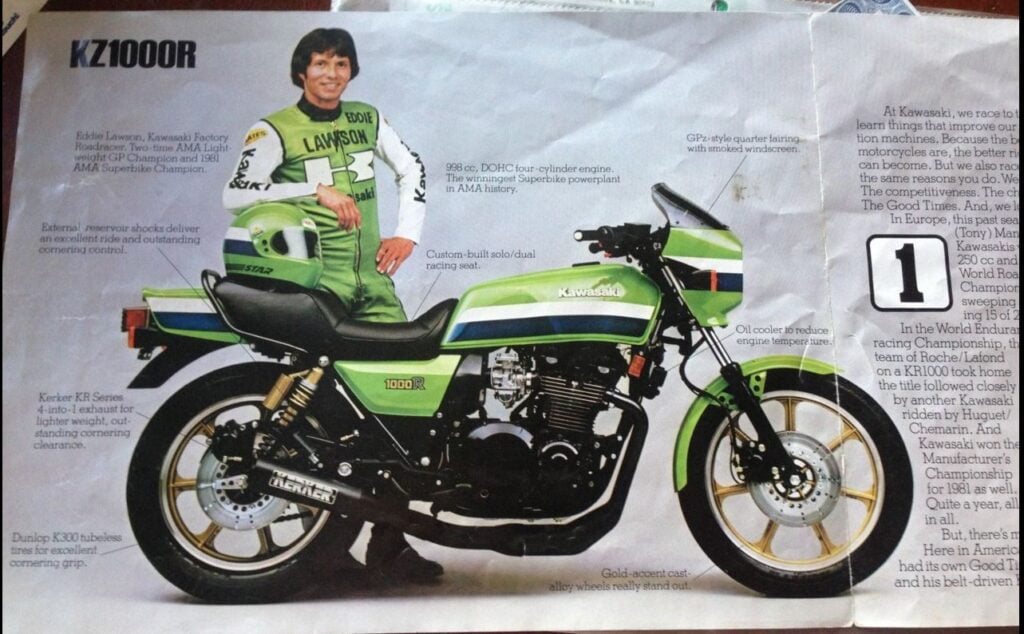

Code actually quotes Eddie Lawson.

“Guys get in trouble watching the rider in front. You’re aware that they’re there but you look at the track.” — E.L.

This advice can be counter-productive in reality. I mean, we have to know our markets, it would be silly to ignore the competition. But we can’t be obsessed by others, either.

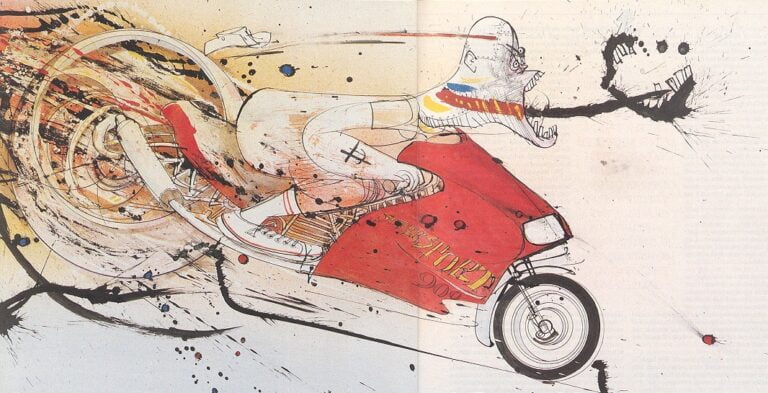

Who’s Eddie Lawson? He’s this guy.

First do it right, then add speed.

An old mantra of learning to do something right, and then going faster. Just like “before you run, you must learn to walk”.

Keith talks about this as the “decision to go faster” in A Twist of the Wrist, and how it has to come on the back of learning and experience.

Once you’ve gone through the boring parts of looking and experimenting to see what works, you are armed with enough knowledge to make your decision to go faster really work.

Without solving some of your barriers and rough spots on the track, you just make mistakes at a higher speed.

It has been said many times by many good riders: First do it right, then add the speed.

Same goes for one of my other hobbies, weightlifting — first do it right, then increase weight. And if I have bad form, do it with lighter weight until I improve my form, then go back up.

You gain more in the race by going faster in long sweeps, not tight turns.

People focus on the times when they’re going slowest — those tight, small corners. But the place where you gain the most is on the long sweeps and straights.

So one lesson in A Twist of the Wrist is: Don’t go fast around a slow corner only to not go as fast on the long sweep — it’s a net loss.

You gain more time in the fast turns than you do in slow ones. You will find, as every rider has, that a little faster in the fast turns makes much more difference than a little faster in the slow ones. You cover more distance in the fast turns, which brings up your overall average faster.

It’s easy to get obsessive about getting faster in the tight turns — that’s the technical stuff that is so much fun. But learning how to really get to top speed has the highest pay-off in terms of overall lap times.

The best riding advice comes from your best friend: You

Everyone has advice on the way you ride, but you have to know how to interpret it for yourself.

One word of advice about people giving you advice about your riding — you are your best advisor.

You’re the one sitting in the saddle and riding. No one has better information about what is going on in your head than you.

Deal with your own decisions, your barriers, your products and reference points, your points of timing and attention — not someone else’s.

The way your riding looks to someone beside the track has nothing to do with how you are thinking about it. In the end, you have to sort it out for yourself.

Another rider’s line, even if he goes faster than you, might not be the correct one for you. Information can be valuable but you have to watch where it’s coming from and who’s giving it.

Other riders are often operating from their own false information. Pick it up and you will try to make it work, too. It can waste your time and energy.

Keith Code’s advice in A Twist of the Wrist echoes advice from a lot of self-help people who say that you have to “be your own hero”, as David Goggins said in his book, for example.

Everyone has advice for everything in your life: relationships, health, careers, and pretty much everything else. It’s all worth listening to, but you need to apply a filter to help you think: Is it correct? Is it relevant to me?

Be willing to fall down… or don’t ride

Finally, Code says the best riders are those who mentally accept they may fall. You don’t have to want it, but you have to accept the whole package.

As a racer, you should be willing to fall off. You don’t have to want to, but being willing to is very different and it has to do with your attitude about falling.

If you ride a motorcycle and especially if you race one, falling is an activity you’re likely to become involved with. It goes with the territory of riding. If you resist falling, you are more likely to fall. This is the key.

The more you resist it or fixate on the idea of not falling, the more it will take your attention away from your riding. You can spend your entire attention resisting falling. Then, because you have no attention left to operate the machine, fall from a mistake.

Here, again, is the magic of the decision. You simply decide that you might fall off and accept that it can happen, at any time, anywhere.

You have to look at it and say, “Okay, I can fall off one of these things. I might break a bone or have a hell of a slide or I just might die doing it.”

All of these things can and do happen to motorcycle riders.

So, get it out of the way by taking a look at it and then making your decision from there. I wouldn’t advise racing to anyone who wasn’t willing to fall down.

I think this is the ultimate lesson for anyone starting any difficult endeavour. Don’t even just be willing to fall: assume it will happen, and maybe for circumstances outside your control. Take ownership of it. If you don’t want to fail… don’t start.

If you don’t quite want to think of “falling down”, think of other failures you might be willing to accept: being passed, coming in last, or being lapped! Accepting the possibility failure is key to experimentation and progress.

Also — in motorcycling — wear a helmet (and your gear). (Goes without saying at the track, where it’s mandatory to have full leathers.)

Great summary. How about lessons from vol. 2?

Volume 2 book was a more technical book. It didn’t really have “life lessons” like the first one did. But I’ll put a summary up at some point.