Two motorcycles I’ve always had my eyes on from the BMW stable are the K 1200 S and K 1300 S, as well as their closely-related siblings, the K 1200 R and K 1300 R (and the GT).

These bikes are epic. A roaring engine that kind of feels like a car’s engine in the way it revs… except it would drive the most berserk car imaginable, a tiny rocket of an impractical go-kart. They’re comfortable, classy, and easy on the eye, with those angular sport bike looks that remind me of 80s Italian sports cars.

Somehow, they’re largely overlooked as used bikes. I think it’s because you compare these to the likes of the Suzuki Hayabusa or the Kawasaki ZRX1400R, which, in many ways, are better bikes — more focused on the “high speed in comfort” niche.

But the BMW, as usual, does its thing with class. These two bikes are reliable, easy to ride, and capable of doing a lot.

Here’s a quick overview.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

Before the BMW K 1200 S — How Did We Get Here?

I think it’s interesting to look at the historical context of the 2005+ K 1200 and K 1300 bikes.

Before the S 1000 bikes, which have taken over the zeitgeist, most people, when they thought of BMW motorcycles, would think of the boxer motors. These were what BMW started with a century ago, and they still feature in BMW’s highest-end motorcycles, like the R 1300 range. (See here for the history of BMW engine types.)

But BMW has been building inline multi-cylinder engines since the eighties.

Right before the K 1200 was… the K 1200. But the other K 1200 was a different kettle of fish, so much so that BMW did consider renaming the K line (per this article from the Cycle World archives), but didn’t.

Since the early 1980s, BMW had been building inline 3- and 4-cylinder engines in a horizontally mounted fashion, in the so-called “flying brick” configuration. The engine was flat, with the heads on one side and the crank (really, it should be the tail…) on the other.

The flying brick configuration was interesting in many ways. It kept the centre of gravity low. And it led to an interesting kick to one side when you started or revved the motor, similar to boxer motors, because the heavy engine crankshaft runs longitudinally and thus creates a torque reaction as it increases in rotational speed.

The last motorcycle engine in this “flying brick” series was the K 1200, and I had one of these, in RS format.

There wasn’t a naked version of this bike. Instead, there was only a version with ALL THE FAIRING IN THE WORLD!! Also, a GT version, fine. It had a powerful motor (130 hp peak), a liquid-cooled inline four-cylinder engine. It was by no means weak, but nor was it very fast. How could it be — the thing weighed around 300 kg, or many, many more pounds. Still, I liked it, if only because it put me in the exclusive “weird BMW” club, which resulted in old bearded guys wearing Aerostitch Roadcrafter suits giving me knowing nods of approval. Pretty good, I guess…?

The K 1200 RS (and GT) had a few elements that would be present in the later K 1200 and 1300 models: a liquid-cooled, inline four-cylinder engine, BMW lever-type suspension, a shaft drive, and comfort for days.

But then BMW went and changed things by deciding to orient the engine in a crazy new way — transversely (rather than horizontally in the “flying brick” configuration), and angled forward.

The 2005 K bike was completely different from its predecessors. It was the first BMW sport bike designed to be competitive with Japanese offerings — never mind that the S bikes, to be released just a few years later (starting with the BMW S 1000 RR, see its model history here), would be the real competitors. This was more of a “Bavarian Hayabusa”, as it was informally known.

Still, the new K bike was a compromise. It’s a high-performance machine, no doubt, but still heavy, optimised for comfort, and designed for the long haul. It was intended to be a sport bike, not a superbike, with no plans to race it.

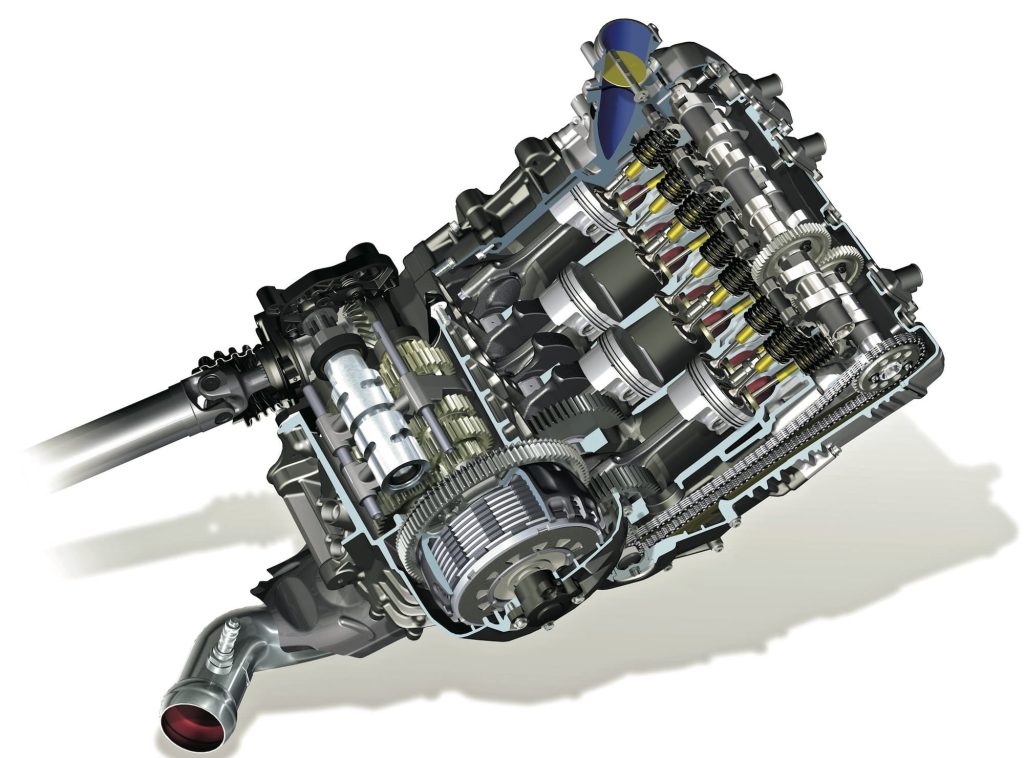

The first, most important change, was to use a transverse inline four-cylinder engine. This is the same orientation of inline four-cylinder engines as everyone else — don’t be spooked by the word “transverse”. BMW wanted to keep this engine high power, low weight, and minimally impacting the handling of the bike.

The first two points are unsurprising, but the last one, that of wanting to minimally impact handling, was pretty key. BMW oriented the engine way forward, angling it 55 degrees — not flat, but overmhalfway there! Because the new K bike is so long, the effect of pushing the crankshaft back was less significant. This, coupled with the dry sump design (the oil tank and filler cap are under the seat!), keeps the centre of gravity very low, a couple of inches below most sportbikes, if you take BMW’s word for it.

The rest of the engine design is less shocking – it has a dual overhead cam design, with sixteen valves. The exhaust cam is chain-driven, but the intake cam is gear-driven.

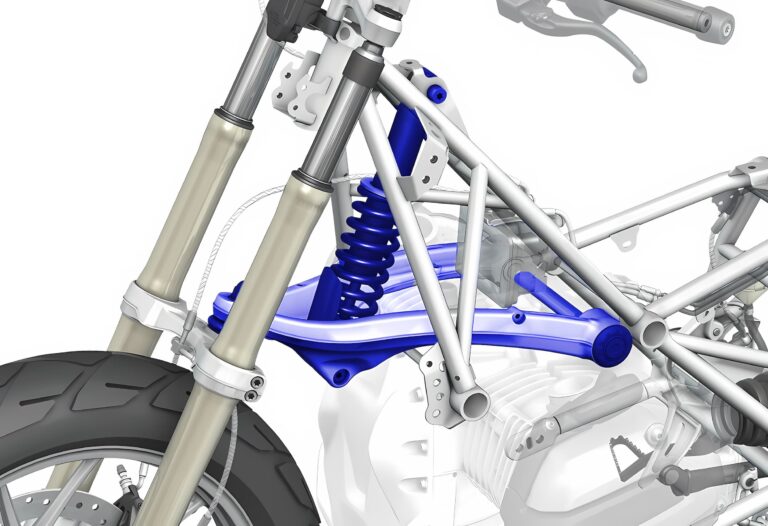

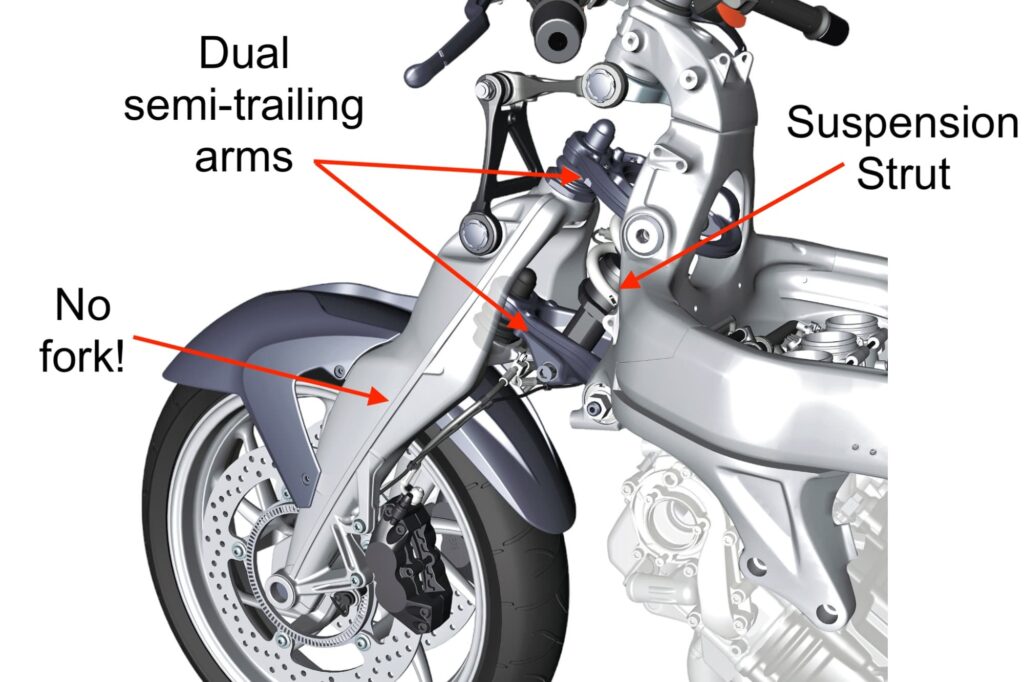

The second important change was “Duolever” suspension. This design means the fork parts are just there for steering the wheel (which means they can be much lighter weight), and there’s a little A-frame with a single suspension unit to take care of suspension. Again, this is longer, but so what, this is a long bike!

The Duolever setup gives the same advantages as the Telelever design used in GS bikes — separating suspension from steering means you can eliminate dive. Still, BMW tuned in a bit of dive, to give some of the semblance of the feel of a telescopic fork. See more about this in the guide to BMW suspension systems.

BMW also reinvigorated the rear suspension. It’s still “Paralever”, with one obvious change being that BMW repositioned the torque arm to be above the axle, rather than below it, allowing for more clearance. BMW also gave the K 1200 S a rising-rate linkage system (also known as a progressive system), which changes the leverage ratio as the rear wheel moves through its travel, allowing for soft suspension at first but significantly stiffer suspension as it compresses. Awesome! On top of that, you could adjust the damping of the rear shock electronically if you got ESA (and many did opt for ESA).

The new K bike also got a CAN BUS electrical system, which had debuted a year earlier on the R 1200 GS. This means that instead of a hefty wiring loom, there are just twisted pairs of wire to send digital signals between computers on different parts of the bike. It was good news at first but some found it tricky to diagnose problems, as you can’t with a simple multimeter.

A further innovation in the K 1200 S and R was the multi-plate wet clutch — despite keeping the shaft drive. BMW had primarily used single-plate dry clutches in its motorcycles with longitudinal crankshafts, mounted between the engine and gearbox. These were on boxer twins (in fact, the BMW R nineT and current R1 2 nineT still have a dry clutch!) and K bikes up to the K 1200 RS / GT. But the K 1200 S got a clutch that’s bathed in engine oil, is mounted on teh crankshaft axis, ahead of the gearbox, and is integrated into the compact casette gearbox. The wet clutch meant clutch engagement could be smoother, smaller, and lighter.

Finally, BMW shifted the frame from a heavy steel/aluminium hybrid to an aluminium twin-spar frame that used the engine as a stressed member, allowing for a huge weight loss.

OK, on to the bikes themselves.

BMW K 1200 S (2005-2008)

First up was the BMW K 1200 S, released for the 2005 model year. I’ve already talked about what made it different above, but let’s look at that in table format.

| Feature | K 1200 RS (“Flying Brick”) | 2005 K 1200 S |

| Engine Layout | Longitudinal (Inline-4 laid flat) | Transverse (55° forward tilt) |

| Capacity | 1,1711 cc | 1,157 cc (bit smaller, but who’s counting?) |

| Bore x Stroke | 70.5 x 75.0 mm (Long-stroke) | 79.0 x 59.0 mm (Short-stroke) |

| Compression Ratio | 11.5:1 | 13.0:1 |

| Power | 96 kW / 130 PS @ 8,750 rpm | 123 kW / 167 PS @ 10,250 rpm |

| Peak Torque | 117 Nm (86 lb-ft) @ 6,750 rpm | 130 Nm (96 lb-ft) @ 8,250 rpm |

| Wet Weight | 285 kg (628 lbs) | 248 kg (547 lbs) |

| Front Suspension | Telelever | Duolever |

| Wiring System | Traditional wire bunch / Fuses | CAN BUS (Digital) |

| Clutch | Dry, single plate | Wet, multi-plate |

| Transmission | Separate External Unit | Integrated Cassette-type |

But even without considering the specs, it’s obvious that the K 1200 S is just a sharper machine. It looks great! While the K 1200 RS was a little bulbous and retro, the K 1200 S has looks that I believe have stood the test of time — if a little retro, sure.

Notice that the single-sided swing arm leaves the wheel exposed on the right. This is a design choice that BMW made (across the range of shaft-drive motorcycles) purely for aesthetic reasons (compare it to the K 1200 RS image above), so riders could admire the bike as they walk away. Seriously, that’s the reason.

Stepping astride a BMW K 1200 S, you immediately feel the difference. It’s narrower, noticeably lighter, and feels sportier, like a Hayabusa.

But unlike a Hayabusa, you’re not canted over quite so far. The Hayabusa has “comfortable sport bike” ergonomics. The K 1200 S has “sport touring” ergonomics.

Revving both motors is quite a different experience, too. The K 1200 S, with its shorter stroke design, is much freer revving. It’s intended to rev high. In testing, they took it up to 20,000 rpm and it didn’t blow up. In practice, the redline starts at 11,000 rpm, and good luck getting there in many gears at legal speeds.

There are a few problems the K 1200 developed over the course of time that need to be mentioned.

Firstly, there was an issue with the cam chain where it would sometimes “jump”, with leading to either noisy operation or serious engine damage. The problem would arise with failure of the hydraulic tensioner. Careful owners would install an updated tensioner and a plastic cam chain jump guard, as recommended by BMW service bulletins. Later models came with this fix installed. If you’re buying a used one, confirm that the guard was installed.

Secondly, the servo-assisted brakes on the K 1200 S (and a few other BMW bikes of the era, like the early BMW R 1200 GS) is a notorious weak point. Even with regular maintenance, they can fail, which leads to a hard brake pedal (i.e. you press hard and it does nothing), a warning light, and sometimes even locking up. Because they’re so expensive to replace, some people bypass them entirely.

Thirdly, the early generation of the oil-bathed clutch basket could wear quickly. This leads to clunky operation or struggling to find neutral.

Finally, and maybe most annoyingly, BMW had this issue with the fuel sensor in the K 1200 S and R. They used a flexible plastic strip with conductive tracks to measure the fuel level. The problem was, these strips were highly fragile and often broke internally, leading to false readings, warning lights, incorrect range data.

Some of these are endemic to just the K 1200 S and R, and some of them are just “old bike problems”. But anyway, the general consensus is that the 1300 was the better generation of bike, as it mostly resolved those issues.

BMW K 1200 R (2005-2008)

BMW launched the K 1200 S and K 1200 R at the same time, but the K 1300 R became available some time afterwards — in some markets, only as a 2026 model.

It is, as you’d expect, a stripped-back K 1200 S. It has the same engine, but slightly different air inlet, leading to (trivially) lower power and torque specs. But BMW did change the final drive ratio, increasing it from 2.82:1 to 2.91:1, more suited for low-end thrust rather than top-end speed. To complement this and the lower weight, BMW also made some adjustments to the suspension.

| Item | K 1200 S | K 1200 R |

|---|---|---|

| Peak power | 123 kW / 167 hp @ 10,250 rpm | 120 kW / 163 hp @ 10,250 rpm |

| Peak torque | 130 Nm / 96 lb-ft @ 8,250 rpm | 127 Nm / 94 lb-ft @ 8250 rpm |

| Final drive ratio | 2.82:1 | 2.91:1 |

| Rear tyre | 190/50 ZR 17 | 180/55 ZR 17 (Optional 190/50 ZR 17) |

| Wet weight | 248 kg / 547 lb | 237 kg / 522 lb |

The most important difference is the comfort and riding position. The BMW K 1200 R’s handlebar is wider and taller than the bars on the K 1200 S, which means you sit on the bike with a more upright position.

And of course, the K 1200 R has that badass, asymmetrical headlight configuration that’s hard to take your eye off. It’s a pretty cool-looking bike.

But wait… is the K 1200 R (and its successor, the 1300 R) ugly?? I was shocked when reading about it to find that some find its brutish looks unappealing. I get it; it’s not svelte like a sport bike. Some people just don’t like naked bikes at all. But anyway, I hadn’t even questioned that this is a good-looking motorcycle — just shows how subjective tastes can be.

BMW K 1300 S (2009-2016)

BMW replaced the K 1200 models with the K 1300 models for the 2009 model year. Yep, the same model year as the first S 1000 RR!

So, what would draw people to the K 1300 S? Fundamentally, it’s the same bike, but with more of everything.

Firstly, the engine. BMW increased the displacement, and also the total power output – the new 1,293 cc motor made a peak of 129 kW / 175 hp. The original wasn’t shy on power, but more is always more.

Here’s a table of the spec changes in a nutshell.

| Item | K 1200 S | K 1300 S | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engine capacity (cc) | 1,157 cc | 1,293 cc | More capacity |

| Bore × stroke (mm) | 79.0 × 59.0 | 80.0 × 64.3 | More bore, more stroke. More everything! |

| Peak power (kW / hp) @ rpm | 123 kW / 167 hp @ 10,250 rpm | 129 kW / 175 hp @ 9,250 rpm | Power delivered lower. (Same redline) |

| Peak torque (Nm / lb-ft) @ rpm | 130 Nm / 96 lb-ft @ 8,250 rpm | 140 Nm / 103 lb-ft @ 8,250 rpm | Much stronger low–mid range (+10 Nm from ~2,000–8,000 rpm) |

| Front suspension | Duolever (steel lower arm) | Duolever with forged aluminium lower arm | ≈1 kg less unsprung mass |

| Rear suspension | Paralever, ESA I optional | Paralever, revised geometry, ESA II optional | ESA II adds spring-rate adjustment |

| Rear tyre | 190/50 ZR17 | 190/55 ZR17 | Slightly taller profile |

| Wet weight (fully fuelled) | ~248 kg | 254 kg | |

| Frame | Aluminium bridge frame | Aluminium bridge frame (unchanged) | |

| Brakes / ABS | EVO brakes, Integral ABS (semi-integral) | EVO brakes, Integral ABS (revised tuning) | |

| Ride aids | Not available | ABS, optional ASC (Anti-Spin Control), HP Gearshift Assistant | |

| Engine management | BMS-K | BMS-K with cylinder-specific knock control |

So, BMW pulled a rabbit out of its hat and delivered a bigger motor with the same redline, but with more torque through the whole rev range, and peak power delivered lower. Great! All this at a 6 kg weight penalty, which isn’t that much, on this size of bike.

Aside from the engine update, BMW upgrade a bunch of things in the K 1300 S.

The second generation of ESA, ESA II (optional at the beginning, on the base model), gives more adjustability from the cockpit — you can modify not just the springs and dampers, but also the spring pre-load (which BMW calls the “spring base” or “pre-tension”) and spring rate.

BMW made special electronics (ASC and the Gearshift Assistant) and the Akrapovič silencer optional at the beginning, but introduced them as standard in several packages, like the “30 Jahre K-Modelle”, a.k.a. the 2013 model that comes in a delicious “strawberries and cream” colour scheme.

The gearshift assistant is an up-only quickshifter and is quite well liked.

Like many BMW motorcycles (heck, even Harleys!) from the factory floor, the K 1300 S and R can sound pretty pedestrian idling. Sure, they’re more exciting at higher revs, but they really do need an exhaust pipe to open them up. The factory option of the Akrapovič exhaust is probably the best way to go, since in regions where it’s hard to keep your vehicle street legal, it’s best to go with options that come from the factory. Besides, it does sound good, with a burble at idle and a bassy scream at high revs. Very Hayabusa-like!

One small but noteworthy thing is that the K 1300 S finally got the modern, standard way of activating turn signals. No more of the paddles (which have their loyal fans, I know!), but just the little knob on the left. For those of us who switch between bikes, this is very welcome!

One of the best pitches for the K 1300 S and R is that BMW resolved the high-stakes mechanical ane electronic gremlins:

- The K 1300 came standard with the upgraded cam chain tensioner and a jump guard to prevent catastrophic engine failure.

- BMW dumped the servo-assisted ABS, replacing it with a much more reliable and standard feel Teves ABS system.

- BMW worked over the clutch (and transmission) on the K 1300 generation, eliminating clunkiness and premature failure.

BMW made other updates to fuelling and electronics for general easier riding and reliability.

BMW K 1300 R (2009-2016)

Again, BMW released the K 1300 R contemporaneously with the K 1300 S, bringing the post-apocalyptic doomsmobile looks with it.

The differences between the K 1300 S and R are very similar to those on the K 1200 bikes. The power difference is purely from the way the engines breathe — there’s no difference in the engine design.

| Item | K 1300 S | K 1300 R |

|---|---|---|

| Peak power | 129 KW (175 hp) at 9,250 rpm | 127 kW (173 hp) at 9,250 rpm |

| Rear tyre | 190/55 ZR 17 | 180/55 ZR 17 (190/55 ZR 17 optional with sports wheel) |

| Final drive ratio | 2.82:1 | 2.91:1 |

| Wet weight | 254 kg / 560 lb | 243 kg / 536 lb |

Even though the R is the naked bike, many find it easier to ride fast in dynamic (twisty) situations, as the handlebars give you more leverage. I’ve known one guy, at least, who chose the R, and he spends quite a large portion of the day at speeds that would have me constantly looking over my shoulder… he lives in the middle of nowhere, though.

BMW K 1300 GT (2009-2010)

The last K 1300 bike worth mentioning is the K 1300 GT. This is a more sedate bike, designed for long-range touring and … cops! (It was a police bike in some European markets.)

The BMW K 1300 GT is a full-fat tourer that shares the same engine dimensions as the K 1300 S, but with different tuning. It has a more comfortable riding position, a tall, electrically adjustable screen, that huge fairing, and every feature available at the time.

BMW tuned the 1300 motor to produce 118 kW (160 hp) at 9,000 rpm, with hefty torque of 135 Nm / 99 lb-ft at 8,000 rpm. Sure, it’s not as much as the K 1300 S, but it’s still a lot of power! BMW also tuned the engine to produce 80% of its torque from as low as 3,500 rpm, with a big fat torque curve for everyday riding and touring.

Everything on the K 1300 GT is designed for comfort. The screen is adjustable, the seat is plush, and you can even adjust the handlebar for height in four levels.

On the seat: I’ve read some accounts where people think the seat is NOT comfortable. Maybe I just am a sucker for hardship? I ride a pushbike for hours at a time… we all have different standards. Anyway, there are even more comfortable aftermarket options.

What I like about the K 1300 GT is that it’s like flying in a luxury jet. It has that Yamaha FJR 1300 feel… actually, come to think of it, they have quite a lot in common! The four-cylinder engine just purrs (a bit like a small-displacement BMW car), it’s comfortable, and you’re always protected from the elements. In fact, unless you’re unusually tall, you can adjust the windshield to the point where you’re sitting in a bubble of protected air. See? Like a jet!

But even the GT had many options, including ESA II, heated grips, a heated seat, cruise control, ASC, and a high windshield. The good news is that the well-to-do buyers of GTs generally fitted everything. Have a look in the classifieds (I just did) if you don’t believe me!

With the comfort options and the engine that seems happy at any speed, the BMW K 1300 GT is capable of just about anything. With that said, it suffers a bit from what I think of as the one drawback of bikes that make everything too easy… they do take a bit of the challenge away. It’s utilitarian.

Maybe the only fly in the ointment of the K 1300 GT is something the K 1600 introduced — a reverse gear. You only realise you need it when you’re parking (or trying to get out of a parking spot) and swear under your breath and think “You know what would be useful here…”

The BMW K 1300 GT was only in production for a couple of years. BMW took a break from this class of bike, but eventually, the K 1600 took its crown.

What Came After the K 1300 Bikes

Technically, there’s still a K bike being made – the K 1600. But it’s a very different beast. Nobody really compares it to the K 1300. I guess BMW has a tendency to have a very generous definition for what makes a “K” bike.

If the K 1300 GT was like a luxury jet, then the K 1600 GT is like a luxury Boeing 747. It’s big, it’s cruisy, it’s powerful, and it’ll take you pretty much anywhere.

The elephant in the room is that engine. Still canted forward, the K 1600 GT has a 1649 cc inline 6-cylinder engine. It makes the same peak power as the K 1300 GT, but more torque (175 Nm or 129 lb-ft), and from way down low, peaking at 5,250 rpm.

The engine in the K 1600 GT is incredible. I don’t know if I’ve had a smoother engine outside … maybe a BMW M2? Is that a fair comparison? Look, I don’t know BMW cars so well, and that’s one of the few I do know, so it’ll have to do.

The K 1600 GT, being a later model bike, came with loads of innovations. Let’s not go into those — because I’m sure if BMW kept the 1300 in production, it would also have received those innovations. What I think is most distinctive is that there is no longer an S nor an R version of the K 1600.

There’s no K 1600 S, nor a K 1600 R. It’s a bit of a shame. Fans of the Honda CBX1000F, an iconic bike with an in-line six-cylinder engine, might be interested in a K 1600 R. But they might also be disappointed, when they realise the engine doesn’t respond the same way, peaking in torque at 5,250 rpm and having a redline just over 8,000. With the large displacement, it’s just not the same thing.

Anyway, writing about the K 1600 GT and GTL is for another day. It’s a great bike; just a bike of a different flavour, for a different market.

Wrap Up

The BMW K bikes are great value. Sometimes people overprice them, charging what I think is too much for a 50,000 km (or 30,000 mile) bike from a decade ago — dealers tend to ask for more realistic prices than individuals, who always think what they have is special.

Sport tourers aren’t the darling of motorcycles they once were. People are more obsessed with adventure bikes (like the R 1300 GS), sport adventure touring bikes (like the S 1000 XR), or more focused sport bikes. Basically, “do-it-all” motorcycles are popular either with older people who finally want to do the lap of the world, or police forces.

But this doesn’t mean they don’t deserve to exist. The days of being able to legally buy something that can do over 200 km/h and that you’re allowed to pilot yourself will come to an end. Everyone should try a high speed tourer while they can… and the K bikes are a great choice.

![Buying a Honda CBR600F, CBR650F and CBR650R [Updated for 2024] 17 Honda CBR600F Buyers Guide - CBR600F4i Red and Black](https://motofomo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CBR600f4i-red-1-768x441.jpg)