Learning about BMW motorcycle engines I kept hearing terms like “hexhead”, “oilhead”, “airhead” and so on.

I’m not 100 years old. Nor am I a historian. So a lot of the history here is from BMW’s very long and detailed “90 years of Motorrad” released by the BMW press team in 2013. It doesn’t include the last couple of generations of motor, so I added that from other BMW sources.

A lot of the other information I gleaned from looking up spec sheets for specific models. Thankfully, the names are pretty consistent. People tend to give general information on forums, but unless they’re an old-hand BMW mechanic (or historian), they sometimes generalise to a model with which they’re familiar (like the GS), or give vague dates.

These names — Oilhead, Airhead, Wethead and so on — aren’t official names for BMW motorcycle engines (can you imagine BMW corporate calling something a “Flying Brick,” or “Fliegender Ziegelstein?” I think not) But still, I’ll capitalise them, as they’re like affectionate nicknames, just like people a few call me The Hoosh.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

BMW Motorcycle Engines Overview

Any history of BMW motorcycles can be told in a few ways. But heavily intertwined with the history of the bikes as a chassis is the history of BMW motorcycle engines.

This is particularly true when you look at Airhead engines. The below is an abbreviated history, and any Airhead nerd will be able to tell you the differences between the generations of Airhead engines. I can’t, yet. Also, these motorcycles are so old and classic that they’ll take an outsized proportion of my carefully hoarded motorcycle budget, which could otherwise be spent on a lot of other bikes.

But what’s really interesting is that the first generation of BMW motorcycle engines, the Airheads, lasted the vast majority of BMW’s life. Many of the other iterations (like Oilheads, Wetheads and so on) came in the last thirty years. BMW developed their motorcycle engines seemingly as quickly as the rest of the world developed everything else.

And while two-cylinder horizontally opposed twins (I mean “Boxer twins”!) are great, it’s not even the whole story of BMW motorcycle engines. Because aside from boxer twins, BMW has produced engines in configurations including:

- Inline 3 and 4-cylinder engines horizontally/longitudinally mounted (from the K 100 to the K 1200 in some variants)

- Inline 4-cylinder transversely mounted engines (from the K 1200 in some other variants to the K 1300)

- High-performance 4-cylinder transversely mounted engines (S and M series)

- Single-cylinder engines (a.k.a. “thumpers”), including the F 650 GS, G 650 GS, G 310 R and many others probably

- Parallel twins with a 360-degree crank, including the F 800 GS, F 800 R and many others (usually with ~ 800 cc)

- Parallel twins with a 270-degree crank, including the F 900 R and F 900 XR

- Inline six-cylinder engines in the K 1600 motorcycles

I’m sure there are people among you who can point out many other examples of the above engine configurations, especially some of the smaller ones like single-cylinder engines or small twins.

But most would also agree that the classic BMW motorcycle engines are boxer twins. To a lesser, but still very important extent, the K-series horizontally mounted engines are also classics. The other engines are great (I really love my S 1000 R for its fiery character but sedate suburban manners), but they’re not as iconically BMW — yet.

BMW Airhead engines — The Originals (1923-1992)

The history of BMW motorcycles and BMW motorcycle engines starts with the Airheads.

Airhead engines are the old-style 2-valve air-cooled boxer engine made before 1992 when the last of them were made. They weren’t called “Airheads” at the time by anyone because they were all BMW-made!

The first motorcycle BMW made was the BMW R 32. BMW launched it at the Berlin Motor Show in 1923. The BMW R 32 had an air-cooled twin-cylinder four-stroke boxer engine and manual gearbox driven directly by a friction clutch and shaft drive. If that sounds familiar, it’s because I could have just described the 2021 R NineT (although that’s also oil-cooled, i.e. it has an oil cooler out the front).

Like the R 32’s engine, many BMW Airhead engines that followed it for decades were air-cooled. They had one camshaft that drove overhead valves via pushrods and rocker arms. Each head had one spark plug and two valves, and they were all carburettor-fed.

When you see “classic” BMW motorcycles (often sold at a premium, or rebuilt into cafe racers and shown on BikeEXIF), the vast majority are Airheads. Airheads have a special following. The owners are protective about the name, and I’ve been corrected a couple of times in the past when I thought an oil-cooled engine was an Airhead… it wasn’t!

There were many Airhead BMW motorcycle engines produced over the years, maxing out at near 1000cc. One of the last Airheads was the R 100 GS, produced up to 1992. It had a 980cc air-cooled boxer twin engine.

BMW Oilhead engines — More Oil Cooling (1993-2005)

Many used and “not-quite-classic-but-not-that-new” BMW motorcycles have Oilhead engines.

The name “Oilhead” comes from the fact that the engines were redesigned to flow oil around the engine head to cool it. Oilhead BMW motorcycle engines gain an oil cooler (which looks like a little radiator), which BMW hides away under the fairing if there is one.

BMW Oilhead engines are 4-valve-per-cylinder air- and oil-cooled boxer engines made from 1993 to 2005.

The first BMW motorcycle with an Oilhead engine was the BMW R 1100 RS sports tourer which had a 1085cc engine (“1100” was just the naming convention).

The R 1100 GS got the Oilhead engine shortly afterwards.

These bikes with Oilhead engines weren’t just an engine update. They brought a lot more technology to the Boxer series, introducing fuel injection and ABS in some models. (Previously, the “Flying Brick” BMW K 100, first introduced in 1983, became the first motorcycle to have ABS in 1988.)

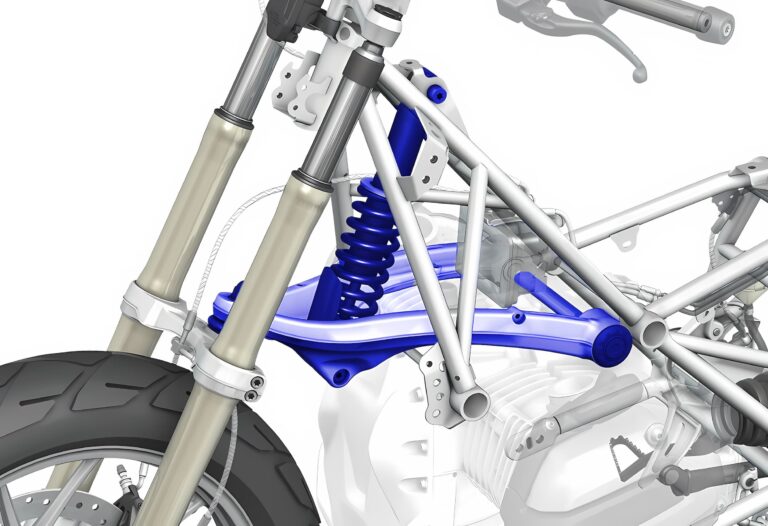

The Oilhead R 1100 motorcycles were also the first with Paralever front suspension. See the wishbone strut sticking out from behind the fork tubes. But that’s another story!

Oilheads aren’t that different from other air-cooled engines that use oil and a cooler (like my early Ducati Monster, for example). BMW circulates oil around the exhaust valves and through an oil cooler.

It’s just a way of cooling the engine that doesn’t involve water, keeping one less element to worry about, and keeping away the need for a radiator.

BMW introduced oil cooling because the need for cooling increased with the higher engine capacity and power output. But the compact cylinder head between the larger valves, coupled with the narrow valve gap, meant that air flow was insufficient.

Oilhead engines are air- and oil-cooled with two cams per motor, each cam above the crankcase but not in the cylinder heads. They have short pushrods and conventional rocker arms.

Early Oilheads had one spark plug per cylinder but later had two. All have four valves per cylinder.

Early Oilheads were 1085cc (called R 1100 in motorcycle names), with an 850 produced for a few years, like in the R 850 R, though BMW stopped making small boxers. A few later models were called R 1150 and had 1130cc engines.

The Oilhead was replaced by the Hexhead starting in 2004 (GS and RT), but the Oilhead continued for another year in the R 1150 R, the last of the Oilheads (and also in the Chromehead).

BMW Chromehead engines (a sub-type) (1998-2005)

A sub-category of the Oilhead is the Chromehead BMW motorcycle engine, which is an Oilhead that is chromed on the outside for aesthetic purposes but is otherwise exactly the same as the Oilhead. The BMW R 1200 C (the cruiser) and CL (the big comfy tourer) had the Chromehead engine.

The R 1200 C sold well in the US, mostly on the back of its style. I mean, it was fine to ride, but its performance wouldn’t set the world on fire — but those looks were (and are) very unique.

A lot of R 1200 C’s fame at the time came from the fact that it played a big part in a James Bond movie — Tomorrow Never Dies, played by Pierce Brosnan. Apparently, in production, they used *fifteen* Rc1200cC bikes, 12 of which were destroyed.

In the scene, Bond stole the bike (I have no idea how he did so so quickly, or where he found a brand new BMW in Saigon, a city in which slightly old scooters and farm bikes were 99% of the motorcycle population), used it to race around the streets and rooftops, and even jumped from one rooftop to another over a helicopter that seemed to be intentionally ducking for the moment. Still, awesome.

(I’d have picked a dirt bike… and also, I’d definitely have very early in the chase been hit by one of the million bullets, or failing that, crashed my bike.)

BMW Hexhead engines (2005-2009)

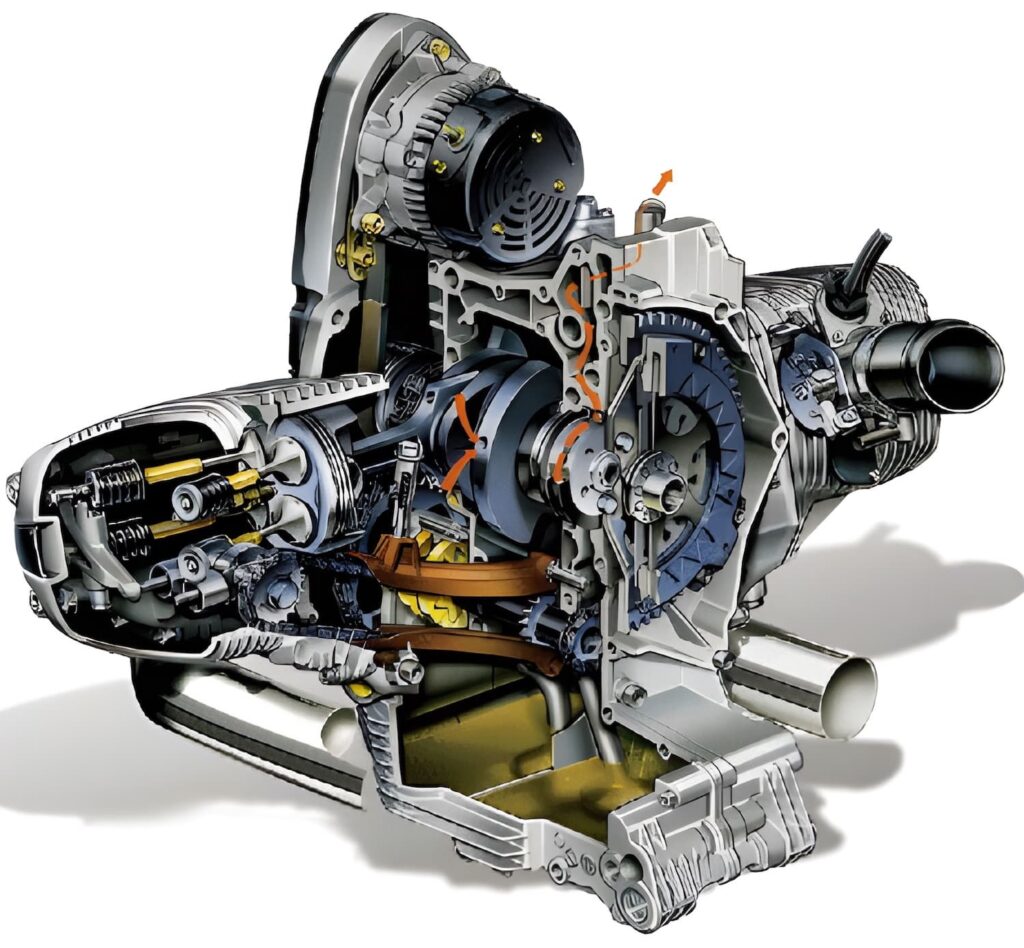

The Hexhead BMW motorcycle engine was an iteration of the Boxer engine in the R 1200 series of bikes since 2005 (with slight overlap with Oilheads and Chromeheads).

You can recognize BMW Hexhead engines by the somewhat hexagonal shape of the valve covers and heads (after which they were named).

The Hexhead engines were a major update to the 1150 series and had a bump in displacement to 1170 CC, getting the name “R 1200” in marketing. Aside from an engine update, the R 1200 GS was a very different motorcycle to the previous (also great) BMW R 1150 GS.

You probably know the R 1200 GS from a Starbucks near you, where I’ll have rolled up pretending it’s my first stop arriving after crossing the ‘Stans with nothing more than a tool roll, a hunting knife, and pure grit.

Hexhead engines are/were oil-cooled and had a single camshaft and four valves per cylinder, and two spark plugs per cylinder. The camshafts were above the crankcase but not in the cylinder head. They used short pushrods and conventional rocker arms to open and close the valves.

Aside from being more powerful and more advanced, Hexheads are also known to be easier to work on than their previous Oilhead counterparts. This is generally a trend that continued with the evolution of BMW engines.

Hexheads were the last BMW boxer engines — aside from the R 18 — to have screw-and-locknut type adjusters for the valve clearances. So even though valve clearances come up every 6000 miles / 10000 km (with oil changes), checking and adjusting the clearances is a relative doddle, the trickiest part being getting the engine in the right position.

Hexhead engines produced different power specs throughout the years. Early R 1200 GS motorcycles made ~100 hp at the crank, but my own BMW R 1200 S (that I miss a little) made a claimed 120 hp. Later R 1200 GS (but before an engine redesign) versions made a little more power through refinements to the engine and tuning.

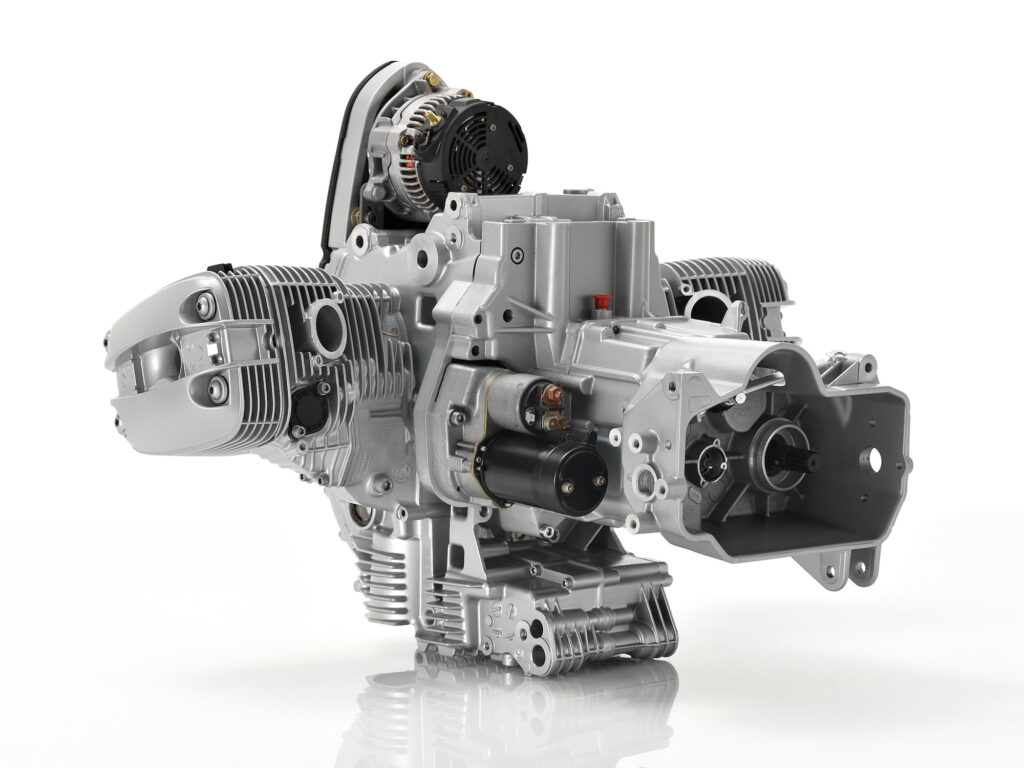

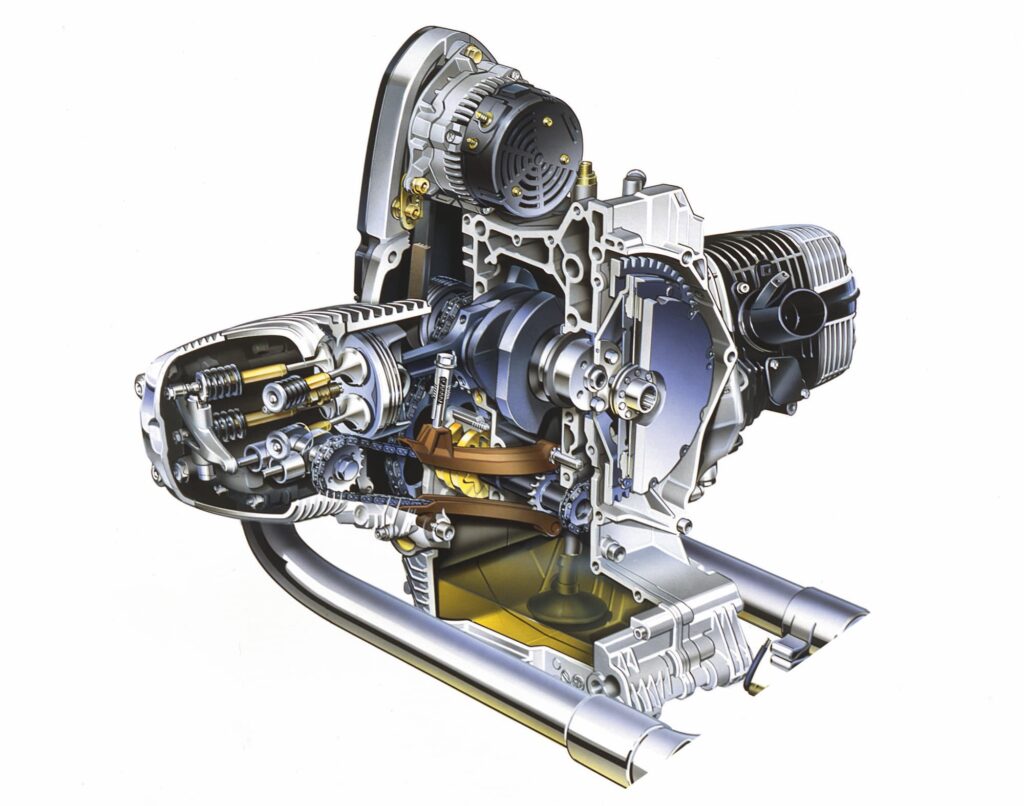

BMW Camhead engines (2010+)

In 2010, BMW started making their Hexhead engines with twin overhead cams. They’re still air/oil-cooled, but the twin camshafts give them their “Camhead” name.

These were the last air/oil-cooled engines BMW made before switching to partial water cooling with the Wethead engines.

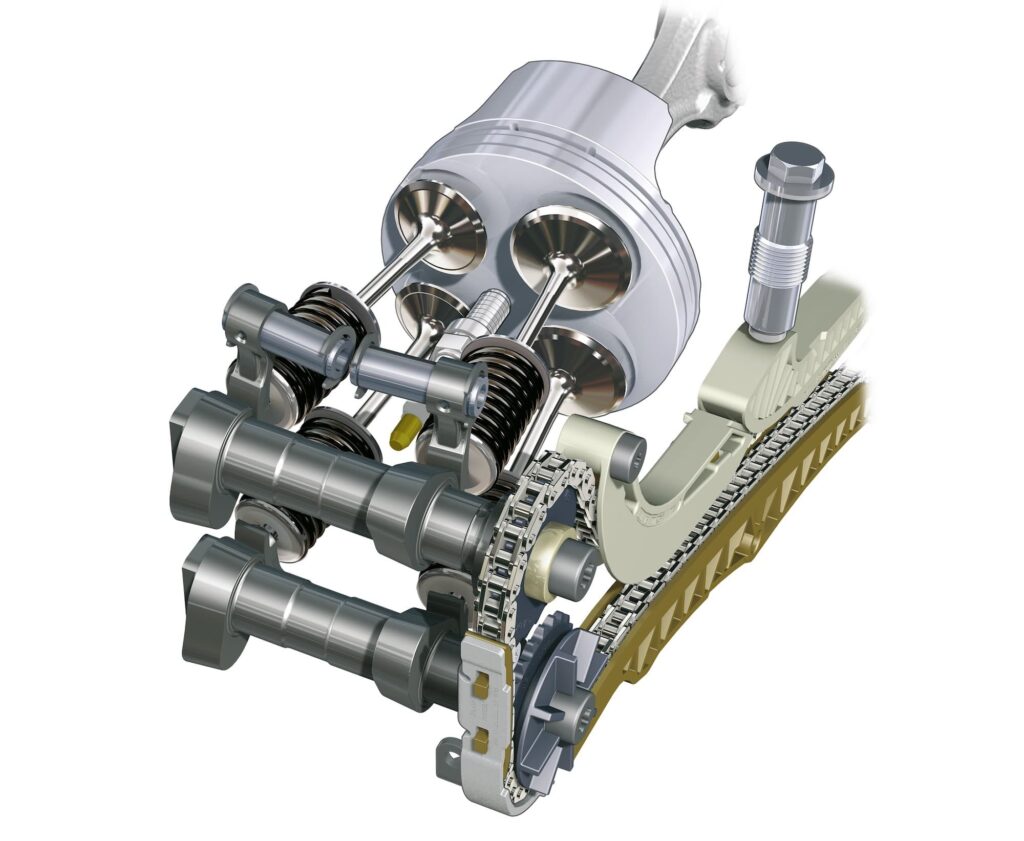

The Camheads’ twin camshafts are chain-driven and located at the top of the cylinder head, opening four valves per cylinder, as before (and firing through twin spark plugs, as before).

Bear in mind that Camheads are named for their internal design, not what they look like outside. They don’t look drastically different externally. But internally, the engineering is quite different.

The overhead cam design means that valve servicing is a trickier affair. Gone are the screw and locknut adjusters available up until the R 1150 — you now have a shim and bucket system, which means getting the camshafts out of the way to make changes.

Camhead engines were an important update, but the motorcycles didn’t get other major updates at the time. The R 1200 GS was still called the R 1200 GS for example, but if you ask aficionados, they’d recommend you get a 2010+.

Interestingly, BMW still uses the Camhead engines today in the R nineT motorcycles. Of course, some components have been upgraded, like the fuel injection computer and rider aids, plus frankly an innumerate number of other things, increasing over time.

But when released, the R nineT in 2014 used the same engine as the then R 1200 R (a Camhead). The following year, the R 1200 R became a Wethead.

See my guide to the BMW R nineT motorcycles here.

BMW Wethead engines (2013-2018)

BMW started making their liquid-cooled “Wethead” engines in 2013. They remain in production today, although they’re now “ShiftCam” variants. Wethead engines were 1170cc, just like the Camhead engines, and in motorcycles with the name “R 1200” naming convention.

Side note: Not everyone likes the name Wethead, which is a bit gross if you think about it too hard. Some alternative names have been “Showerhead” (which is also being used by Harley-Davidson for their water-cooled engines), and “Wasserboxer”, a name originally used to describe water-cooled boxer engines made by Volkswagen.

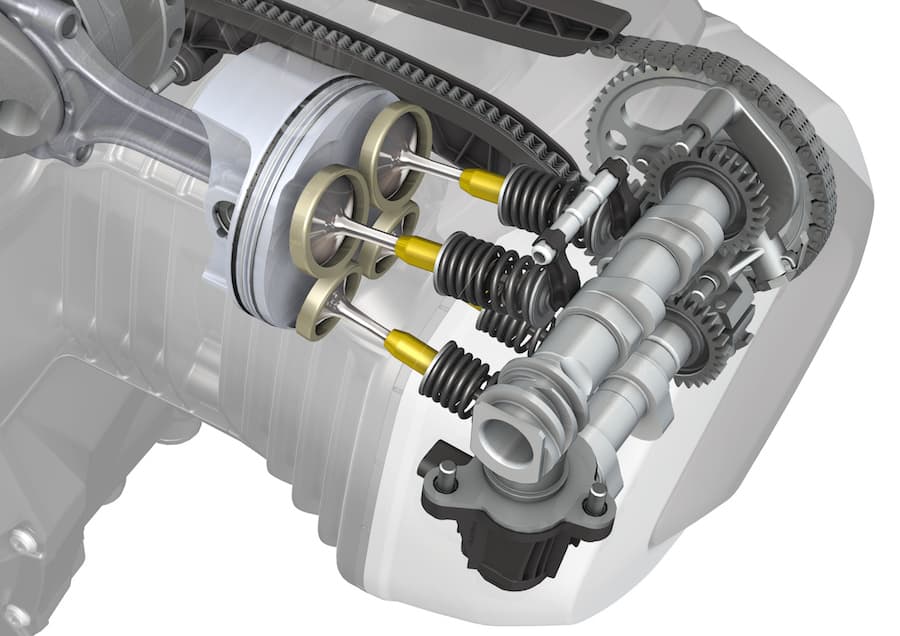

Wethead engines are oil- and liquid-cooled. They have two cams per head, the cams being chain-driven and in the top of the cylinder head (i.e. no pushrods). They work the same as Camheads, but the major addition is liquid cooling.

Liquid-cooling helps the Wethead engines by reducing mechanical noise, shortening the warm-up time, and improving combustion stability (translating to much reduced exhaust emissions).

If you’re interested in looking at a deeper dive in the benefits of liquid cooling vs air/oil-cooling in motorcycle engines, refer to this article here.

When BMW released the 2013 R 1200 GS, they made a point of saying that the new motor only had liquid cooling for the most critical components. They call it “precision cooling” and say they only cool components with coolant that are “particularly exposed to thermal stress” (i.e. that get very hot) and thus “the two radiators are small”. So liquid cooling doesn’t mean the addition of a huge radiator.

Many other brands also transitioned to water cooling from traditional air cooling (e.g. Triumph from 2016-onward, Ducati gradually in the 2010s) because they wanted to reduce noise and emissions, and also extract more power from their motors with higher compression ratios.

Wethead engines have four valves per cylinder, as before. But they only have one spark plug per cylinder. (Ed: Thanks for the correction, Mark!)

That said, even though it looks similar to the outgoing Camhead, the Wethead engine is completely new and doesn’t share most parts with earlier ones. Many R 1200 GS fans were a little sceptical at first (you can see if you dig into the old forums at ADVrider), but they’re now converts, realising the Wethead is both more reliable and easier to work on.

Wethead engines keep the “R 1200” naming convention, so, for example, the R 1200 GS was still called the R 1200 GS despite the new engine.

And not every motorcycle was updated right away. For example, the R 1200 R was updated to the Wethead design for the 2015 model year, two years after the R 1200 GS.

BMW 1250cc ShiftCam engines (2019+)

In 2019 BMW started making its 1254cc ShiftCam engines, which are the same as Wetheads but with larger displacement and new technology in the way the cams work. ShiftCam is variable valve timing, but implemented in a different way to how BMW ever used it in its cars.

(Note that the 2019+ BMW S 1000 RR engine also has ShiftCam variable valve timing, but people don’t talk about engine names for the S series.)

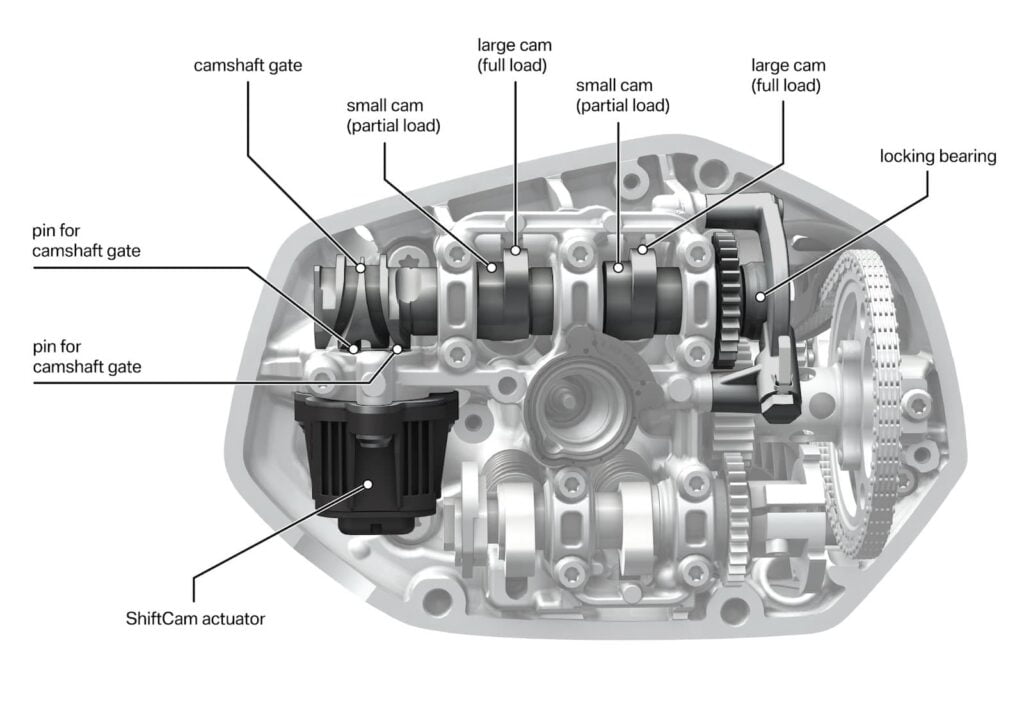

BMW’s new 1250 engine varies both valve timing and valve stroke on the intake side, optimising each to maximise low-end torque without compromising top-end power.

BMW also implemented intake camshafts that open the two intake valves asynchronously, thus swirling incoming mixture together and promoting more effective combustion. The inlet camshaft of each cylinder has two different cam profiles on the same shaft — a partial-load cam, and a full-load cam.

The way ShiftCam works is:

- When the throttle is partly open, or when the engine is low in the rev range, the cam has shorter lift and reduced duration, opening the inlet valve less and for shorter time.

- When the throttle is wide open or revs are high, the cam shifts sideways (get it? shifts!), changing the cam lobe for a higher-lift, longer duration one, that opens the inlet valve more and for longer.

The camshaft is shifted by a pin that’s actuated via the Bosch ECU. It locks into a gate in the camshaft. The camshaft rotates, which lets the pin draw the camshaft sideways. The change is almost instant — it takes just 10 milliseconds.

BMW released the BMW R 1300 GS for the 2024 model year in late 2023. It has a larger capacity engine (1300 cc, to be precise!), but uses the same ShiftCam architecture as the R 1250 generation. (See here for other changes in the R 1300 GS.)

BMW “Big Boxer” motor (2020+)

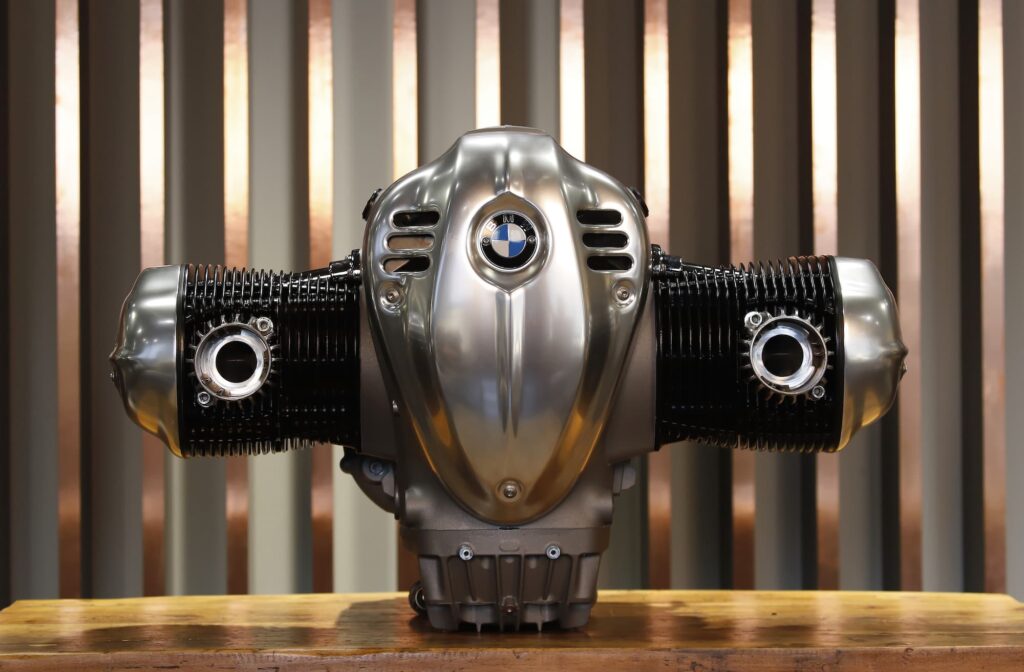

The latest in the BMW series of opposed twins is the “Big Boxer” that powers the BMW R 18.

This is an 1802 cc air/oil-cooled boxer twin. It’s the biggest boxer twin BMW ever produced!

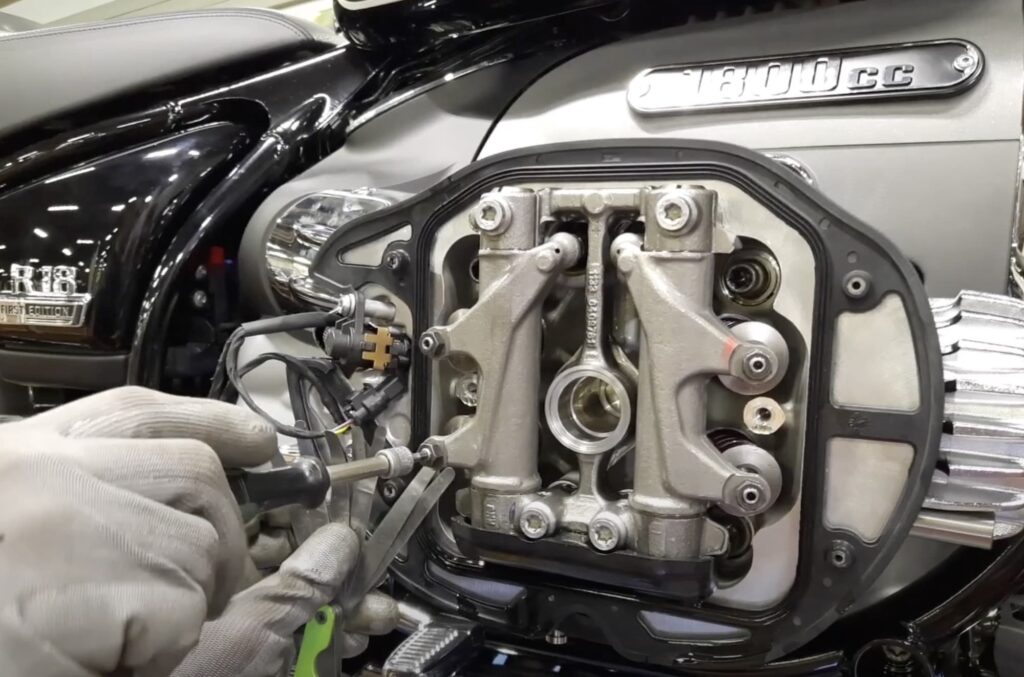

Even though BMW released it more recently than the latest ShiftCam motor, the BMW Big Boxer is decidedly old-school in design. It has four valves per cylinder, but they’re pushrod-actuated, and have screw-and-locknut type adjusters, just like on the 1150 Oilhead motor nearly two decades prior.

And of course, the Big Boxer lacks liquid cooling. It’s a huge lump of metal (over 110 kg!) with an aggressive number of fins to try to dispel that heat.

Because the BMW Big Boxer powers a heritage motorcycle, the R 18, I doubt it’ll get technical innovations like liquid cooling or variable valve timing.

BMW Flying Brick engines (1983 – 2016)

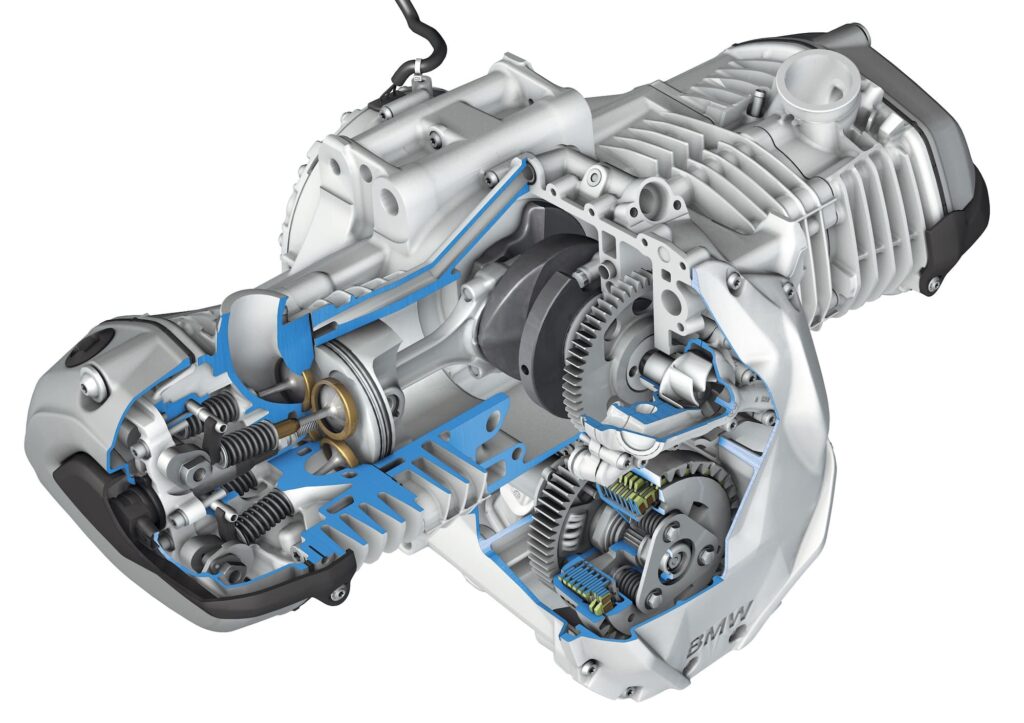

The “flying brick” (German: Fliegender Ziegelstein, thanks to a reader who helped me with the official colloquial translation) BMW motorcycle engine is/was a longitudinally-mounted water-cooled inline 3- or 4-cylinder motor first introduced in 1983, and in the US in 1984.

The first Flying Brick BMW motorcycle engine also launched what’s now known as the K-bikes, a now-extinct line of motorcycles that ended with the K 1300 R in 2016. The first K-bikes were the contemporaneously launched K 100 and the K 100 RS, launched in 1982 (1983 model year).

The K-bikes revolution at the time because it was a liquid-cooled, four-cylinder, fuel-injected engine. It was massively ahead of its time, with a 987cc engine that was horizontally mounted – heads on one side of the bike, and crank on the other.

This horizontally opposed design meant that K-bikes kept the interesting quirk of boxer motors in that revving the engine at a standstill would cause the bike to gently kick to one side. This is known as “character”.

Also, it looked cool. The fact that you could see that “brick” in the middle of the motorcycle is what gave the Flying Bricks their name.

BMW introduced the smaller 3-cylinder K75 (basically a K100 with a cylinder lopped off). And then succeeding the K 100 was the K 1100 RS and RT. It was covered in plastic, usually, so people these days usually buy them and convert them to cafe racers. (It’s a thing with old BMWs…)

In case you’re wondering whether they were called “Flying Bricks” because they could go fast… yes, yes they could, especially with good aerodynamics!

A quick word on the K1: It doesn’t look good now, and it didn’t look good back then. It’s not even a matter of taste, it’s a matter of whether you like garish and ugly things because they’re interesting. MCN’s Andy Downes describes how people react to his K1, which he bought new three decades ago:

There are generally two reactions when people discover I’ve bought a BMW K1. The first is incredulity combined with puzzlement, which often borders on horror. The second is a nodding look of approval; mixed in with a bit of the aforementioned shock. This is much less frequent.

Andy Downes, Motorcycle News

When my wife saw a picture of the bike I was planning to see, she described it as ‘revolting’. However, when she saw it in the metal for the first time she changed her mind, explaining it was “even more horrible than in the pictures”. I sense she is warming to it.

All K bikes up until the K 1200 LT (ending in 2007) had a “Flying Brick” engine. I had a 2002 BMW K 1200 RS briefly with a variant on the horizontal motor (1171cc, 97 kW/130 hp, 285kg/628 lb wet weight).

The BMW K 1200 RS was a fine bike and I really enjoyed the sport-touring position but I didn’t really like it overall. I rented it out a couple of times and then sold it for a tiny profit to a couple who looked like they were about to ride it around the world.

The K 1200 S (the sportier model), however, did not keep the horizontal engine placement, and mounted its engine transversely, like the later K 1300 S. Nor did the K 1200 R, the naked one. But they stayed BMW, and did something non-traditional with the transversely-mounted inline-four and leaned it forward significantly.

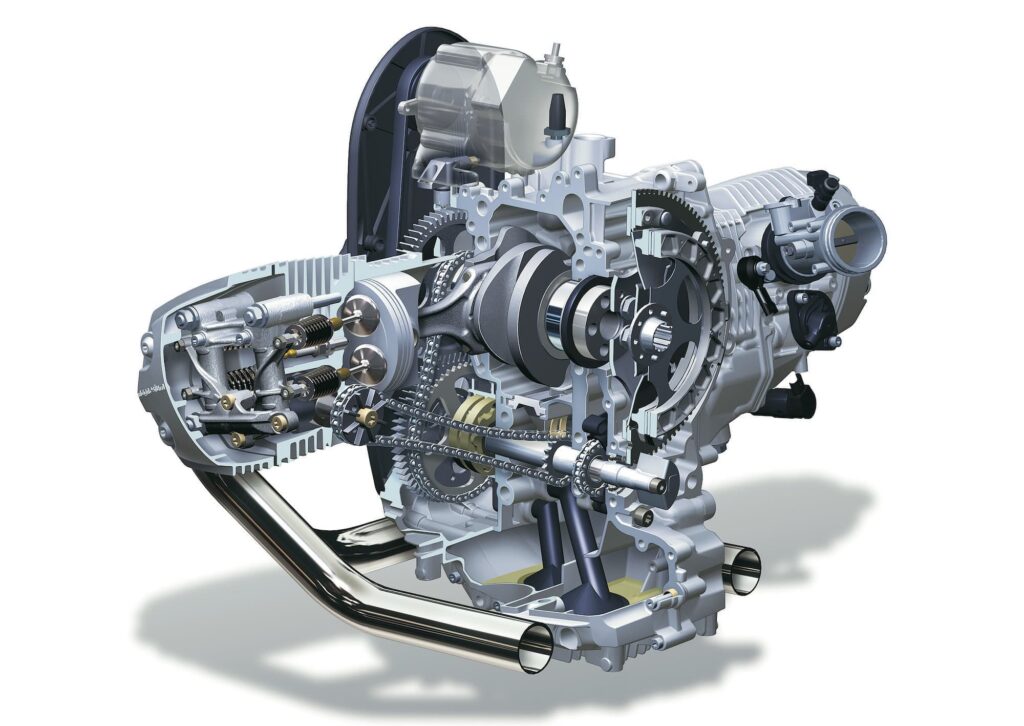

BMW K Slant-4 or Wedge-K engines

The “Slant-4” engine is a laterally mounted inline 4 slanted 55 degrees forward. The reasons for this were: BMW.

Well also, they said that it helped keep weight lower and forward and thus prevent unintentional power wheelies. I guess you need that because this motor makes 140 Nm (100 ft-lb) of torque, which is more than a Harley-Davidson Dyna (though also higher up in the rev range), and 129 kW (173 hp).

By the way, the “Slant-4” name isn’t unique to BMW motorcycles. Some BMW cars also have engines that are canted forward to make sure they fit under a low bonnet.

The Slant-4 BMW motorcycle engine was used in the K 1200 and K 1300 S, R, and GT models since 2006, all the way up to when they were wound up in 2016.

The Slant-4 engine was also the first BMW engine to use a combined engine and transmission case and a multi-plate wet clutch.

Other BMW motorcycle engines not mentioned

“Hey, what about my engine!!” you cry. I’m sorry! I can’t include them all! The above is a history of what I think are the two most significant families of BMW motorcycle engines — the R engines and the K engines.

But that’s not to say the other motorcycles — the thumpers, the parallel twins, etc. — aren’t great. I quite enjoyed the F 900 XR. It’s just that those bikes don’t have their own independent legions of fans, foaming-at-the-mouth rivalries, and so on.

A reader wrote in to tell me that I forgot his first bike, a BMW R26, which he got on his 18th birthday in 1960. Just one example of a BMW engine class I had never heard of — A single-cylinder air-cooled engine with 2 overhead valves that are pushrod-operated. Shaft final drive, too. Awesome!

Nobody is saying the BMW S 1000 RR isn’t one of the greatest bikes of all time — I think history has already been pretty clear on that front! But feel free to leave a comment saying how great it is. It has already been used in a few engines and started to evolve (with ShiftCam in the 2019+ S 1000 RR) so it may be the basis for a whole new generation of BMW motorcycles.

For now though, it seems like boxers aren’t going anywhere.

An entertaining exposition. I’ll make the following observations:

– In the early part of the text, you omit the K75 when referring to Brick engine capacities.

– The F series of parallel twins has a 360 degree crank rather than 180.

– You state the Wethead has two spark plugs per cylinder like it’s predecessors – it has one.

Pz

Thanks, I thought I made those corrections previously. I made them again.

Thank your for the entertaining article.

As a 2013 Camhead R1200R rider, I just want to point out that in the article the image used for the caption of a 2012 R1200R Camhead is in fact a Hexhead.

My oversight, thanks, updated it with the correct photo.

I did not see a 2005 R1200RT? Is it a hexhead?

Yep, those are hexheads.

Hi Hoosh. As a first time reader I (1) take great pleasure in your style of writing and (2) am freely happy to accept any and all technical (or other) “mistakes” that may be pointed out by those more un-ignorant folk amongst us.

Be that as it may… (moving swiftly along)… I am currently the proud owner of a 2019 F750GS (previously a 2017 F700GS).

However, I am about the pull the plug on a VERY LOW KM (44,000) 2010 1200GS priced @ ZAR 125,000(approx USD 8,000).

What can you tell me about my soon-to-be-purchase, ‘afore it’s too late?

What should I look out for?

Appreciated!!!

I wish you emailed me as sometimes I get to replying to comments very late! I don’t know about the pricing, but I think those air/oil-cooled GS bikes are great. I was looking for one, didn’t find one, and ended up with my R nineT (same engine) as a result.

Having owned several oil heads/cam heads etc I can safely say that the new wet head is a huge improvement. Although the previous bikes had about 110 Hp I was always hesitant to use or even find that power simply because at 5000 rpm’s all of them became quite buzzy. That feature may be fine for passing it got annoying after awhile. The wet head pulls well at 4000 rpm at which point the bike is super smooth. In fact it ain’t bad at 5000rpm. What this means is that the bike is in its power and over a larger range. The larger engine could account for some of that but I suspect the tighter tolerances of the partially liquid cooled engine is the bigger factor. I owned a cam head r1200r in 2014 but never a 1200 wet head so I can’t for sure say it’s because of a larger engine.

That being said the 1250 is one of rthe smoothest engines I have owned. Similar in character to Triumph triples before they insisted on making their triples act like twins for the new 900 Tiger.

Totally agree, revving out the stock twin cam is unsatisfying, and 3-6000 rpm is its happy place. Torque starts to drop off at 7 anyway per most dyno sheets. I wonder if a tune and exhaust would make it feel different, but from what I read, if I want to enjoy the 6-9000 rpm band, I should be looking at other bikes (which is why I keep my sport bike).

A 1250 would be nice but that would be a “one bike” budget for me!

Loved this article, great to have a lot of information succinctly in one place!

When it comes to its design, a BMW bike is supposed to be an extension of your personality.

Hear is my story, I am looking to purchase a K75 1995 with a side car for a trip up to ALASKA thru CANADA and back. My concern if there should be one is this bike capable of making this trip and should there be anything to be concerned with. Thanks I hope to hear from you.

Sounds like a fun adventure. I don’t see why not, but I’d definitely take my toolkit and spares with me! A lot of BMW adventurers have done distance on their models. I think it’d be more up to the way you prepare for the trip and your patience level than the bike itself.

Hi Kenneth,

That’s a great bike. There is tons of information about the old K bikes online.

An interesting video is Fortnine’s youtube video on the Flying Brick.

I recently sold an ’87 K100RS that I owned for almost 13 years. It was by far my longest owned motorcycle. Although very dependable, the achille’s heel of those bikes is the final drive splines. If they weren’t maintained properly, they could be worn and fail unexpectedly. It’s one of those problems that would be hard to fix on the road. It’s very easy to remove the driveshaft to check. Mine was toast when I bought the bike.

Safe travels!!

Patrick