If you’re into sporty V-twin motorcycles, but you want something with a little less frequent service requirements than an Italian machine, then you might find yourself looking at something from Honda or Suzuki. From the Suzuki stable, you’d be looking at the Suzuki TL1000S or Suzuki TL1000R.

The Suzuki TL1000S and R are increasingly collectible motorcycles. The TL1000S came at that rare point in history of the late nineties/early to mid-2000s after liquid cooling and fuel injection, but before extreme power, rider aids, and (even more) emissions restrictions.

So the Suzuki TL1000S and TL1000R are decent performers with reliable, low-maintenance engines, that don’t need to be tamed with electronics to help them stay legal (and help you stay alive). This makes them fun to ride and easy to own, especially off public roads where safety equipment isn’t as critical on mid-powered machines.

Luckily for us, we’re all still alive in this glorious period of motorcycling history, and you can still buy these motorcycles second-hand. But if you’re looking at a Suzuki TL1000S or TL1000R you might be a bit confused, thinking:

- What is so special about the Suzuki TL1000S or TL1000R, anyway?

- What’s the difference between the TL1000S and TL1000R?

- What’s all this about a rotary damper? Is it that bad? Is this why they call the TLS the “Widowmaker”?

- Did Suzuki abandon V-twins? (Not likely!)

- What alternatives are out there?

Here’s everything you might want to know.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

Context for the Suzuki TL1000S and TL1000R: A Brief History

For those of you with teeth long enough to bite back into the nineties, you might remember that V-twin sport bikes used to be kind of a big deal.

In fact, that was their heyday. Ducati launched the 916 Superbike and promptly completely stole the show both on track and in showrooms. To date, I don’t think there has been as universally loved sportbike since — so many people from all over the motorcycling spectrum agree that it’s good looking and a good ride, if your back can take the punishment.

The Ducati 916 is, as all Ducatis were at the time, powered by an L-twin, or V-twin slightly canted forwards. The Ducati 916’s engine has desmodromic valve timing, which means that camshafts both open and close the valves, unlike on most other motorcycles in which a cam opens the valves, but a spring closes them. Ducati said this was to help the valves work reliably at high rpm without valve float, but other manufacturers seemed to cope just fine. On top of a desmodromic valve system, the Ducati 916 has — like all other superbikes until the Panigale era — belt-driven camshafts.

See here for more about desmodromic valves.

But unlike the more sedate engines in the Monster and Supersport of the time, which are air/oil-cooled and have two valves per cylinder, the Ducati 916 Superbike’s motor has liquid cooling and four valves per cylinder. This helps the Ducati 916 rev higher and breathe easier, and thus make more power up top.

So there’s good and bad with the Ducati 916, even just looking at the engine. The good is that it’s torque-rich and full of character, with enough top-end to make it sporty. The other V-twins of the day before it couldn’t touch it. Moto Guzzi has mostly made more laid-back cruisier engines rather than high-end sportbikes. Aprilia wasn’t even making big engines yet — and their first one (the 1998 Aprilia RSV Mille) had an engine made by Rotax. And there were Buell bikes around, with (at the time) worked Harley-Davidson motors, but they suffer from typical classic Harley-Davidson reliability, with the added stress of being flung around tracks. Fun while it lasts, though.

And the bad part of the Ducati 916 is the maintenance — 6000 mile / 10000 km service intervals, at which point you have to service the valves (with twice the clearances, as it’s a desmo motor!), and belt-driven camshafts whose belts need tensioning and replacing quite often.

OK, so V-twins ruled, and nobody else had them. What was everyone else going to do? Build their own, of course. Honda released its VTR1000-SP (a.k.a. RC51) superbike, Aprilia decided to throw their hat in the ring with the RSV Mille, and Suzuki released the TL1000S and TL1000R. But there’s much more to the Suzuki motorcycles than just the motor.

Brief introduction to the Suzuki TL1000S

Suzuki announced the TL1000S first in 1997 for the 1998 model year.

On paper, it was a pretty awesome proposition. A sport bike with a liquid-cooled fuel-injected V-twin engine that made loads of power (Cycle World measured 111.5 hp at 9000 rpm, compared to the Ducati 916’s 104.3 bhp), high-end suspension, an attractive trellis frame, and even a back torque limiter clutch. Pretty cool.

When the Suzuki TL1000S stormed onto the scene, people obviously knew it was there to compete with Ducati. It’s not a clone, though. The visual and mechanical design had enough similarities for people to guess that it was inspired by Ducati, but enough differences for it to be obvious that it’s not a copy.

Ducati themselves seemed only vaguely worried. The then owner of Cagiva, Ducati’s parent company, Claudio Castiglioni, seemingly sarcastically welcomed competition, even from motorcycles that are “… very similar to those that have already existed in the market for a long time.” And the then PR manager of Ducati North America, Bruce Fairey, said he hoped that “the TL will take away more GSX-R sales than Ducati sales.”

Early reports about the Suzuki TL1000S were glowing. But something weird happened shortly after the TL1000S was released: It started to develop a reputation for unpredictable behaviour and “tank slappers”. One day, it ended in high-profile tragedy, when a journalist by the name of Simon Carolan-Evans crashed and passed away after such a tank slapper — with his own wife on a trailing bike watching the whole thing. Really a sad story! From this moment, the Suzuki TL1000S got a reputation as a “widowmaker”.

The Suzuki TL1000S wasn’t the first to get this reputation. Over the prior ten years, a number of Japanese manufacturers had built motorcycles that people thought had excellent engines, but which were built around heavy chasses and questionable ride gear that couldn’t keep up. (This was in part why Bimota came about, putting Japanese and other motorcycle engines into their own chasses.)

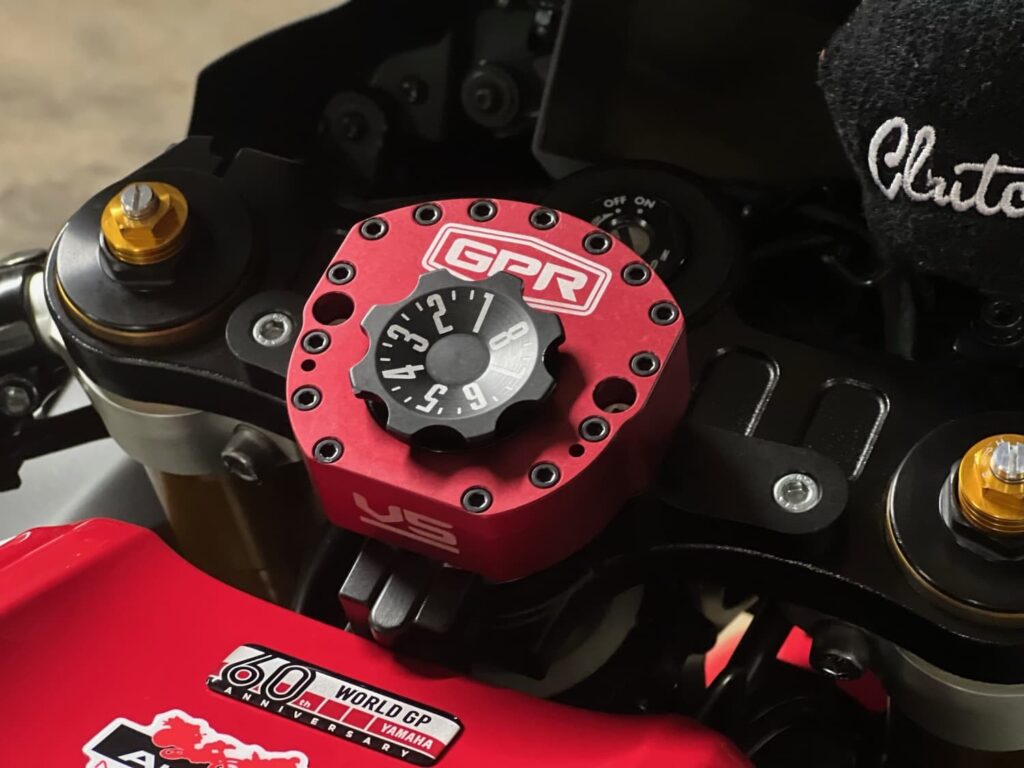

Suzuki issued a world-wide recall for the TLS and installed a steering damper, which became standard fit on later year models. It alleviated the problem, but also neutered the handling.

And by the way, not everyone reported the difficult handling of the TL1000S. Cycle World said of the TL1000S that “There’s little trace of the GSX-R750’s headshake” and that the rear shock “feels like an ordinary damper”.

And others said that the issue of wild behaviour was the combination of a few factors, including snatchy fuelling, the power delivery of a high-compression V-twin, and even including incorrect chain adjustment.

“The swingarm was not the most rigid, and when the rear wheel spindle was loosened,

Practical Sportbikes, 1999

its lugs moved outwards. Owners would adjust their chains, not realising that when they retightened the spindle, the swingarm ends came back in, effectively lengthening

the arm and making the chain too tight. This meant the suspension could not operate correctly. All this was exacerbated by over-sprung forks with too little travel.”

From 1998, Suzuki made some changes to counter the bad initial impression they made with the TL1000S. Suzuki added the steering damper that was added to the recalled 1997 bikes and issued a new ECU which came with a new tune, retarding the ignition in the first three gears and also reducing peak power from 125 to 110. Some suspect it was to make the TL1000R seem faster in comparison. But to me, the Suzuki explanation makes more sense.

If you want to know whether your ECU is one of the low-power ones, look on it for its product code. Unrestricted bikes have ’00’ as the last two digits on the ECU, and restricted ones have ’01’. If you want to remove the restriction, an aftermarket tune should do it.

Look at that yellow thing! Like yellow too? Have a look at my huge gallery of yellow motorcycles here.

Once a bike earns a reputation, it’s hard to shake it. But does the TLS really deserve to be known as a “widowmaker”?

Any motorcycling accident is sad. I don’t mean to devalue that. But the history since the early days of the TLS does seem to imply that while the TL1000 is an unruly motorcycle, it’s not one with an unreasonably high chance of sending you to an early grave.

As many denizens of the TL forums have mentioned: If it were a widowmaker, those boards would be empty.

So in my unsolicited, non-authoritative, non-statistical opinion… no, the Suzuki TL1000S is no more a widowmaker than any other modestly high-power, high-torque, short-wheelbase sport motorcycle.

Put a lot of torque and a short wheelbase into the wrong hands, or even in the right hands with one or two things adjusted poorly, or even everything ideal but a single external circumstance wrong, and you’ll have an accident.

The TL1000S, like many sportbikes of the era, had a lot of power with essentially no rider aids. It has a short wheelbase and suspension that doesn’t respond in exactly the same way as other motorcycles.

This means that if you are riding a relatively predictable and easy to ride motorcycle (say something like an early Honda FireBlade), and jump on to a Suzuki TL1000S or R, you might be in for a shock. (No pun intended, I promise!)

But I’ve found the same when switching between “easy” motorcycles and other difficult-to-manage machines, like my Ducati 1098S Superbike. The Ducati made me question whether I even knew how to ride, and so I went back to school. The riding instructor said that in his opinion, that was one of the hardest bikes to ride on the road. (I don’t think he was just being nice… but anyway, even if that were the case, it’s definitely harder than a lot of other bikes with similar power and weight characteristics.)

Long story short: The TL1000S shouldn’t be written off as a death trap. Just expect to have to adjust to it.

The bonus is that the “widowmaker” moniker puts off superficial buyers, and keeps the market small and tight for people who can see past the noise and know what the Suzuki TL1000 is. If you know, you know!

Suzuki TL1000S vs TL1000R: What are the differences?

OK, so you’ve heard a TL1000 is the bee’s knees. Some people say the better bike is the TL1000S, and some say it’s the TL1000R. Which will it be? It’s a little hard to figure out the differences side by side… so I’m laying it out for you here.

To anyone deep in Suzuki TL world, the answer is obvious. They’re two very different bikes, and they’re surprised when people ask. But to an outsider, looking at two machines that are powered by liquid-cooled V-twins of the same capacity and which have names that are six out of seven letters the same… it’s a very reasonable question!

The Suzuki TL1000S is a bikini fairing-equipped road bike, with the same basic engine as the TL1000R but in lower tune, around a tubular trellis frame, similar to the “curvy” era of SV650.

The TL1000S makes slightly less peak power than the R, but weighs a lot less, has styling that has aged better (other than in a “retro” sense), and compares favourably to other road bikes.

The Suzuki TL1000R is a full-fairing race bike, with a higher-spec, higher-power engine, and higher-grade suspension and brake components, wrapped around a twin spar frame.

But the R is also heavier, and it isn’t as aesthetically pleasing to many (though I like it more, because I like retro angles). Also, the high-swept mufflers can tend to roast your behind, which is usually a con, other than on cold days.

The riding position on the Suzuki TL1000R is more aggressive, though not by a massive degree — they’re both “sporty”.

Below are the specs in detail.

| Model | Suzuki TL1000S | Suzuki TL1000R |

|---|---|---|

| Engine | 996cc DOHC 8-valve liquid-cooled V-twin | 996cc DOHC 8-valve liquid-cooled V-twin |

| Bore / Stroke (mm) | 98.0 x 66.0 | 98.0 x 66.0 |

| Power (dyno, CW / Motorcyclist) | 93 kW / 125 hp – claimed 111.5 hp @ 9000 rpm (CW) | 99 kW / 135 hp – claimed 121.1 hp @ 9000 rpm (M) |

| Torque (Dyno, CW / Motorcyclist) | 71.7 lb-ft @ 8000 rpm (CW) | 74.9 lb-ft @ 7250 rpm (M) |

| Compression ratio | 11.3:1 | 11.7:1 |

| Pistons | Cast | Forged |

| Injectors | Single | Twin |

| Frame | Tubular aluminium trellis | Aluminium twin spar |

| Fairing | Bikini / half | Full |

| Steering damper | No initially; Yes (post-recall) | Yes |

| Front brakes | 320mm discs, 4-piston calipers | 320mm discs, 6-piston calipers |

| Rear tire | 180/60-17 | 190/50-17 |

| Kerb weight | 213 kg / 469 lb | 229 kg / 505 lb wet |

The Enduring Legacy of the Suzuki TL1000’s V-twin Engine

When Suzuki introduced the liquid-cooled V-twin in the TL1000S, it was all-new for Suzuki. They had V-twins previously, but this was the most aggressive one to date.

So it’s no surprise that the descendants of the same motor live on today, though in different guise. Long live V-twins! (They won’t be around much longer, as parallel twins are eating their lunch.)

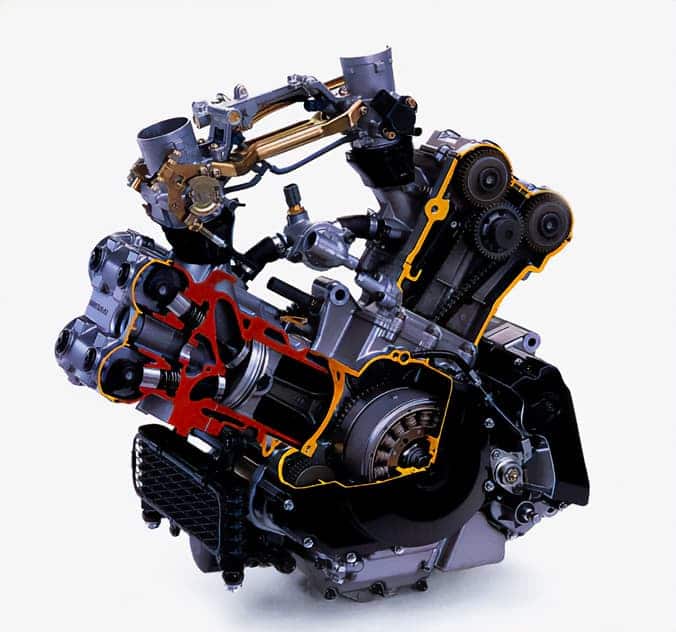

The Suzuki TL1000’s motor is interesting. Suzuki made special efforts to keep it compact longitudinally, as mentioned above.

The primary way in which they did this was the camshaft drive mechanism. Generally, overhead cams are driven in a number of ways, including chains (most motorcycles), belts (mostly some Ducati motorcycles), gears (some older motorcycles), and bevel gears (retro motorcycles or older ones).

All of them have pros and cons, mostly to do with how they deal with heat as the engine warms up, and also how long they last before needing adjusting or replacement.

Suzuki however opted for a combination of a chain and gears. In the Suzuki TL1000 motor, the gear at the crankshaft drives a chain, which reaches a top gear, which then drives the two camshafts via gears.

The advantage of this is that the gears on the camshaft can be smaller. See the image above. If the intermediary gear weren’t used, the camshaft gears would have to be that size.

It may not seem like much, but it brings the cylinder head in 1 cm / 0.4 inches closer. Every bit counts!

Another benefit of this layout is that you don’t have to disturb the cam chains to access the valves when it’s time for a valve service. This means you avoid removing more bits and also avoid the risk of accidentally botching the timin when you re-install the cams.

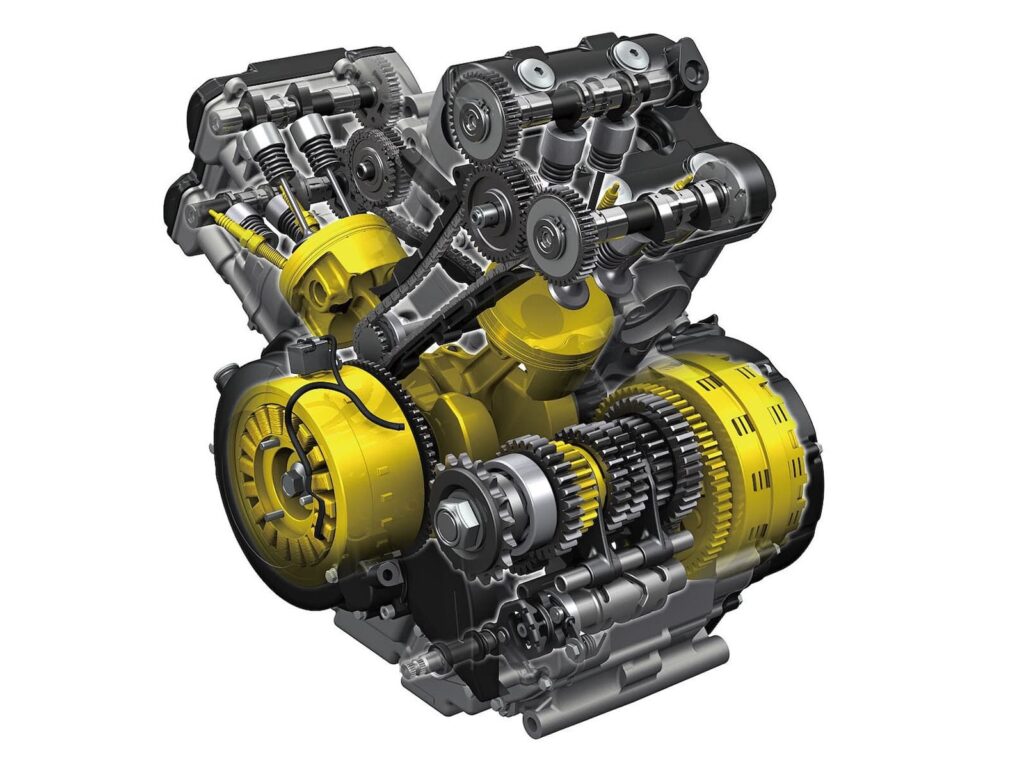

Other Suzuki Motorcycles with the TL1000 V-Twin

The Suzuki TL1000’s engine has lived on past the TL1000S and TL1000R.

First, Suzuki used a mid-tune version of the Suzuki TL1000S’s engine in the Suzuki SV1000. The SV1000 was a bit of a confusing bike for Suzuki, in that it was a mid-spec sport bike not clearly intended for either the track or the street.

Still, it has a beautiful motor with a wonderful roar to it that’s really easy to let loose on! These days, they’re pretty low in price, mostly because they aren’t really the best of anything (and not even the “most classic”). So for the right price, they’re a right lark.

See more about the Suzuki SV1000 here.

Secondly, the engine lived on in the Suzuki V-Strom 1000. Of course, they detuned it for even more midrange torque (which was not lacking) and less top-end. At first, Suzuki kept the 996 capacity motor in the V-Strom 1000, but for the 2014 model of the V-Strom 1000 (still by that name), Suzuki bored the cylinders out by 2 mm to 100 (up from 98), giving the motorcycle 1037 cc of capacity.

Suzuki finally updated the name to “V-Strom 1050”, but kept the same engine dimensions. The modern bike, the V-Strom 1050DE, still uses the 1037 cc motor.

Here’s a quick gallery of the various Suzuki motorcycles with the Suzuki TL1000-derived engine below.

Non-Suzuki Motorcycles with the Suzuki TL1000 V-Twin

But wait, there’s more! The Suzuki TL1000’s engine’s story doesn’t even end with Suzuki.

The Suzuki TL1000 V-twin was such a stomper that even the Italians wanted a piece of the action. Cagiva used the motor in the Cagiva Raptor 1000, a naked sport bike.

Cagiva also used the same motor in other Raptor variants with more modern styling. But man, the Raptor 1000 is a looker — like a modern SV650 (which is pretty handsome, even if it’s an affordable bike) but with a lot more muscle. And the Raptor has inverted forks, big calipers, and so on. (Cagiva also made a smaller Raptor with the SV650’s motor. It’s also very cool.)

Another Italian outfit, Bimota, fit the Suzuki TL1000’s engine into its own sport bike, the SB8K.

Bimota made a few variants of the SB8 motorcycle, with some specs including things like Öhlins suspension, forged wheels, carbon fibre bodywork, different fuel injection systems, and so on. They’re all exclusive, hard to find, super cool, and way out of my budget, so if it’s OK I’ll stop looking at them!

Of course, the TL1000 motor is not the only one that Bimota used in its motorcycles. Bimota have built custom motorcycles around other Japanese manufacturers’ motors, as well as around Ducati ones.

Still, the fact that there are super-exclusive and high-spec Bimota motorcycles with a Suzuki motor speaks volumes about how good Suzuki TL1000R’s motor is.

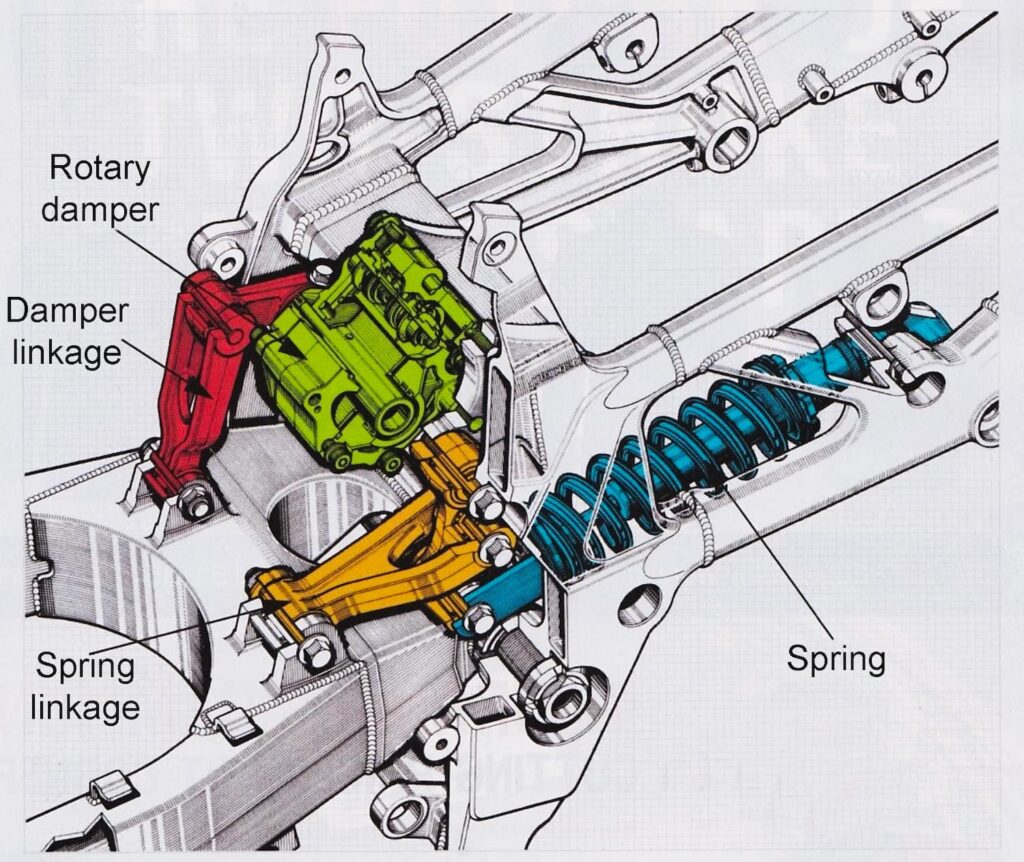

The Suzuki TL1000 Rotary Rear Damper

One controversial bit of kit in the Suzuki TL1000S and R is the “rotary rear damper”. This is a bit of a long story because I’m trying to answer every question.

Let’s clarify up some terminology first. A shock absorber, usually called a “shock” or sometimes an “RSU” (rear suspension unit), is made of a spring as well as a damper in one unit. The damper is oil that is forced (usually by a piston) through valves, and that motion slows the movement down, much like how when you wave your hand through water it is harder than when you wave it through air.

By the way, damper and dampener are closely related words; some people get persnickety over definitions, but they’re effectively interchangeable. Cambridge dictionary defines them as synonyms, but gives slightly different examples. Sometimes one word can sound more “right” in certain situations, but context makes it clear what we’re talking about, and it doesn’t impede communication to use the other word.

Though “dampener” can also mean to make something more “damp”, as in “wet”. And in Australia, “damper” is a kind of campfire bread, which isn’t soggy at all. Context definitely makes it clear whether we’re talking about suspension design or bread!

In well-designed suspension, a spring and damper are tuned together so that the energy dissipates quickly and effectively, without bouncing around out of control, or being too harsh.

In most motorcycles, the rear suspension is one unit. You’re probably familiar with what a rear suspension unit looks like… unless you ride hardtail Harleys with no rear suspension, or if you ride Softails with a hidden rear shock!

On the Suzuki TL1000S and TL1000R, the rear suspension is split into a spring on the right and the damper on the left. The damper on the left is the rotary rear damper we’re talking about. But really, criticising the rear suspension of the TL is to criticise the whole design.

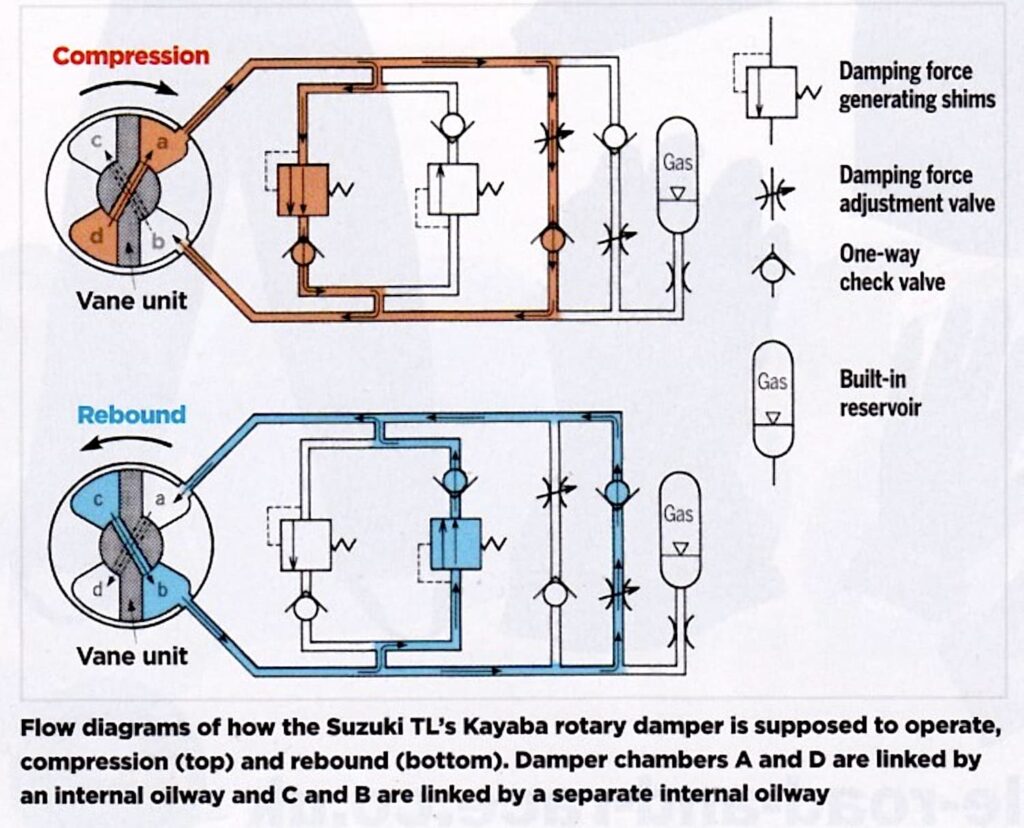

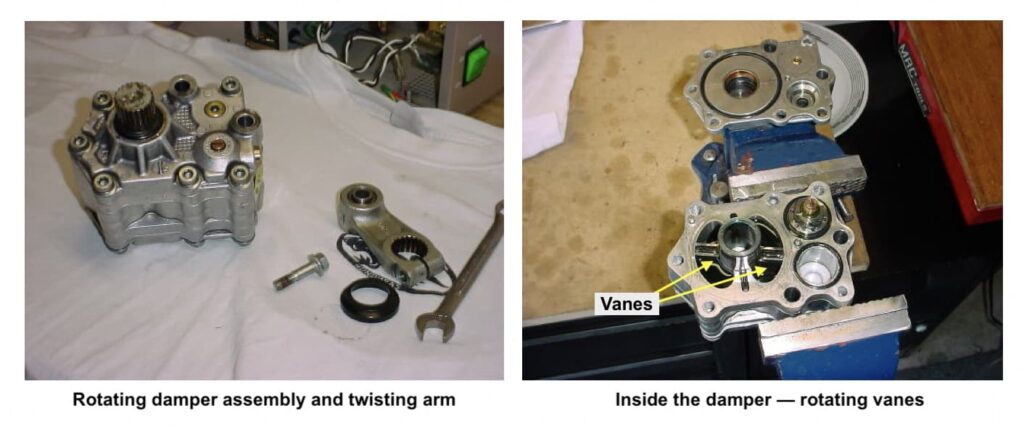

The rotary rear damper works via an arm with a joint. As the rear wheel moves up and down relative to the chassis, it twists the rotary damper, which provides a damping function — same as in a linear one, but in a rotating motion. Neat! Here’s how it looks in practice.

The rotary damper works with the same principle the damper in a normal shock (which combines the spring movement and damping), but with a different movement style. Like any normal shock absorber’s damping function, the oil absorbs the movement.

But the difference, of course, is that there’s no longitudinal sliding movement like on a normal shock. It’s rotational. Inside the Suzuki TL1000’s rotary rear damper, there are rotating vanes.

As the vanes travel around, they force oil through the rebound and compression valves and washer stacks, just like in a normal shock absorber.

There’s a small, pressurised gas chamber to compensate for the thermal expansion of the oil as it heats up.

The rotating damper means that there’s no shear force against the sides of the shock as the suspension travels up and down. This makes for less stiction, and in theory, more efficiency.

Why Use a Rotary Rear Damper?

So why do this? It seems weird and complicated; perhaps unnecessarily so.

Suzuki’s primary reasoning behind the rotary rear damper was to save space and keep the wheelbase short. The shorter a motorcycle is, the more weight over the front tire (to a limit), thus front tire traction, and the easier it is to handle when accelerating and cornering.

The problem with liquid-cooled V-twins is that they’re long. The engine itself is long, and then there’s the radiator at the front.

Other manufacturers fix this in different ways. Honda put the FireStorm’s radiators on the side rather than the front. Ducati cants the engine forwards — which is why we know them as the “L twin”.

Suzuki did use some innovations in the Suzuki TL1000’s engine, by packaging the cam gears and camshafts more compactly, as mentioned above.

But aside from engine modifications, Suzuki also decided to attack the problem from the rear end, by building a more compact rear suspension unit.

There are some other advantages to Suzuki’s rotary damper setup.

Suzuki was hoping that the aluminium body of the rotary damper would be better at dissipating heat. Testers said that after track sessions, the damper would remain cool to the touch (see this 1997 test on motorcycle.com).

Also, the rotary damper is overall a lower energy unit, so it produces less heat overall. Because it depends on a rotating motion rather than a telescoping one, you can use roller bearings rather than bushings. This makes for no exposed sliding surfaces — and no chance of dirt and oil being forced into the shock.

Since the inside of the rotary damper unit isn’t also occupied by a coil spring, in theory the Suzuki TL1000’s damper can pump a lot of oil. This means you can make more fine adjustments to the damping characteristics. As a bonus, it’s quite easy to get to the compression and damping adjustment screws of the TL’s rotary damper, compared to those on many monoshocks.

Finally, having a separate damper from a spring allows for more customisation of damping vs spring ratios.

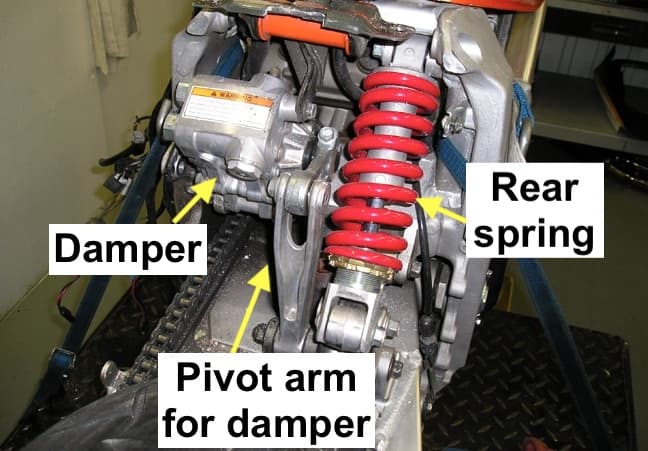

Drawbacks of Suzuki’s Rotary Damper

Rotary dampers are fine. Race teams used them in Formula 1 cars. And they exist elsewhere in the motorcycling world. For example, steering dampers in high-performance sports motorcycles often use a rotary design.

Unfortunately, the Suzuki TL1000’s rotary damper has a number of drawbacks.

Firstly, people complained that the Suzuki’s damper didn’t have enough oil (some ~50cc compared to ~300 cc in most shocks — and it varied widely in the TLs due to loose manufacturing tolerances). Suspension experts (like those at Maxtons in the UK) also say that regardless of the oil content, the vanes in the TL1000’s rotary damper don’t push much oil through the flow restrictors — around a third as much as in a normal damper.

This is fine at normal speeds, but when pushing the motorcycle (and working the suspension unit) the damping fluid would get too hot, and its viscosity would change. It seems that the high volume of pumpable oil and good heat dissipation characteristics didn’t live up to many riders’ expectations.

Secondly, Suzuki’s damper isn’t serviceable. It’s much harder to assemble suspension units that don’t work longitudinally with circular seals, and manufacturing needs much stricter tolerances. The rectangular area between the rotor and damper body are vulnerable to warping. You can of course service anything, and some dedicated folk do, but most professionals don’t touch it.

Finally, the unique rear suspension setup means that you can’t just swap out a shock easily — options are more limited, though they do exist.

Solutions for the TL’s rear suspension

Suzuki initially responded to complaints about the TL1000S’ handling by recalling them to fit a steering damper, which was fitted as standard to the TLR. This was a broad response to handling, and not directly aimed at “fixing” the shock.

Suzuki also relocated the shock slightly in the TLR, moving it further along the swingarm so that it wouldn’t get the heat from the rear cylinder — even though the heat issues were down to the way the damper was designed.

So what do people do? The rear suspension unit is fine, in principle. It has originality value, and it works — especially if you’re not using your Suzuki TL1000S / R at the edge of its performance envelope.

But some people are either unhappy with the performance, spooked by claims of alternatives being better (or safer), or just in search of something different. If that’s you, since the TL has been out for a while now, you can replace the rear unit completely — you remove the shock, and put a combined shock and suspension strut in place of the existing spring.

There are generally three things I see people do to replace the shock:

- Replace the damper with a branded shock and bracket from a manufacturer like Bitubo, Maxtons, or even Öhlins (see Öhlins suspension on Revzilla for example). This is expensive, and as time has gone on and the price of the TL1000S/R has gone down, it isn’t as obvious a fix as it once may have seemed — there are other, faster bikes you can get for less money. So you have to be a TL diehard for it to be a good idea. (Update: A commenter said I forgot to mention Hyperpro suspension, which in their opinion is the best!)

- Get a custom bracket (some of the denizens of TLPlanet / TLZone made and sold them) and a shock from a donor motorcycle, like a mid-2000s Yamaha YZF-R1, without the spring on the shock. This is a budget and apparently an effective fix.

- Rebuild the damper with more and/or different fluid.

Rebuilding might seem the most daunting, but it’s totally possible. It might even be the best course, as brand new aftermarket kits are becoming hard to find for this older motorcycle.

A Brief Word about the TL1000’s Clutch

The Suzuki TL1000 has what Suzuki described as a clutch with a “back-torque limiter”, which many enthusiasts have simplified as a “slipper clutch”.

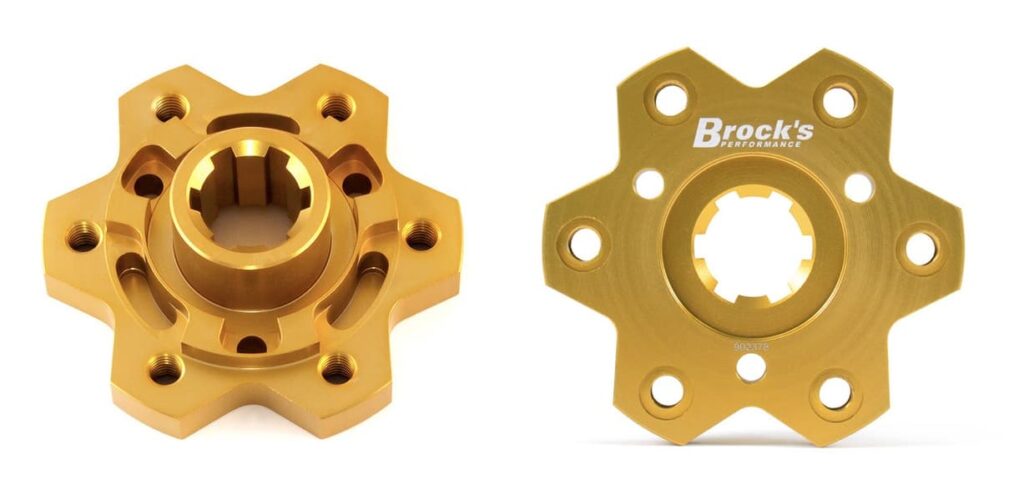

But a few enthusiasts have been pointed out that the TL’s clutch hub — which is the same as on the Gen 1 Hayabusa — is more of a torque-assist clutch. When the rider backs off the throttle, there is minimal pressure on the springs, allowing the clutch to slip. Then, when the rider accelerates, the clutch mechanism pulls back on the springs and applies more preload to the springs for tension to stop it from slipping under power.

In theory it seems like a simpler alternative to a slipper clutch. It does work — or at least it did when it was new. The problem is that as it wears, the TL1000’s back-torque limiter can behave unpredictably, causing slip and lag on acceleration and too much slip on deceleration.

So a common aftermarket modification is to weld the clutch, or to replace the factory back torque limiter with a part from Brocks.

Once you’ve modified the clutch in this way, the clutch does have a heavier pull, but it’s much stronger. You get all the power delivered to the ground with no slip. Buyer beware — this will only add to the Suzuki TL1000’s reputation!

Other Common Modifications for the TL1000S and TL1000R

While the Suzuki TL1000S / TL1000R are obviously perfect as they are, there are a number of modifications that people typically make to them.

Firstly, people modify the suspension, as mentioned above. Even this isn’t mandatory. But many find it rewarding. There’s also the clutch mod mentioned in that section.

But aside from the suspension and clutch, scouring the TLPlanet forums, this is what else people seem to do to the Suzuki TL1000S and TL1000R:

- Remove the steering damper: Even though this was the solution to the TL1000S’ “widowmaker” reputation, not everyone likes the way its feels. So some owners remove it off either the S or R. There are other aftermarket adjustable steering dampers that some prefer.

- Rear tyre swap: The TL1000S comes with a standard 180-profile rear tire, whereas the TL1000R comes with a 190. Some TLR owners like to swap back to a 180 for more agility, and more options, but the fat 190 rear tire does look cool!

- Electrics: Owners seal the front spark plug, as if it gets wet, it can be problematic. I’ve also previously seen this advice for the SV650.

- Brake disc swaps: People swap out the front brake discs and calipers, some opting for the ones from the Hayabusa, which is a direct swap.

Alternatives to the TL1000R

If you’re looking at a V-twin sport bike and aren’t looking at a Ducati, then really there are just two other options: The Aprilia and the Honda.

There’s also the Suzuki SV1000S, which came after the TL1000R. (See more about that above.)

Honda VTR1000 (1997-2005) (of any variety)

Right off the bat, this is going to get confusing, as there are multiple motorcycles that could be a VTR1000, and they all have a plethora of names!

But really there are just two. There’s

- The Honda VTR1000F FireStorm, known as the Super Hawk in the USA. This is more akin to the TL1000S. The logo looks like “FireStorm”, some people write it as Firestorm, and I have no idea what’s correct. Super Hawk seems to always be written that way. This is the street bike, with a lower-tuned (80 kW / 110 hp @ 9000 RPM) carburettor-fed V-twin with a slightly longer stroke engine. Same bore and stroke as the Suzuki TL1000S, actually. It has conventional forks with less adjustability in the suspension, and smaller discs.

- The Honda RC51, otherwise known as the VTR1000SP and VTR1000SP-2, or the RVT1000R. This is more akin to the Suzuki TL1000R (but the Honda is much lighter). The SP-2 had the longer reign, but both are highly sought after and super expensive relative to what you get on paper (aside from brag value). The RC51 has a shorter stroke fuel-injected engine that revs higher and makes considerably more power — 100 kW / 136 hp @ 9500 rpm. It has inverted forks with fully adjustable front and rear suspension, and larger 320 mm discs. It also runs hotter and is more generally hot-blooded. But it did win races.

In terms of how these all compare — well, they’re all great bikes. Go to the TL forums or Super Hawk forums and you’ll find fans of each. Obviously, having any example of any of these bikes tuned to your preferences is probably the best bike for you, and two decades after their reign, I’d focus more on a quality example than any particular model — but I’m less fussy about specific models!

You could say in terms of street bikes, the Suzuki TL1000S is the better bike (despite the “widow-maker” history) than the FireStorm / Super Hawk, as it’s more powerful, fuel injected, and has much higher spec suspension.

But in terms of race bikes, the Honda RC51 is the better bike than the TL1000R as it’s lighter, almost universally acknowledged as better looking, and it actually won the World Superbike Championship in 2000 and 2002.

Aprilia RSV Mille

Aprilia also released its first-gen RSV Mille around the same time, in 1998.

You might think of Aprilia (as I do) as making many high-end sport bikes, including the Tuono V4 and the RSV4, both of which it has now made for over a decade.

But the 1998 Aprilia RSV Mille was actually the first big-displacement sportbike for Aprilia. Up to then, they had only made 250cc motorcycles! Aprilia didn’t make the engine for the Mille, but rather got it made by Austrian company Rotax, who had also made engines for BMW and KTM.

The RSV Mille — and its higher-spec sibling the RSV Mille R (with Öhlins suspension and steering stabiliser and lightweight wheels) is a pretty worthy competitor to Ducati and other V-twin motorcycles. The problem is, over time these bikes have become notorious for wiring and electrical issues. To be fair, many old bikes have, but like I said… notorious!

Luckily you can get newer versions of the RSV Mille, like the RSV1000R and RSV1000R Factory, which have fewer problems (in part just due to not having been around for as long).

Aftermath

The funny thing is that while V-twins had their day, those days are long gone. Both Suzuki and Honda stopped making V-twin powered sportbikes in the mid-2000s. Aprilia shortly afterwards bailed for the V4 and never looked back. And even Ducati now uses a V4 motor in its flagship motorcycles.

So these days, if you want a V-twin powered superbike, your only choice is a Ducati. And even then, you’d be looking at the bikes that — as excellent as they are — aren’t meant to be the cream of the crop, like the Ducati Panigale V2.

So where are we going from here? I don’t think V-twins will be a thing again, especially as the market for gas-powered motorcycles shrinks. So if you want a V-twin from a Japanese manufacturer, something like the TL may be your last chance.

Regarding aftermarked rear suspension, you forgot to mention the best one: Hyperpro…

Wouldn’t normally bother to leave comments for an article but all credit to you, this is a great one for prospective buyers. Just nabbed a 2900 mile TLR myself, looking forward to doing a few mods to it, which is something I never bothered to do with any of the many Ducati I’ve had as they were pretty sorted out of the box.

Thanks CB. I’m exactly the same with comments. So I appreciate it all the more. Congrats on your buy!

Great article.

Good details & tech.

Best regards!

Great article Dana. I haven’t read most of that information before.

A little more on the Buell would have been apropos, the 2008/9 with the Rotax engine.