If you’re a fan of Kawasaki motorcycles, you might have come across the phrase “Sugomi” design”. Generally, Kawasaki uses it to describe their “Z” series motorcycles, starting with the Z1000, including the Z H2 and Z900, and even extending it to the relatively humble Z650.

Japanese speakers may intuitively know what “Sugomi” means, but I didn’t, so I looked it up.

The best way to understand the meaning of “Sugomi” is to look at the Kawasaki Z1000 and think: this machine embodies Sugomi design more than any other.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

Sugomi Design — In a nutshell

In a nutshell, “Sugomi” is a Kawasaki design philosophy that Kawasaki has used since the 2014 model Z1000.

In their literature and in press materials, Kawasaki mentions “Sugomi design” summarily like we’re supposed to know what it is. Even on Kawasaki’s website today you can see this word.

But outside Kawasaki, “Sugomi design” is not an established concept. It’s not akin to, for example, general design or art schools like “art deco”, “minimalism”, and so on.

In a nutshell, Sugomi design could be summarised as meaning “aggressiveness” in styling. It’s a word to describe a Kawasaki design philosophy for their motorcycles.

Looking at the language from which it came, the word “Sugomi” is written in Japanese as 凄み (a Kanji character and a Hiragana character), often just abbreviated to 凄 in graphics.

The Japanese word 凄み translates to “Amazing” via Google Translate. Other dictionaries translate it as “intimidating or threatening”, or even “ghastly” or “weird”. Great, thanks, dictionary…

Chinese readers will recognise the first character as meaning “bitter/cold” or “miserable” in Chinese, pronounced qī in Mandarin. Not a very helpful translation either!

As for how Kawasaki interprets the concept of sugomi in their design language, they describe it as:

- “Awe-inspiring energy and intensity”, like a “predator in a crouching posture, gathering its energy in preparation to strike” (June 2014 Technical Review, referring to the Z1000)

- “A machine with the palpable energy and appearance of a predatory animal stalking its prey.” — Kawasaki UK

- An absence of rider aids such as traction control or ride by wire, which would be “counter to the Sugomi philosophy” — per Kawasaki reps (cited by Cycle World)

So how does “Sugomi design” translate in reality? Let’s see through examples.

Examples of Kawasaki Sugomi design

As I mentioned above, Kawasaki first started using the word “Sugomi” to describe the 2014 Kawasaki Z1000, but has since extended the philosophy to other naked motorcycles.

But you can see the implementation of Sugomi design most easily in the Z1000. To implement Sugomi design on the Z1000, Kawasaki focused on

- Visual aesthetic — How the bike looks

- Handling

- Auditory aesthetic — The sound (primarily of the intake)

Visual aesthetic

In designing the 2014 Kawasaki Z1000, Kawasaki said that to realise the image of Sugomi they had to do a number of things, but they went into a lot of detail in particular in how they changed the front headlamp to make it more aggressive. Principally, they had to make it thinner and smaller.

To make the front headlamp more aggressive, Kawasaki had to implement a small, high-luminosity LED. For this to work, they had to do a number of things, including implement a reflector to properly illuminate the road, attach a radiator to sink heat out of it, then think about how to make the radiator housing small enough so it wouldn’t interfere with steering.

Have a look at the earlier gen Z1000 and compare it with the Sugomi generation to get an idea of how these changes translated to reality.

It’s quite interesting to see how much effort Kawasaki went to just to implement a visual design language, even though it wasn’t the most practical option.

Riding position and handling

On riding position, you can visually see that the 2014+ Z1000 has a more forward leaning riding position. This comes mostly from moving the handlebar position further forward. This is of course not unique to the Z1000.

Kawasaki also improved handling, reducing the un-sprung mass by reducing the weight of the wheels, reducing steering friction loss, optimising the suspension, and implementing Showa SFF-BP, which has a damper only on one side (allowing for lighter weight).

Sound

On sound, many Kawasaki fans know that their bikes have a great intake howl. The Z1000 was one of the pioneers of this trend!

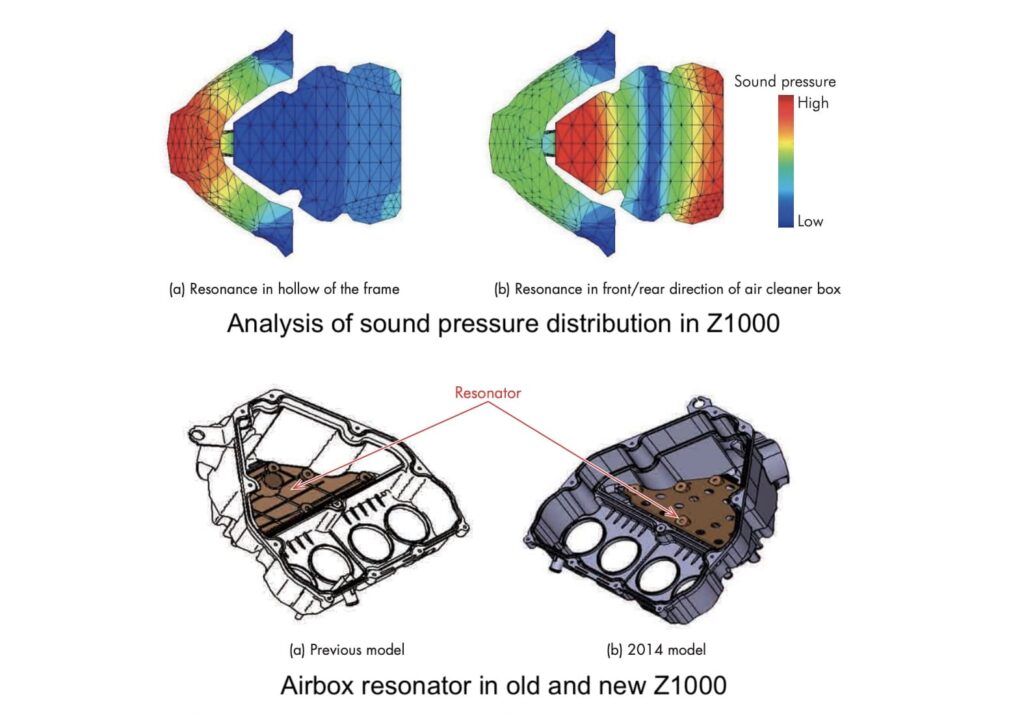

Kawasaki went to great lengths to improve the intake howl, analysing the sound pressure distribution in the frame and air cleaner box, and designing a structure to enhance the note. It’s a bit artificial, but it sounds and thus feels great. What’s more, the degree howl always corresponds to actual power output of the engine.

Many Kawasaki bikes have a great intake sound. Even the Kawasaki Versys 1000, a somewhat pedestrian SUV-like touring bike, has great intake sound. So this aspect of “Sugomi” design seems to have transferred successfully into other motorcycles that don’t even make the claim to have the same design aesthetic.

Lack of Rider Aids

Aside from ABS and an assist & slipper clutch, the final Kawasaki Z1000 did not have any electronic rider aids — no ride-by-wire (and thus no power modes), no traction control, and definitely no inertial measurement unit.

Kawasaki maintained this over the course of the Z1000’s life, through to the present model (which may be the last, as it has been discontinued in some markets in favour of both smaller and larger motorcycles).

Other motorcycles with Sugomi-inspired design (see below), however, do have some rider aids. So this element of the design philosophy has been diluted somewhat.

Other Kawasaki motorcycles with Sugomi design (or Sugomi-inspired design)

In the US, the Kawasaki Z1000 is no longer available. But you can see some aspects of Sugomi design — or what Kawasaki now calls “Sugomi-inspired” design — in other Z bikes.

Kawasaki has used the word “Sugomi” in the marketing of the Z H2, the Z900, and even the humble Z400 and smaller motorcycles, though usually these were billed as “Sugomi-inspired”.

How these are “Sugomi-inspired” is left up to the imagination. Kawasaki doesn’t explicitly tell us. You can see that they have a bit of forward crouch and yes, they look a bit aggressive… but none as much as the Z1000 does.

One thing I’ve noted from riding a few Kawasaki motorcycles is that they do pay attention to the intake note, and I find the factory intake howl on Kawasaki four-cylinder engine motorcycles really pleasing (and I’m not alone in thinking that).

Kawasaki Z1000 and Z800 Sugomi Edition — Not that different

For the 2016 model year, Kawasaki released “Sugomi edition” Z800 and Z1000 models.

These are pretty much identical to regular Z800 and Z1000 models; they’re not fundamentally more Sugomi-inspired than any others. But they DO have a special Akrapovič silencer.

“So what?” you ask. “I can get an Akrapovič end can, too.” Ah, but your Akrapovič silencer won’t be imprinted with a 凄 character… I mean, unless you bung a sticker on, too.

I do wish Kawasaki went further with using the “Sugomi”, character, much like how Suzuki uses the Hayabusa character (隼) on their iconic sportbikes, or how they use the Katana (刀) character on their Katana resurrection.

I’m all for kanji used in design, so I’m hoping the 凄 character makes it onto a body panel somewhere.

Sugomi-esque design elsewhere in the Motorcycle world

Branding aside, “aggressive” design language is absolutely not unique to the modern Kawasaki Z range. The “forward canted, aggressive naked” is also known as a “streetfighter”, and is a factory design philosophy that became very popular in the mid-2000s. (“Actual” streetfighters, loosely sport bikes without fairings, have been around since the first time someone crashed their sport bike and decided to not buy new fairings.)

Below is a non-exhaustive examination of some other motorcycles with aggressive streetfighter designs that came both before and after the Kawasaki Z1000.

Note that the below motorcycles represent the aggressive streetfighter aesthetic in just a visual sense.

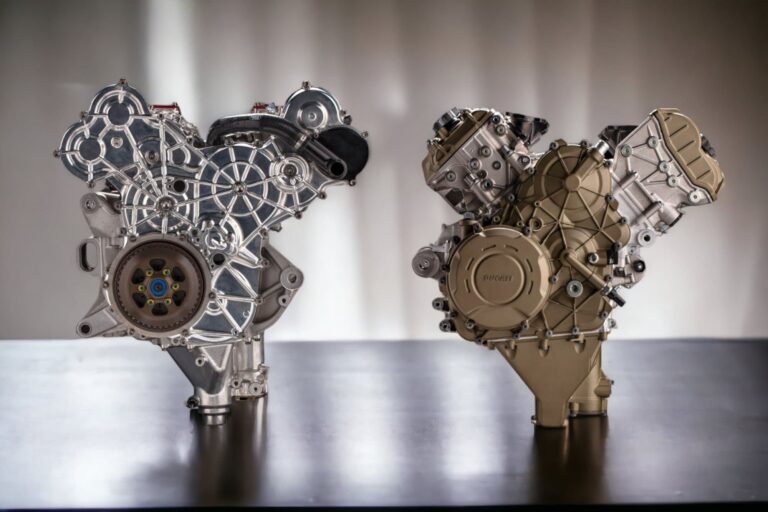

Ducati even began naming motorcycles after the visual design philosophy – the Ducati Streetfighter, and there are definite design commonalities between the Streetfighter and the Sugomi Z1000. Below you can see an image of the Ducati Streetfighter shown in 2008, with the Kawasaki Z1000 Sugomi edition on the right.

See our guide to the history of the Ducati streetfighter.

Red Ducati Streetfighter base model 2016 Kawasaki Z1000 Sugomi Edition

Ducati had also been making sport bikes on naked chasses before that, too. But it’s all a matter of degree, and the aggressiveness in the design really seemed to reach a maximum in the streetfighter.

MV Agusta had been building the “Brutale” streetfighter-style since 2001, and have had an aggressive design since that first version all the way to the modern day.

2022 MV Agusta Brutale 1000 RR Nürburgring 2001 MV Agusta Brutale 750 S Serie Oro

The second-generation Honda CB600F Hornet (non-US) and the first-generation Honda CB1000R, both of which predated the Kawasaki Z1000, also had a few elements of factory Streetfighter design (notably projector headlights).

2007-2013 Honda CB600F Hornet (Europe) 1st gen Honda CB1000R

Post-Z1000, other brands also implemented similar aggressive design elements. Some notable examples are the Yamaha MT-10, and the Suzuki GSX-S1000, especially the 2022+ version.

So what are all these motorcycles? Their various manufacturers don’t call them “Sugomi design”, of course, as that’s a Kawasaki term. They don’t even always call them streetfighters. But they’re just examples of how the concepts that Kawasaki has used in its naked sport bike design aren’t entirely unique.

![Ducati MotoE Electric Motorcycle — What We Know So Far [UPDATED] 27 Ducati MotoE Electric Motorcycle — What We Know So Far [UPDATED]](https://motofomo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ducati-Electric-motorcycle-MotoE-prototype-2021-768x512.jpeg)