Talking about Ducati motorcycles inevitably means mentioning Ducati engine names, so you’re likely to see things like “Desmodue” or “Testastretta 11-degree” and know what it means.

For newcomers to Ducati or any brand with its own unique jargon, these Ducati engine class names can be bewildering. “Desmo”? “Testa”? Are we speaking Italian?? Parla inglese, signore?

Aside from the alien nature of the names, they also imply a whole bunch of stuff that relative beginners to motorcycles may not know off the top of their heads — like valves per cylinder, how the camshafts are driven, and what kinds of bikes they’re likely to be in.

Because writers don’t like to repeat themselves all the time (it’s boring for them as well as for the reader!) they might not go into detail about what these engine types are in every article. So I’m putting down this quick explainer about Ducati engine types so you can know things like:

- The main features of each engine type (valves, timing system, camshaft drive, etc.)

- The genesis of the engine — How it came to be

- Where the name comes from and what it means

- Some motorcycles with the engine

OK, here goes.

Updated Nov 2023 with more details about the Superquadro Mono.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

Ducati Engine Types — Summary Table

Below is a summary of all the Ducati engine types from the last few decades. There are others — single-cylinder engines for example — but those are museum pieces!

One thing to point out is that, although these are names, they aren’t typically Italian words. There are a few exceptions where Ducati adopted an existing word. But don’t be too fearful about mispronouncing them. It’s a bit like pronouncing “Ducati”, or “Ferrari”, or “Öhlins” — you just pronounce it like people around you say it. (But see our pronunciation guide if you want to get a bit closer.)

I’ve boldfaced a few of the notable items below.

| Engine type | First year, bike | Cylinders | Valves per cylinder | Cooling | Cam drive | Valve return | Valve service interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desmodue | 1971, 750 GT | 2 | 2 | Air or Air/oil | Gear, Belt | Desmo | 6-7.5k miles, 12-15k km |

| Desmoquattro | 1987, 851 Superbike | 2 | 4 | Liquid | Belt | Desmo | 6-7.5k miles, 12-15k km |

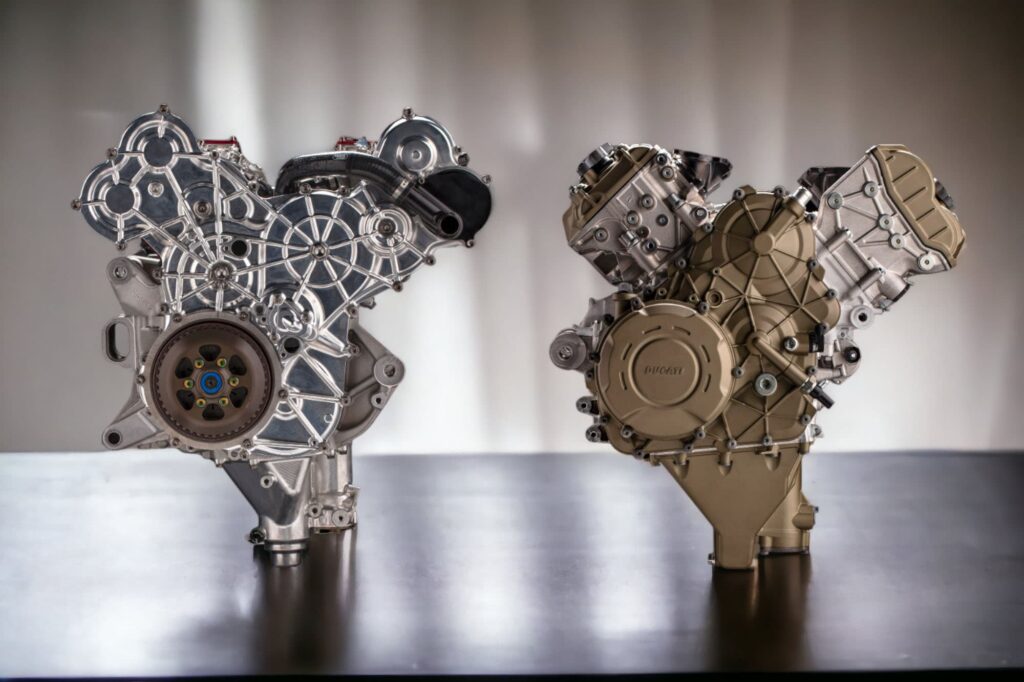

| Desmosedici | 2008, Desmosedici RR | 4 | 4 | Liquid | Gear | Desmo | 7.5k miles / 12k km |

| Testastretta / Evoluzione | 2002, 996R / 998 Superbike | 2 | 4 | Liquid | Belt | Desmo | 7.5k miles / 12k km |

| Testastretta 11-degree (inc DVT) | 2011, Multistrada 1200 | 2 | 4 | Liquid | Belt | Desmo | 18k miles, 30k km |

| Superquadro | 1199 Panigale | 2 | 4 | Liquid | Chain | Desmo | 15k miles, 24k km |

| Desmosedici Stradale | 2017, Panigale V4 | 4 | 4 | Liquid | Chain | Desmo | 15k miles, 24k km |

| V4 Granturismo | 2019, Multistrada V4 | 4 | 4 | Liquid | Chain | Spring | 36K miles / 60K km |

| Superquadro Mono | 2024, Hypermotard 698 | 1 | 4 | Liquid | Chain | Desmo | 18k miles, 30k km |

Nomenclature / Terminology

Here’s a brief note on the nomenclature and terminology used in this article. While some of these terms describe engines in general, others, like “desmodromic”, are specific to Ducati engines.

- L-twin: This is what Ducati calls its V-twin engines that lean forward. While Ducati isn’t unique in this design, they’ve coined it “L-twin”.

- Valves per cylinder: Valves are to let fuel/air mixture into a cylinder, and to let exhaust gas out. Four-stroke motorcycles have at least two valves per cylinder, but many modern ones have four; some older designs had three, and a few had five. I don’t think I’ve heard of any with six or more. More valves means more faster!! But seriously, it does mean more power potential, because you have more control over how the engine breathes, and using timing and other mechanisms you can allow for breathing that optimised for good torque down low and high power up top.

- Cooling systems: “Air cooling” means the engine is just cooled by air flowing over it. “Air cooling” as an umbrella term often also includes bikes that use explicit oil cooling, with oil being funnelled about the engine strategically to pick up heat and then expose it to the air via a radiator (an oil cooler). Liquid cooling means using a water-based liquid (or non-water, if you use pure glycol), and a larger radiator out front. See air cooling vs liquid cooling here.

- Cam drive: The camshafts (which are the shafts with lobes on them that open and close the valves) on engines are driven by belts, chains, or gears. In most early Ducatis (since the 1980 Pantah) they were driven by belts, but in recent years, Ducati has been moving to gears.

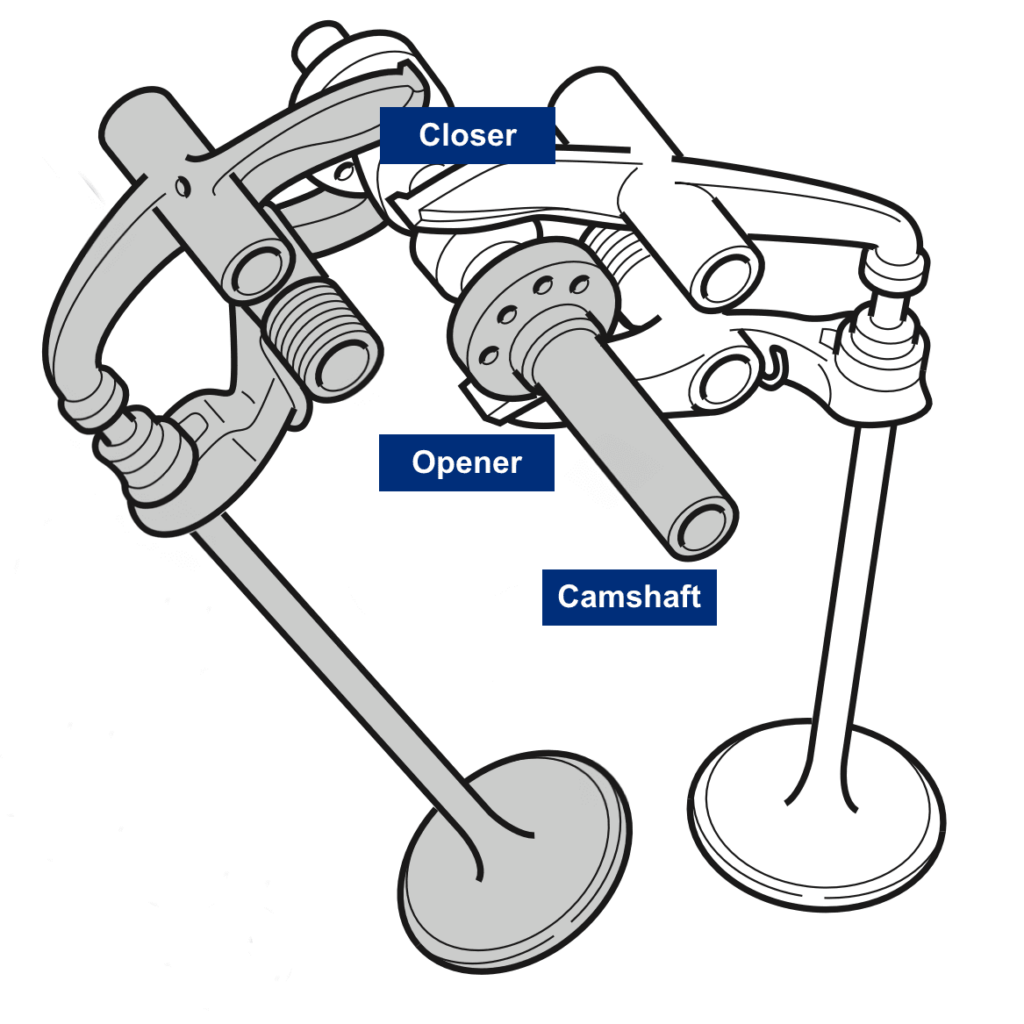

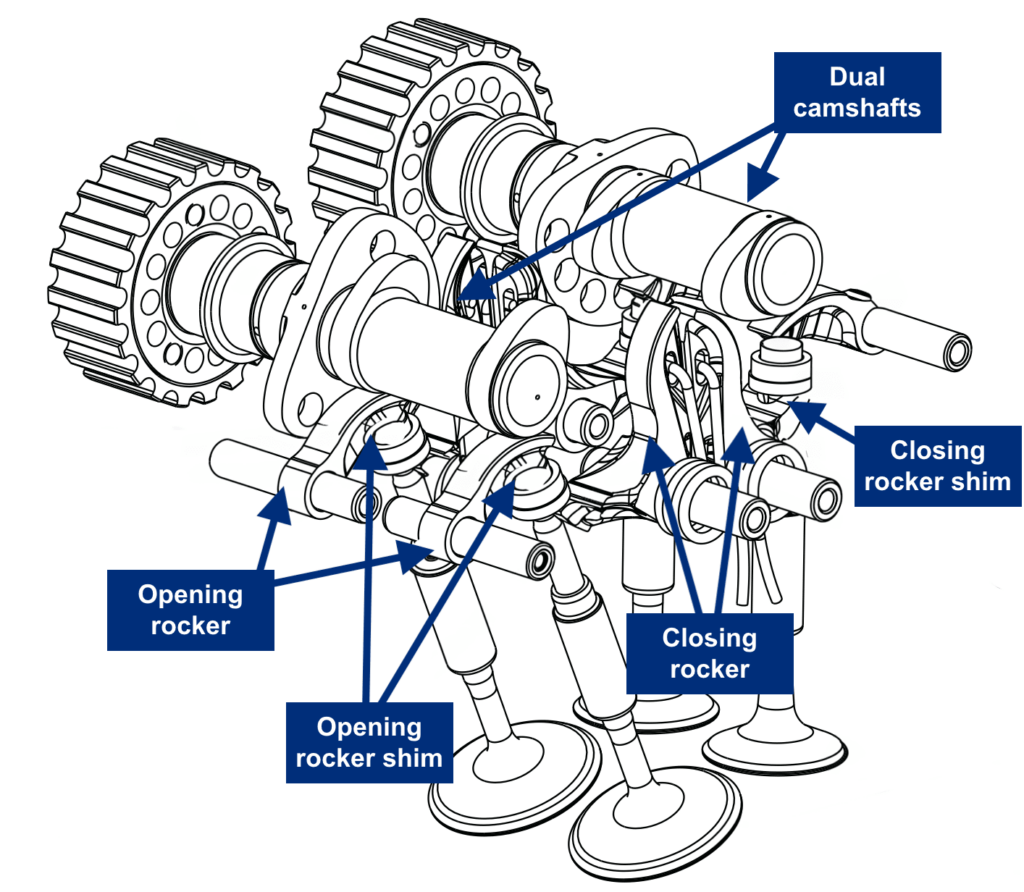

- Valve return: In most motorcycles, valves are opened by a camshaft lobe, and then closed by a spring. Ducati has used “Desmodromic” timing for ages, which means the valve is opened and closed by a camshaft lobe. There were various advantages to this which have diminished over time, but it’s still important to know as it affects the valve service job’s complexity. See more about desmodromic timing here.

- Valve overlap: The duration (expressed in degrees) of engine rotation where the inlet and exhaust valves are both open. High overlap makes for messy operation at low RPMs and thus a rough idle, but helps optimise flow for high-end power.

OK, with that terminology out of the way, let’s get into the Ducati engine types.

Desmodue

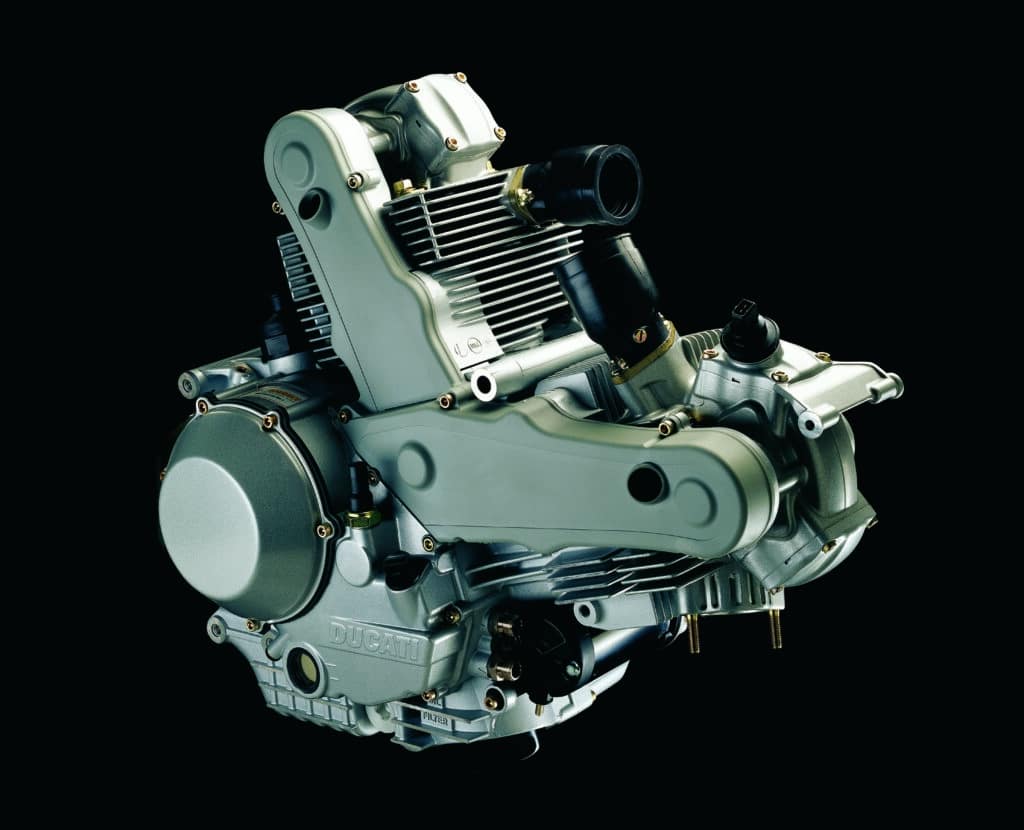

The “Desmodue” engine is a very long-running Ducati engine, being still in production and having been so for over fifty years.

Ducati used the “Desmodue” engine first in the 1971 Ducati 750 GT.

The Ducati 750 GT is considered Ducati’s most iconic motorcycle. It’s the nexus point of a technology that defined Ducati for the next 50 years. It’s sitting proudly in the Ducati Museum just outside Bologna!

Desmodue motors have two valves per cylinder and desmodromic timing. That’s where the name comes from — “desmo” (more on the meaning of this below). The overhead camshafts were driven by bevel gears. In 1980, with the first Ducati Pantah, Ducati moved to belt-driven camshafts for their Desmodue engines. Ducati kept this design for their Desmodue engines until today.

The majority of Desmodue motors are air-cooled or air/oil-cooled, but some of them are liquid cooled (like on the Ducati ST2, one of the ST series of motorcycles).

Desmodromic timing means that the valves are opened by camshafts as well as closed by them. In most motorcycles (and some Ducati recent ones), valves are closed by return springs. In the past, Ducati deemed these springs not fast enough for high-performance use, and so use camshafts to actively close the valves.

See here for more about Ducati desmodromic timing systems.

There were many, many Ducati motorcycles with the Desmodue engine. These have included

- All Ducati Monsters from the M900 to the Monster 1100 Evo (right before the 1200), which also includes the “smaller” Monsters, from the 600 (and limited-market 400) to the 796, including carburettor and EFI models

- The early Hypermotards (1100, 796)

- The early Supersports, both carburettor and EFI models

- The Sportclassic series, which had the 1000 engine (all fuel-injected)

- The early-gen Multistrada 1000 and 1100 (all fuel-injected)

Here are some common capacities / engine specs for the Ducati Desmodue motorcycles.

| Capacity | 696 | 803 | 904 | 992 | 1078 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bore / Stroke | 88 x 57.2 mm | 88 x 66 mm | 92 x 68 mm | 94 x 71.5 | 98 x 71.5 mm |

| Fuelling | Carb / EFI | Carb / EFI | Carb / EFI | EFI | EFI |

| Common Models | Monster 695, 696 | Monster (inc. S2R), Supersport, Scrambler | Monster, Supersport | Multistrada 1000, Monster 1000 (inc. S2R), Supersport, Sportclassic, ST2 (liquid-cooled) | Multistrada, Monster, Scrambler |

In the early days, Ducati Desmodue motorcycles had 6000 mile / 10000 km valve service intervals, but Ducati extended this to 7500 mile / 12000 km in the mid-2000s. Similarly, Ducati used to require cam belt replacements every two years; they extended this to five.

Ducati still uses the Desmodue architecture in the modern classic Ducati Scrambler 1100 and Ducati Scrambler 800.

The main downfall of the Desmodue engines is that the service intervals are pretty narrow. Every oil change, you also need to check and adjust the valve clearances. For decades Ducati has used shim-under-bucket valves, which means having shims on hand and doing math… it’s a job that takes a few hours at least, including an oil, filter, and belt change.

The second negative is that because of the two-valve design, they’re not great at making high-end power. But they’re still good for motorcycles designed for mid-range punch, like the Ducati Scrambler line.

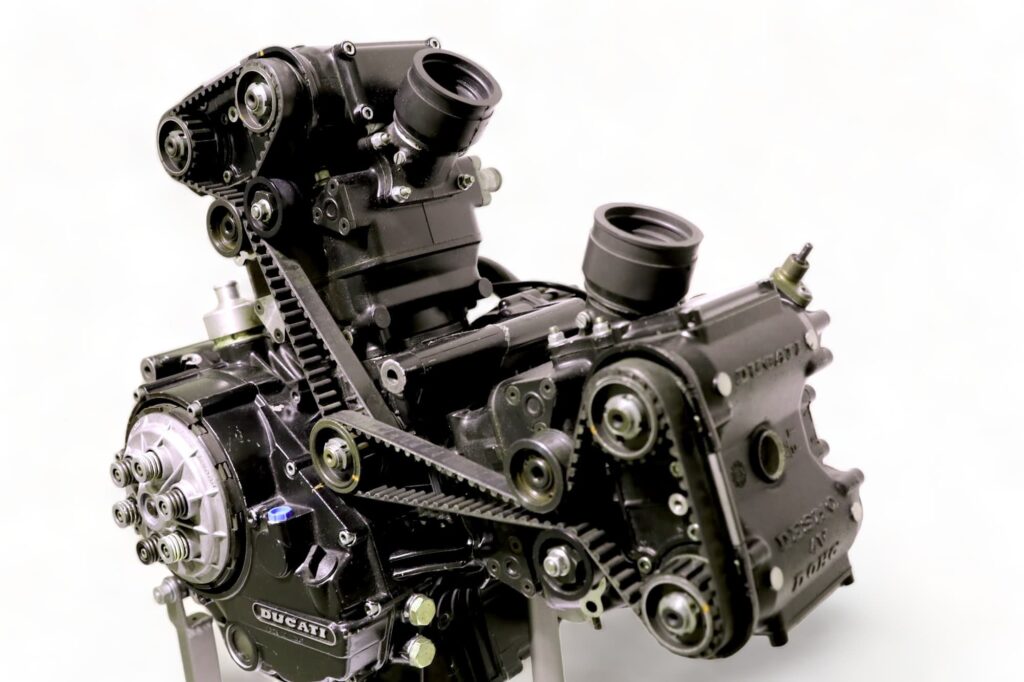

Desmoquattro

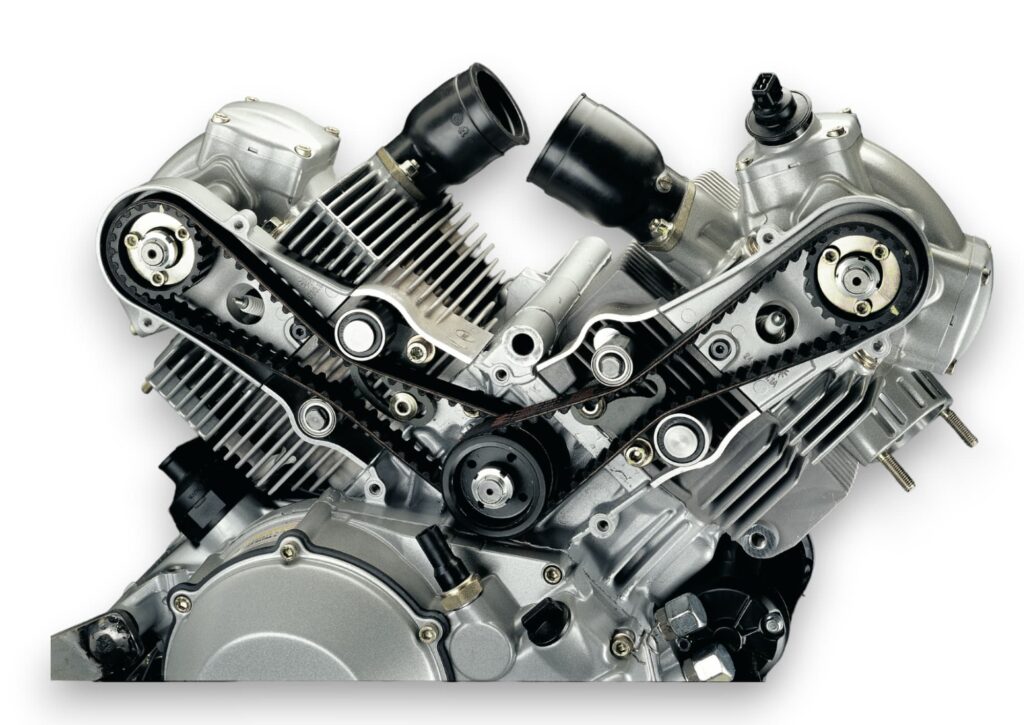

“Desmoquattro” is Ducati’s name for an engine with desmodromic timing and four valves per cylinder. “Desmo” means “desmo” (you’re welcome), and in Italian, “quattro” means “four”. They’re also all liquid-cooled and use belt-driven camshafts. This is one of the most iconic Ducati engine types.

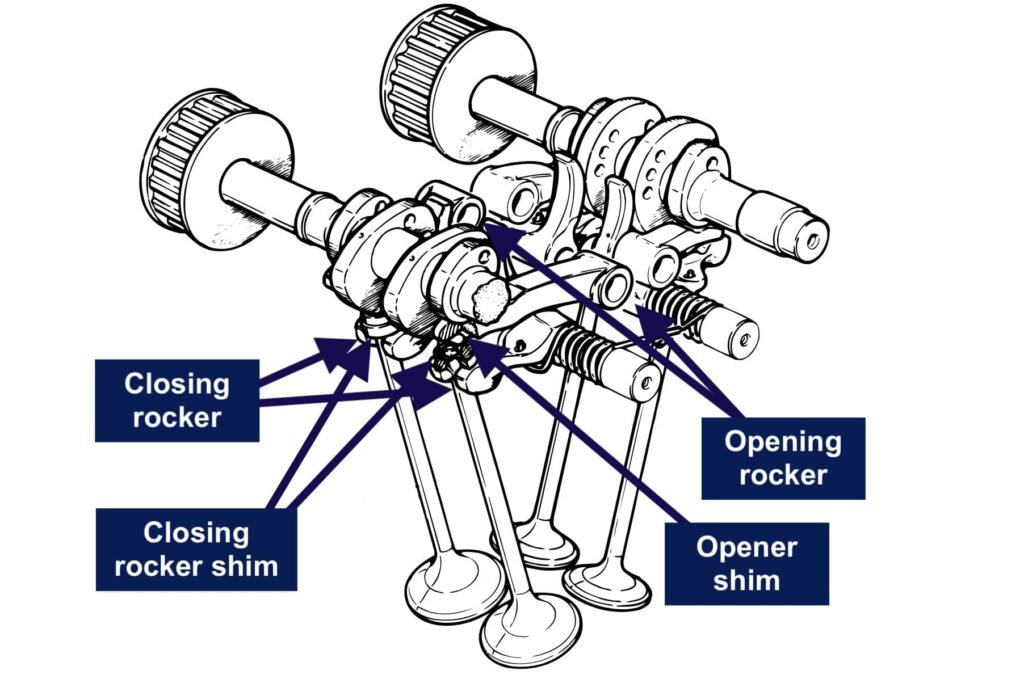

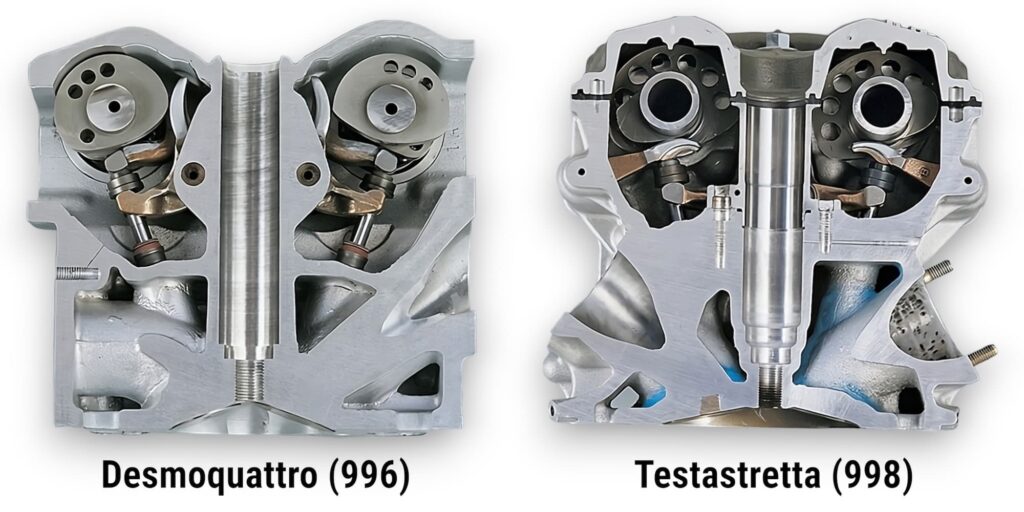

In a Desmoquattro motor, there are two overhead cams. There are eight rocker arms (4 openers and 4 closers). Each of those rockers has a shim, and thus there are sixteen clearances to check.

Ducati came up with the Desmoquattro design shortly after the Castiglioni brothers from Cagiva bought Ducati in May 1985. They needed to make a higher-power engine, ideally one that could be used in existing chassis. So the prescription was four valves per cylinder, plus aggressive camshaft timing of 40 degrees of valve overlap, optimising for top-end power (and a rough idle).

Ducati first used the Desmoquattro design in an endurance racer, the Ducati 748 i.e. (no relation to the later younger sibling of the 916), but the first production bike with a Desmoquattro design was the 851 Superbike.

Ducati used the Desmoquattro engine for just over two decades in its superbikes, as well as in a few other motorcycles like the Monster S4 series. It includes the Testastretta line of engines as well, but they’re worth separating out because of some unique features.

These days, motorcycles with early Desmoquattro engines are collector’s items. Even base-model versions of the 916 and 996 are pricey, and let’s not even talk about the up-spec race bikes!

Desmotre

For the sake of completion, there was the brief (but very decent) Ducati Desmotre engine. This had the base of a 992 cc Desmodue, but with a three-valve-per-cylinder head (two inlet valves, one exhaust), and also liquid cooling. It was released in only one motorcycle — the Ducati ST3 / ST3s.

The Ducati ST3 makes nearly as much power as the superbike-derived ST4 in other members of the ST range – with more torque, to boot. It just doesn’t rev quite as high (which is what having less breathing capacity will do), so it can’t make that top-end power.

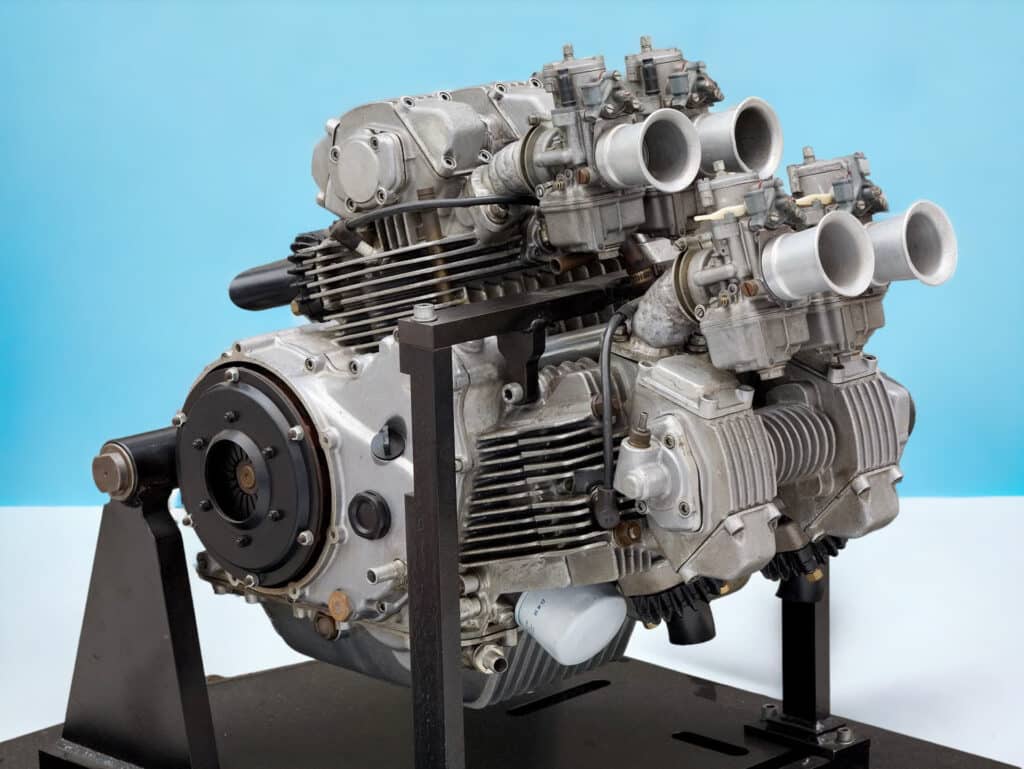

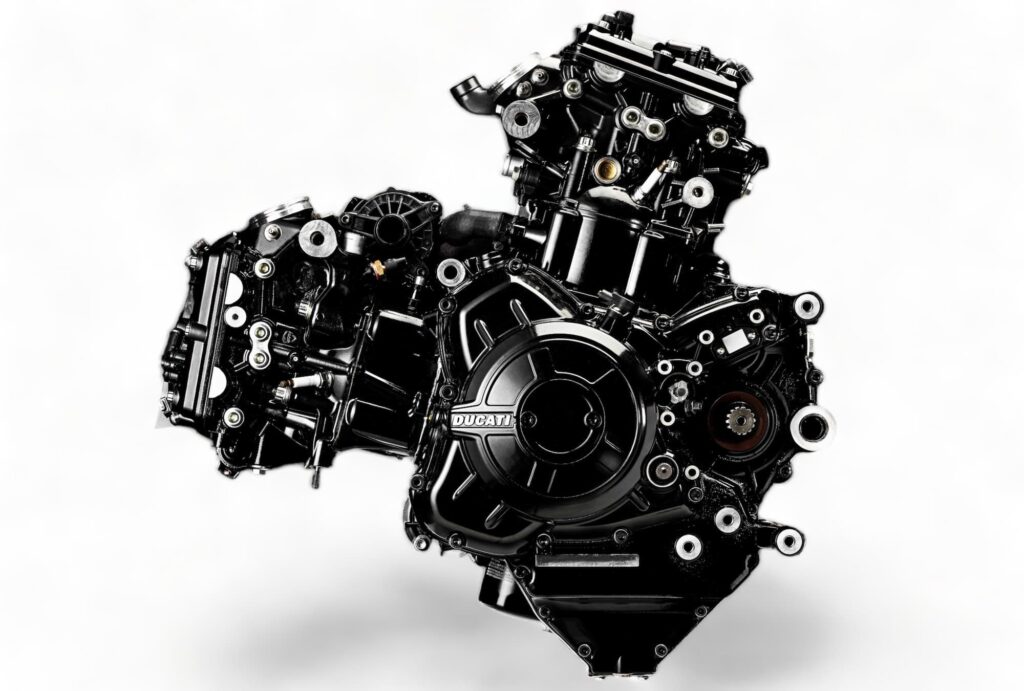

Desmosedici D16RR (for the Desmosedici RR)

You’d be forgiven for not having seen this Ducati engine in a motorcycle in person. But you should know it exists!

The Ducati Desmosedici is a Ducati V4 engine — one of the early ones (though not the earliest). Ducati uses V4 engines in racing, and has made many Desmosedici GP motorcycles, but they never released them for the public until the Desmosedici RR. In Italian, “sedici” means “sixteen”, which is how this motorcycle gets its name: named for the number of valves in the motorcycle (four per cylinder).

Ducati released a very limited run of 1,500 Desmosedici RR models as homologation superbikes for the lucky public. They’re one of the rare Ducati motorcycles that’s more expensive than when they were originally sold. Presuming they’re treated well, they hold their value or even appreciate.

The V4 engine in the Desmosedici RR is a 989 cc four-cylinder engine in “L” layout (again, like V, but forward leaning). It has four valves per cylinder, and double overhead cams that are gear driven.

Ducati said that the gear-driven cams are a “sophisticated and reliable solution that enables precise valve timing in all conditions”. Sounds great as a marketing pitch, but this performance had no encore — Ducati started moving to chain-driven cams later, instead.

The Desmosedici RR was, according to Ducati, the first bona fide MotoGP motorcycle that you could buy in street trim. There are definitely very few of these motorcycles in general. The D16RR engine has pistons with the same bore and stroke as on the GP bike, as well as the same desmodromic timing parts, valve angle, distance between cylinder centres, and ignition timing.

But of course, the D16RR is homologated for street use and Euro 3 emissions (the standard at the time). Still, the rated power output is a hefty 200 hp / 147 kW at 13,800 rpm.

In reality, while the Desmosedici RR’s engine has the same format / layout as that of the race bike, it doesn’t share many components. The only components shared are the cylinder head base bolts. The rest of the D16RR was designed for production.

As a curious note in the history of Ducati V4 engines, Ducati chief engineer Fabio Taglioni did experiment with an air-cooled V4 in the 80s, the “BiPantah”, as it was basically two Pantah engines together. But they opted for a liquid-cooled L-twin, the Desmoquattro, instead.

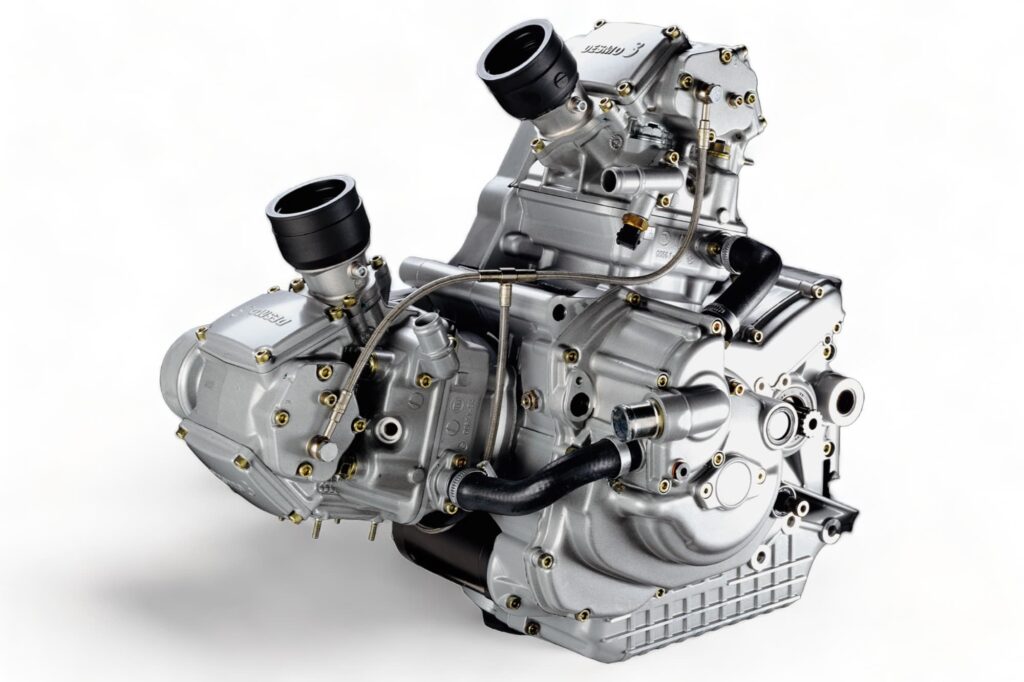

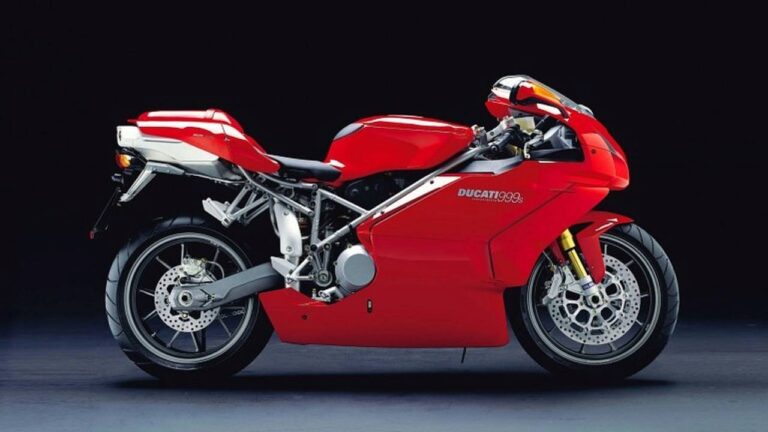

Testastretta Engines

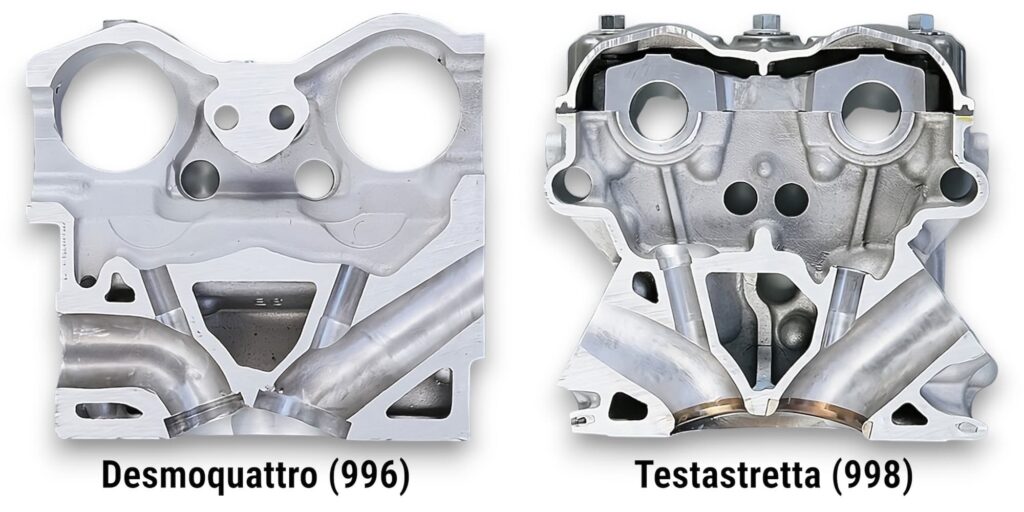

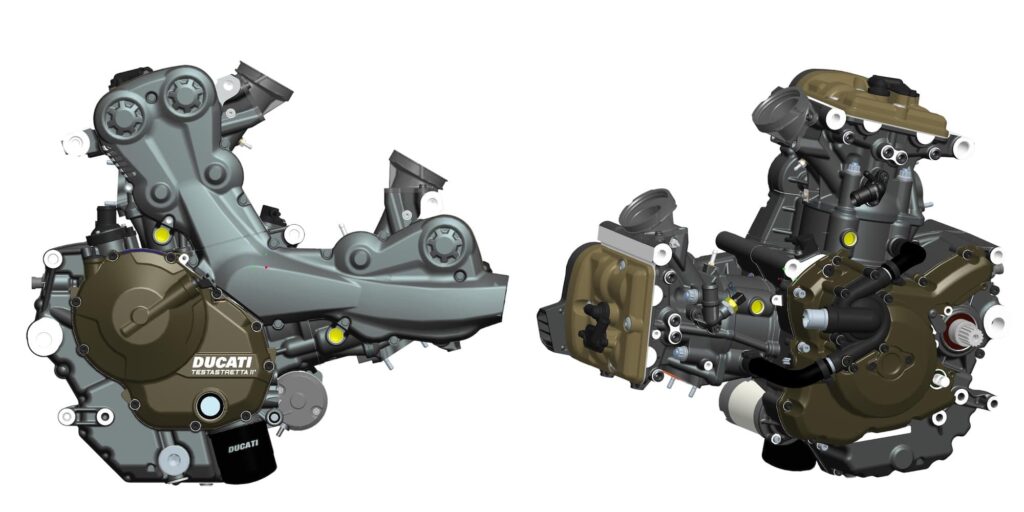

The “Testastretta” is technically a subclass of the Desmoquattro Ducati engine type, because it also has the same characteristics — four valves per cylinder, desmodromic timing, and belt-driven camshafts.

First, where the name “Testastretta” comes from, because that helps understand the engine nomenclature. The words “testa” and “stretta” together mean “narrow head” in Italian. You might also know of the Ferrari “Testarossa”; “testa rossa” means “red head”. Or someone who’s “testy” is “headstrong”, which is where the word comes from.

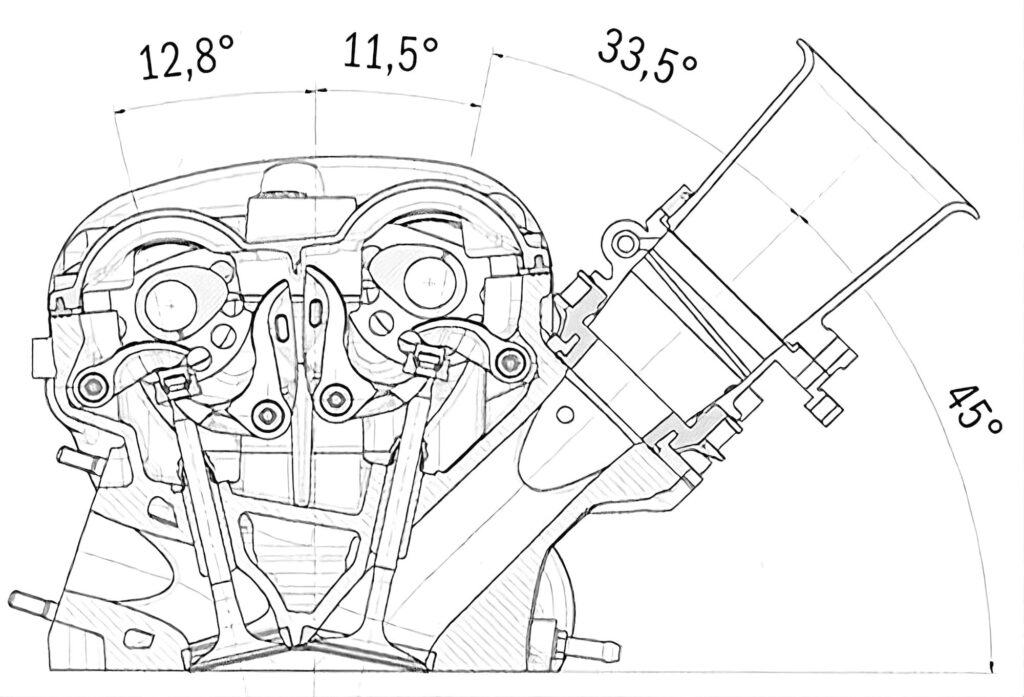

The genesis of the Testastretta was, as usual, a quest for more power for the Ducati 996R race bike. The story is quite interesting — below is a summary of an interview with Inginiere Filippo Preziosi, technical director of Ducati Corse in the early 2000s (see here for the interview, with a somewhat weird translation from Italian.)

Ducati wanted to increase the bore (from 98 to 100 mm) and correspondingly shorten the stroke (from 66 to 63.5 mm) to meet displacement constraints — a common general trend towards “oversquare” superbike engine design, making for higher-revving, peakier, and higher-power engines.

But to achieve a high compression ratio with that increasingly oversquare design, using the old valve angle of 40 degrees, means you’d need a very distorted piston shape. This leads to inefficient combustion.

So Ducati sought to reduce the valve angle from 40 degrees to 25 degrees for the 996R — and thus named the engine the “Testastretta”.

The narrower angle in the Testastretta engine gives a number of benefits, but it can be summarised as “improved airflow”. This comes about as a result of being able to fit the larger valves and to use a flatter, more compact and efficient combustion chamber. The more complete combustion means that the engine could run a higher compression ratio and make more peak power. See this discussion by Kevin Ash for more info.

But it wasn’t as simple as “Yo, let’s fit some bigger valves”. The designers at Ducati had to do some engineering jiu-jitsu to make them fit. Ducati moved the rocker pivots to the outside of the cams to make the space. The rockers, openers, and closers are all lighter, too, which means less reciprocating mass. Finally, the design has the side benefit of making valve services simpler, by the way, as access is easier.

Compare this diagram with the one above from the Desmoquattro and you’ll see some of the differences.

Ducati continued using the Testastretta engine design from the 996R through to the 998 and 999. Ducati used the original Testastretta engine in

- The Ducati 996R, 998, and 999

- The Ducati 749, the little sibling to the 999

- The Ducati Monster S4R (Testastretta) and S4Rs

Here are the dimensions of the various Testastretta (pre-Evoluzione) motors.

| Model | 996R / 998 / 999 Monster S4R | 998R / 999R | 749 | 749R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity (cc) | 998 | 999 | 748 | 749 |

| Bore (mm) | 100 | 104 | 90 | 94 |

| Stroke (mm) | 63.5 | 58.8 | 58.8 | 54 |

Yes, you read that right. The 999 didn’t have a 999 cc engine! But the 998R and 999R both did! C’mon, Ducati. Make it easy for us sometimes.

The Ducati 749R is a very rare bird, with a unique engine and high-spec components. Ducati didn’t make “R”-spec versions of its smaller motorcycles again.

Testastretta Evoluzione

From the Ducati 1098 Superbike, Ducati used the “Testastretta Evoluzione” engine name. “Evoluzione” is Italian for “This one is a bit better.”

Like the Testastretta, the Evoluzione motor is a liquid-cooled four valve per cylinder L-twin that’s really a sub-category of the Desmoquattro engine type.

Externally, you can recognise a Testastretta Evoluzione engine by the more compact cylinders and cylinder heads.

Ducati reduced the angle between the valves slightly from 25 degrees to 24.3, but also increased the size of the valves to 42mm inlet and 34mm exhaust.

To feed the revised cylinder heads, Ducati implemented elliptical throttle bodies, which feed 30% more airflow while maintaining the narrow design.

One particularly striking feature of the Evoluzione engine is the weight savings through revised manufacturing technology. Ducati saved a total of 5 kg (11.1 lb) by reducing the weight of many components, including the cylinder heads (with valve covers made of magnesium), transmission gears, gear selector drum, oil pump, and primary gears.

The Testastretta Evoluzione is on motorcycles including:

- The Ducati 1098 and 1198 Superbikes

- The Ducati 848 Superbike (including the Evo models and the original, which didn’t have “Evo” in its name)

| Models | 1098 | 1098R / 1198 | 848 (Superbike) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displacement | 1099 | 1198.4 | 849.4 |

| Bore | 104 | 106 | 94 |

| Stroke | 64.7 | 67.9 | 61.2 |

I want to make a special note on the 848 Superbike’s Testastretta Evoluzione engine.

It’s interesting to note that the 848’s motor is not just a sleeved-down / shorter-stroke version of the motor in the 1098, which was the case in the 748 for example. It’s actually built from the ground up, with many unique parts.

In fact, Ducati pioneered a new method of casting on the 848 — vacuum die casting — and then later brought it to the 1198. Vacuum casting is a method of casting that allows for greater precision. Without going into specifics (it’s a bit beyond my ken and I don’t want to just copy-paste a marketing spiel), it let Ducati use advanced design and check techniques to meet the required reliability standards while saving weight of 3.5kg over traditional methods.

Ducati also used a wet clutch on the 848. They had used wet clutches before, but this was the first time on a Superbike of any size — the 749, the previous “small” Superbike, had a dry clutch.

Note that the Streetfighter 848 did not get the Testastretta Evoluzione motor, but rather the Testastretta 11-degree head (though it has the same dimension bore / stroke).

Testastretta 11-degree

The Testastretta 11-degree is the name Ducati gave first to the engine in the first-series Ducati Multistrada 1200, but it’s still around today in motorcycles with the Ducati 937 motor, including… actually, five motorcycles (see the slider below).

The Ducati motorcycles with Testastretta 11-degree engines are still liquid-cooled, four-valve-per-cylinder motors with desmodromic valve actuation and belt-driven cams. So they share design foundation with the Desmoquattro.

In these motorcycles, “11-degree” refers to the amount of valve overlap (not valve angle, which is what characterised the Testastretta generation). This means that there’s 11 degrees of rotation in which the intake and exhaust valves are partially open.

“Overlap?? That sounds crazy,” you might think, as I did (and somewhat do). “The air/fuel mixture will come in through the intake and will just whoosh out the exhaust.”

That’s true in some ways, but it’s a small amount of overlap, and momentum is key, as the air/fuel mixture coming in actually helps to flush out the remaining exhaust gas.

Most motorcycle engines have a degree of valve overlap. But the key is to pick an amount of overlap that is optimal for a specific rev range. A lot of overlap works at high RPMs, and is good for high-end performance, but results in a rough idle. The converse is also true.

Ducati’s experimentation resulted in 11 degrees of overlap being a good amount for their street motorcycles like the Multistrada and the other engines with this format of motor.

There have been multiple generations of the Testastretta 11-degree:

- The original 1200 — derived from the 1198 Superbike motor (not the 1199, a Superquadro, but which also has 1198 cc displacement), with reduced valve overlap (and power) and improved low-rpm performance.

- The 848 in the Streetfighter 848 (note that the 848 Superbike used the regular, higher-power Testastretta Evoluzione 849 cc engine)

- The 821, which powered the Hypermotard 821 / Hyperstrada 821 first, then the Ducati Monster 821

- The 937, first in the Ducati Hypermotard 939, and now in all of Ducati’s sporty middleweights.

All of these motorcycles have fundamentally the same architecture — they have belt-driven cams, four valves per cylinder, and an 11-degree valve overlap.

| Testastretta 11-degree engine | 1198 (“1200”) | 849 (“848”) | 821 (just “821”) | 937 (“939” / “950”) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2016 |

| Model(s) | Multistrada/ Monster 1200 | Streetfighter 848 | Hypermotard/ Hyperstrada/ Monster 821 | Hypermotard/ Hyperstrada 939, Multistrada 950, Supersport, Monster [937], DesertX |

| Capacity | 1198 cc | 849 cc | 821 cc | 937 cc |

| Bore / Stroke | 106 x 67.9 mm | 94 x 61.2 mm | 88 x 67.5 mm | 94 x 67.5 mm |

There are also the DVT motors used in the Multistrada and Diavel, both 1200 and 1260 (see below).

The 937 is the only one still in use, and it’s in quite a bit of use! Ducati is still releasing models using this motor.

Below is a slider of motorcycles with the 937 cc Testastretta 11-degree motor.

Testastretta DVT (1200 / 1260)

Ducati updated their larger Testastretta 11-degree motor with variable valve timing, which they call DVT — for “Desmodromic Variable Timing”. Ducati puts Desmodromic everywhere: in its motors, in its acronyms, in its sandwiches, etc.

Ducati first released a DVT motor in the Multistrada 1200, and then later in the XDiavel, then the Multistrada 1260 and the Diavel 1260, all after the Multistrada coming with the bigger 1262 cc DVT engine.

The Testastretta DVT shares the same main architecture features as the Testastretta 11-degree engine — belt-driven camshafts, dual overhead cams, and four valves per cylinder — but of course, it has the variable valve timing tech.

The DVT system allows Ducati to independently vary the timing of the intake and exhaust camshafts. This allows for a tune that’s smooth and responsive at low RPM but high-power at high RPM, while conforming to emissions laws.

“How’s that work?” you ask. Well, it took me a while to figure out, and don’t count on me to take one of these apart and put it back together again, but I think it goes like this.

The core of how DVT works is by altering valve overlap. At low RPM, the DVT system sets low overlap, and at high RPM, it sets high overlap.

The DVT mechanism works via valve timing adjusters built into the gear ends of the two overhead camshafts. Flick through the below slider for a brief explainer.

The engine’s ECU engages the DVT mechanism via oil pressure. It opens dedicated valves. When the valves are open, oil releases into chambers in the camshafts’ DVT mechanisms, and DVT engages.

While I’m not sure of the exact timing / overlap that the DVT engine provides, all the literature seems to point to conventional 11-degree overlap at low RPM / loads, with overlap closer to the superbikes at higher RPM / loads.

Even though the DVT system seems quite complicated, it doesn’t affect the complexity or frequency of the major valve service. The valve service intervals for the Testastretta DVT motor is still 18000 miles / 30000 km, and the job is the same — clearances are specified for when DVT isn’t engaged obviously (as the motorcycle is off and cold).

Nonetheless, Ducati is retiring the DVT motor in favour of the V4 Granturismo. Still, the door is open for variable valve timing in other commercial motorcycles in the future, maybe in the V4 engines.

Superquadro (2012+)

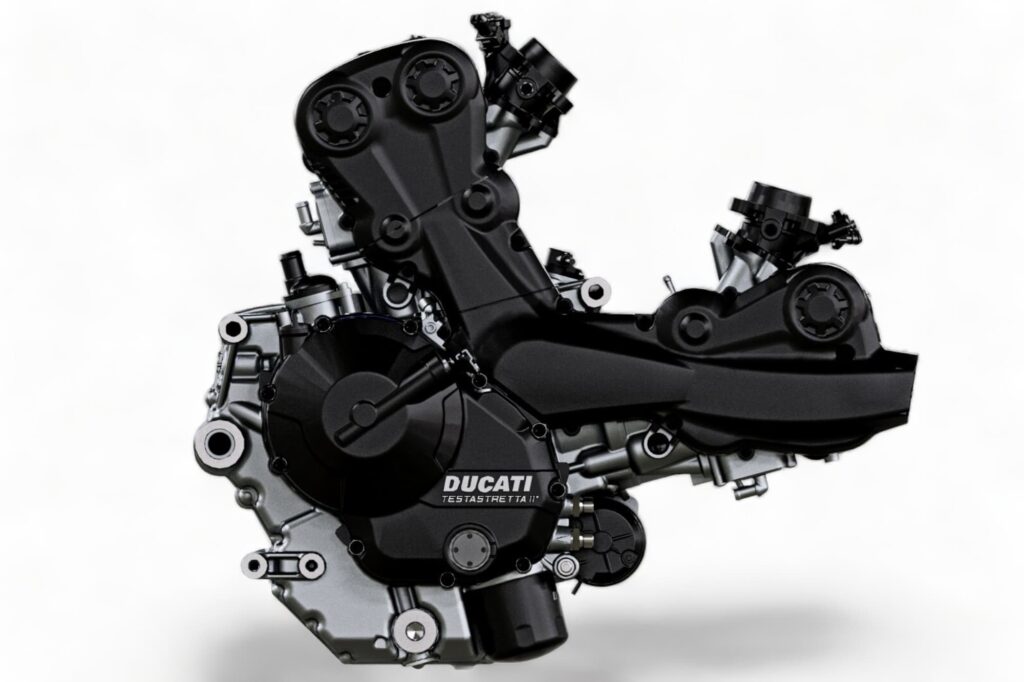

The Ducati Superquadro was first released with the Ducati Panigale 1199. It’s a huge change from the engine that preceded it, the Testastretta Evoluzione.

Ducati insisted that they gave their engineers a “blank canvas” of requiring 25 more horsepower and 10kg less weight (in the motorcycle), and let them have a free run to achieve that however they wanted.

The word “superquadro” is actually a commonly used term in Italian — it means “oversquare”. Ducati just borrowed the word and made it into a brand, just like they did with the “Ducati Scrambler”.

“Oversquare” means the bore is wider than the stroke is long; in other words, pistons are short and wide rather than tall and thin.

Most motorcycle engines are oversquare, and most superbike engines are very oversquare. Oversquare engines tend to have lighter pistons and shorter crankshafts, and thus are more inclined to rev higher. So, the motors are more inclined to produce high-rpm power than low-rpm torque. (See here for more discussion on the relationship between bore, stroke, and engine displacement.)

But Ducati named this motor the “Superquadro” because it’s considerably more oversquare than the previous gen. From the 1198 Superbike to the 1199 Panigale, the bore:stroke ratio increased from 1.56:1 to 1.84:1.

The main things the Superquadro has in common with the Testastretta Evo is that it, too, is a liquid-cooled L-twin with four valves per cylinder and desmodromic timing. But here’s what changed:

| Item | 1198 Superbike | 1199 Panigale | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bore / Stroke | 106 x 67.9 mm | 112 x 60.8 mm | Increase of bore/stroke ratio from 1.56 to 1.84:1 (much more oversquare) |

| Displacement | 1198.4 | 1198.0 | Effectively the same |

| RPM ceiling | 10,700 | 11,300 | Helped by shorter stroke |

| Peak power | 125 kW / 170 hp @ 9750 rpm | 143 kW / 195 hp @ 10,750 rpm | 25 hp increase! |

| Valve material | Steel | Titanium | Previously Titanium was just on R-spec bikes |

| Camshaft drive | Toothed belts | Chain | No more belts to replace every five years / valve service |

| Valve service interval | 7500 mi / 12000 km | 15000 mi / 24000 km | Double the service interval; much lower major maintenance cost |

The change in service interval is noteworthy. The valve service on a Ducati desmo engine is a notorious milestone. It’s no surprise that the vast majority of Ducati motorcycles available for sale as private sales make no mention of when the valve service was done. Often, they’re due around the time of sale.

So to see valve service intervals extended to a much more reasonable (and quite median, among other manufacturers) 15000 miles / 24000 km is very welcome!

The change to chain-driven camshafts is also a big move. For many years, Ducati was known for using toothed belts for being lighter. Changing belts in a Desmo motor was just one of those things owners were to be aware of. Having one fewer thing to worry about always helps.

Ducati still uses belt-driven cams on its Desmodue and Testastretta-series motors, which are still in production in some motorcycles.

After the 1199 Panigale, Ducati kept the Superquadro design in the 1299 Panigale, as well as in the little siblings to both, the 899 Panigale and 959 Panigale.

Here are the various engine sizes / dimensions of the Superquadro:

| Engine “name” | 1199 | 1299 | 899 | 959 / V2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First model year | 2012 | 2015 | 2014 | 2016 |

| First model | 1199 Panigale | 1299 Panigale | 899 Panigale | 959 Panigale |

| Capacity | 1198 cc | 1285 cc | 898 cc | 955 cc |

| Bore / Stroke | 112 x 60.8 mm | 116 x 60.8 mm | 100 x 57.2 mm | 100 x 60.8 |

| Bore:Stroke ratio | 1.84:1 | 1.91:1 | 1.75:1 | 1.64:1 |

Ducati still uses the Superquadro design today in the Panigale V2 (which is being sunsetted as of 2025), the update to the Panigale 959 and still the little sibling to the Ducati Panigale V4, as well as in the Ducati Streetfighter V2.

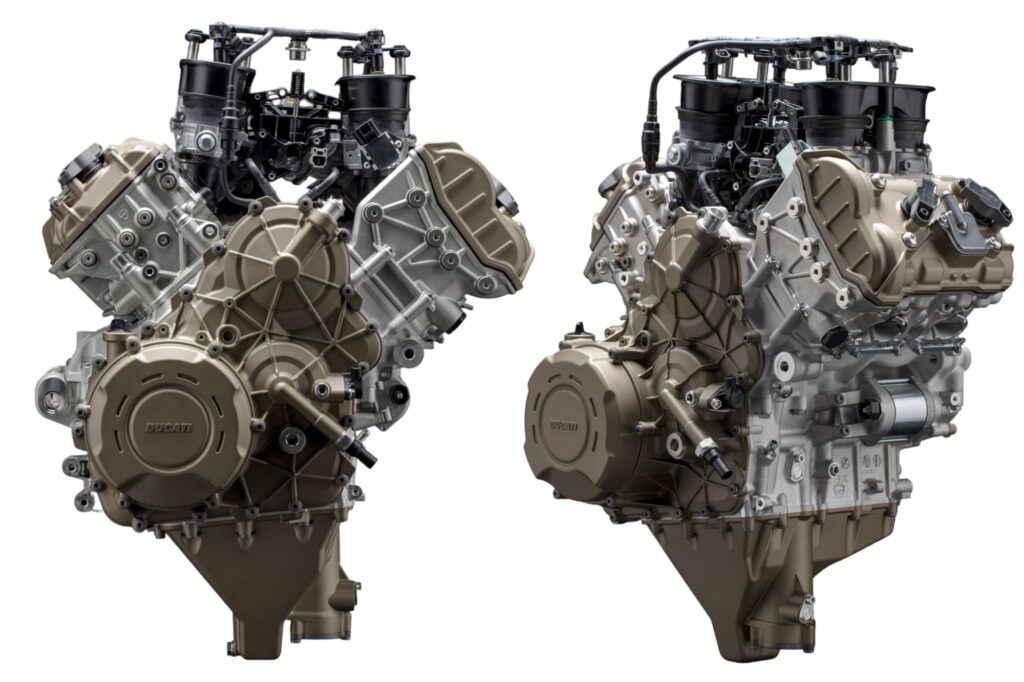

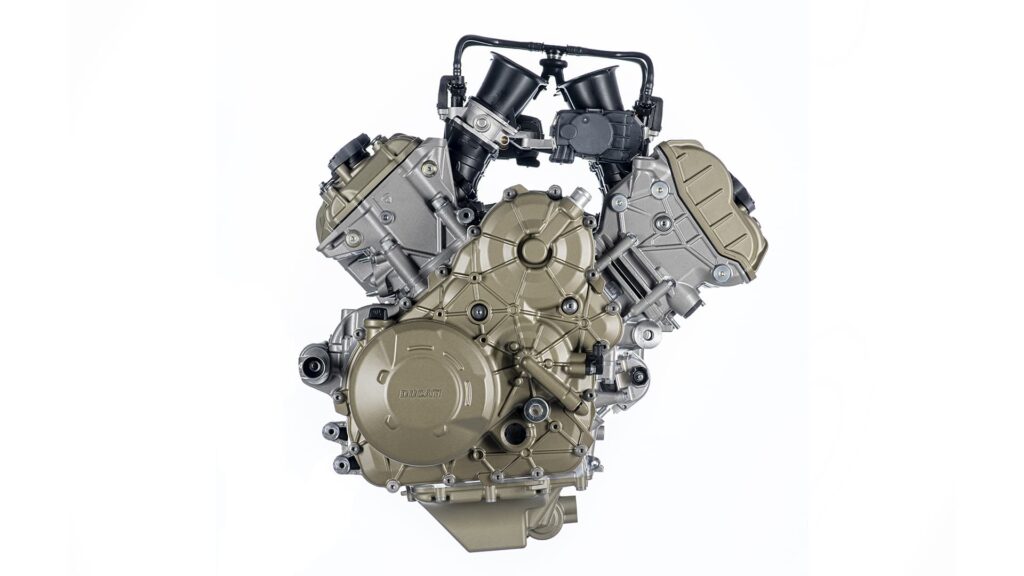

Desmosedici Stradale (the V4) (2018+)

Finally, we get to the Desmosedici Stradale! It seems like it has taken forever to get to one of Ducati’s most well-known engines of today.

For the longest time, Ducati was known for making V-twins (ok, fine, “L-twins”). So it was to quite a bit fanfare that Ducati announced the Panigale V4 at the Italian EICMA show in 2017, where it won Motociclismo’s “Most Beautiful Bike” popular vote.

The Desmosedici Stradale is named after the GP motor in the Desmosedici RR (see above). “Stradale” means “road-oriented” or “adapted for the road” in Italian. You might know the word “Strada” from “Multistrada”, which means “many roads”. Or from any trip to Italy, driving along the autostrada at high speed.

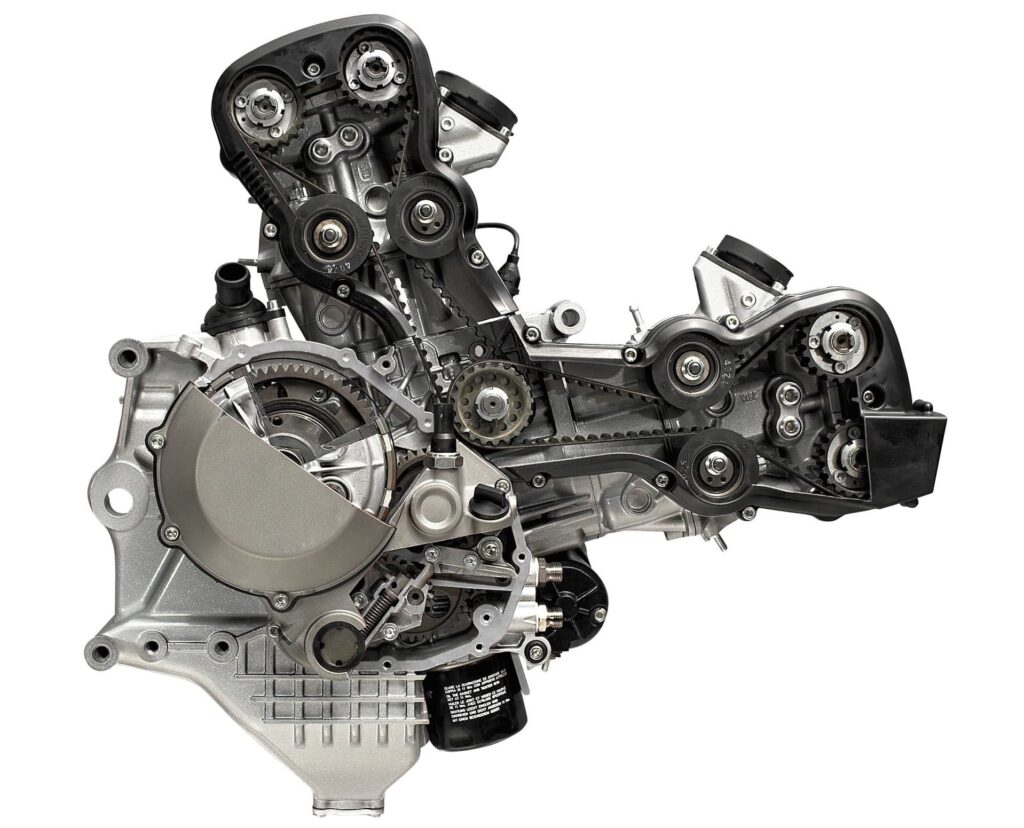

The Desmosedici Stradale Ducati engine keeps a few hallmarks of its Superquadro predecessor. It has chain-driven camshafts, desmodromic timing on the valves, and the motor is still a liquid-cooled L-shaped motor — though of course there are four cylinders now, rather than two.

The engine keeps the 81 mm bore from the MotoGP V4 motorcycle, but gives it a longer stroke, raising total displacement to 1103 cc. The longer stroke and larger displacement let Ducati tune the Desmosedici Stradale for more low-end torque and good high-end power, without having to tune it too aggressively — you can still run the Panigale V4 on regular 95 RON (91 PON) “Premium”, which is the standard fuel in Europe (known as “Super” unleaded).

In the Desmosedici Stradale, each part of the “V” is now a bank of two cylinders. Each has four valves, and both openers and closers. Which means… four cylinders times four valves times opener + closer — 32 clearances to check. Luckily, the valve service interval from the previous gen is maintained at 15000 miles / 24000 km.

Like on Ducati’s L-twins, the cylinders fire 90 degrees apart. But Ducati also uses a 70-degree crankpin offset. The result of this is a firing order (in a 720-degree four-stroke cycle) of 0, 90, 290, and 380.

In other words

- 0o: Front cylinder on alternator side fires

- 90o later: Rear cylinder on same side fires

- 200o later: front cylinder on other side fires. (180o would be a half-rotation.)

- 90o later: Rear cylinder on same side fires

- 340o (nearly a whole revolution) later: Back to square 1.

Ducati cited two reasons for choosing a V4 over continuing to iterate on the V-twin or choosing an inline 4, like most other superbike manufacturers.

Firstly, the 90-degree V layout eliminates the need for a balancing countershaft to eliminate vibration. The use of countershafts is always a compromise. They reduce vibes, but they also increase reciprocating mass, reducing responsiveness and peak power. So the layout lets Ducati build a vibe free engine that revs to over 15000 rpm in some configurations.

Secondly, the V4 is more laterally compact than an inline-four, which means the motorcycle can be narrower. The shorter crankshaft also diminished the gyroscopic effect, which improves handling.

The V4, with its smaller cylinders, also revs quite a bit higher than the V-twins ever did. The higher-spec V4R revs especially high..

You might think that a V4 would be a lot larger and heavier than a V-twin. While this would normally be so, Ducati was able to rely on a lot of tech from their racing division (which has been using V4s for ages), and the end result is that the Desmosedici Stradale is just 2.2 kg heavier than the 1285 cc Superquadro twin.

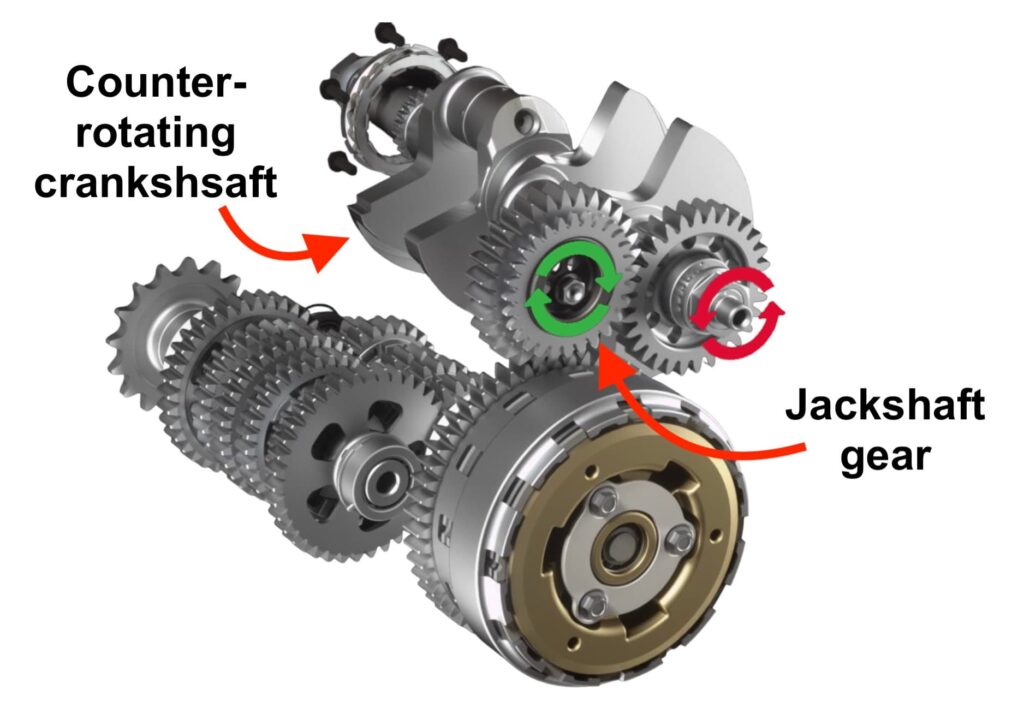

There’s one more special bit of technology that Ducati has used in the Desmosedici Stradale: a counter-rotating crankshaft. The crankshaft rotates in the direction opposite to the rest of the drivetrain, which quells gyroscopic effect, and helps the motorcycle tip more easily. It also counters a motorcycle’s tendency to wheelie or for the rear wheel to lift up under heavy deceleration.

This is very high-end, race-spec technology, used in MotoGP bikes but few other street motorcycles (with the Moto Guzzi V100 Mandello being an interesting example, but used there to quell longitudinal roll, as the engine in that motorcycle is mounted longitudinally).

Of course, even Ducati admits that the counter-rotating crankshaft necessitates an extra transmission element to reverse the rotation direction before transmitting it to the wheels. Ducati calls this the “jackshaft”, and says it’s responsible for a generally accepted additional 2% power loss between the crankshaft and the rear wheel.

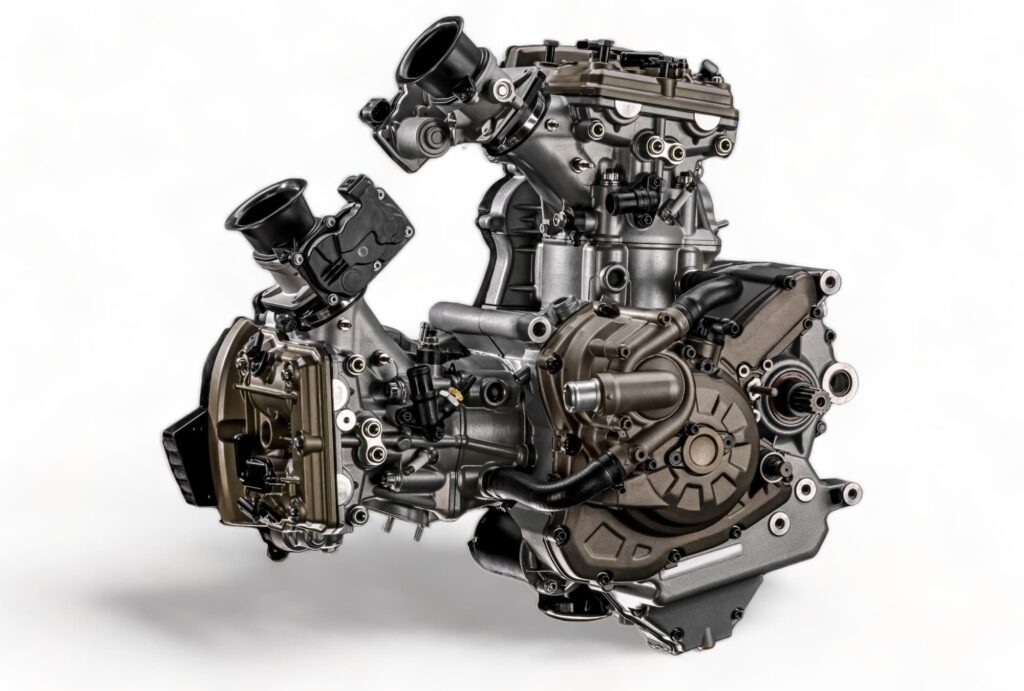

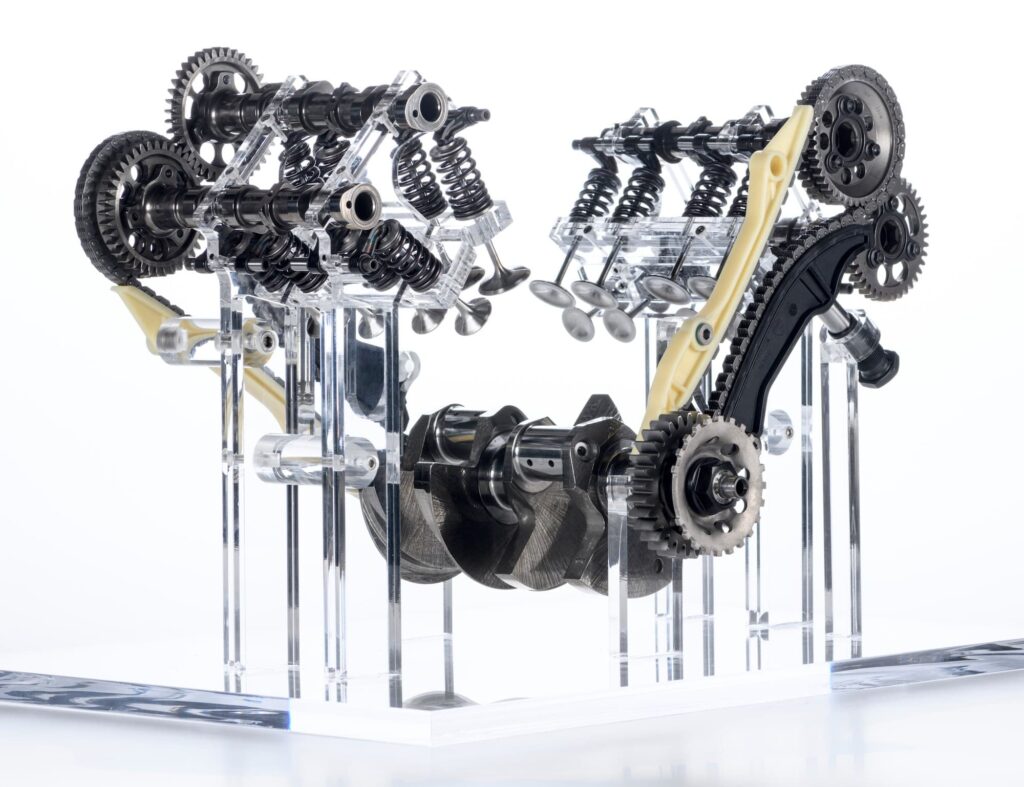

The timing control system of the Desmosedici Stradale is quite interesting. The camshafts are controlled by two timing chains (one for each leg of the “V”). But the chains only drive one camshaft; the other is driven by a gear.

It gets more interesting. At the front, the chain drives the intake camshaft, which drives the exhaust camshaft via a pair of cogs. At the rear, the chain drives the exhaust cam, which drives the intake via cogs. The exploded diagram in the section below for the V4 Granturismo makes this clear.

Here are the currently specs of Ducati Desmosedici Stradale engine formats.

| Capacity | Base spec | R-spec (smaller capacity, higher power) |

|---|---|---|

| Motorcycles | Panigale / Streetfighter V4, V4S | Panigale V4R |

| Displacement | 1103 cc | 998 cc |

| Bore / Stroke | 81 x 53.5 mm | 81 x 48.4 mm |

| Maximum engine speed | 14500 rpm / 15000 rpm (6th gear) | 16000 rpm / 16500 rpm (6th gear) |

Aside from the Panigale V4, the Desmosedici Stradale also is in the Streetfighter V4, as well as in the 2024 Multistrada V4 RS. Some of the base trims (the SP models) have a dry clutch, as does the Multi V4 RS.

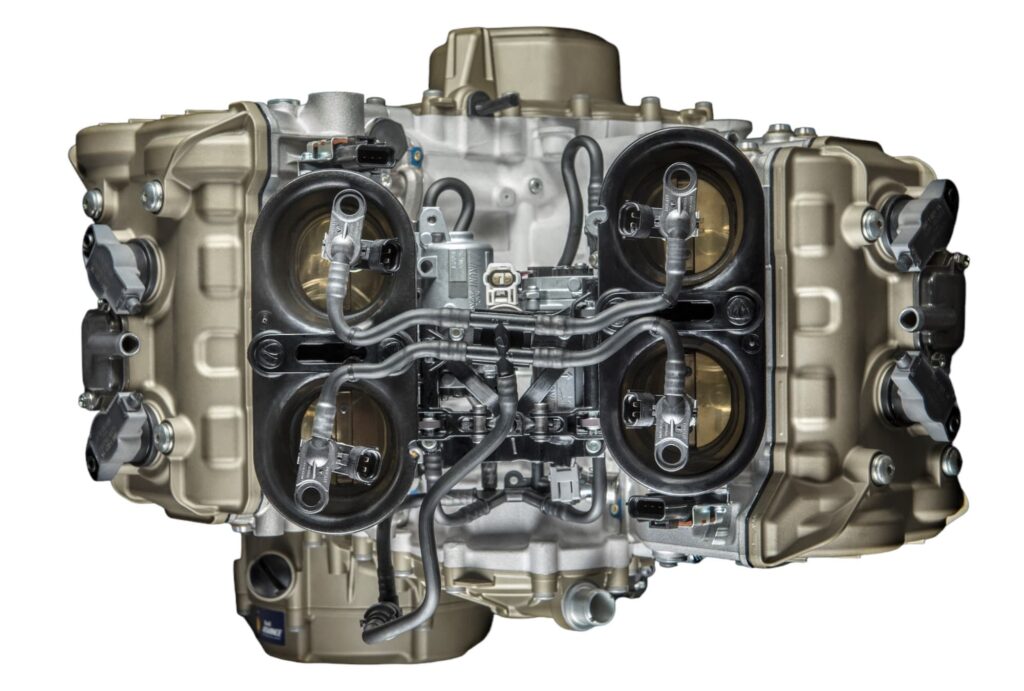

V4 Granturismo (2021+)

Ducati announced the V4 Granturismo along with the Multistrada V4, in which it pioneered, for the 2021 model year. Ducati has now also released it in the Ducati Diavel V4, and I suspect it’ll make it to at least one or two other high-end machines.

The V4 Granturismo is Ducati’s second major commercially available V4 engine, after the Desmosedici Stradale.

There’s quite a lot that’s different about the V4 Granturismo when comparing it with the Desmosedici Stradale. But let’s look at first what’s similar between the two engines:

- The design concept: Both engines are liquid-cooled 90-degree V4 engines with dual overhead cams and four valves per cylinder.

- Counter-rotating crankshaft: They both have it, and benefit from it in the same way.

- Twin pulse: Both motors have a 70-degree offset and the same firing order / pattern.

- Timing system: Both motorcycles use a combination of chan and gear-driven camshafts, with the chain driving one cam, and the second in each “V” being driven by cogs.

- Same stroke of 53.5 mm, same aggressive 14.0:1 compression ratio

Aside from those aspects, here are the things that are different between the two Ducati motorcycle engines.

| Item | Desmosedici Stradale (Panigale V4 base) | V4 Granturismo (Multi V4) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| First year | 2018 | 2021 | |

| Rear bank deactivation | No | Yes | For comfort & efficiency on the Multi / Diavel |

| Capacity | 1103 cc | 1158 cc | |

| Bore / Stroke | 81 x 53.5 mm | 83 x 53.5 mm | 2 mm larger bore |

| Compression ratio | 14.0:1 | 14.0:1 | To the moon! |

| Peak power (at release) | 157.5 kW / 214 hp @ 13000 rpm | 125 kW / 170 hp @ 10500 rpm | A lot more peak power on the sport bike |

| Peak torque (at release) | 124 Nm / 91.5 lb-ft @ 10000 rpm | 125 Nm / 92 lb-ft @ 8750 rpm | Similar torque that peaks lower on the Granturismo |

| Valve return | Desmodromic | Spring | First Ducati with spring return since before I was a twinkling in anyone’s eye |

| Rev limiter | 15000 rpm | 11500 rpm | Much lower in the Granturismo |

| Valve service interval | 24000 km | 60000 km / 36000 miles | Much longer in the Granturismo |

The spring valve return in the V4 Granturismo is really a very important note. Ducati has made a lot of fuss over the years about why it uses Desmodromic timing, saying they need it for high engine speeds, or to control steep valve angles on large valves in their latest superbike motors.

For example, in the press release for the 1199 Panigale, less than a decade prior:

“Never before has Ducati’s unique Desmodromic system been so vitally important. With the high engine speeds at which the Superquadro operates, combined with such large valves, it would be impossible for the valve’s rocker-arm to follow the steep closure profile of the cam lobe using normal valve closure springs.”

OK, we get it, Ducati. It was a very powerful V-twin. And you’re special and do things a special way.

But when launching the Multistrada V4, Ducati seems to have accepted that maybe spring technology has caught up, as many other manufacturers have discovered a very long time ago. In fact, Ducati has gone to the other extreme, implying that they worked so hard on extending the service intervals for the Desmo design, that when using a simpler spring design, they can now have the longest service intervals in the industry of 60000 km or 36000 miles — or “one and a half times around the planet”.

Yes, that looks complicated. But it does look simpler than the system of rockers that the Desmoquattro-onward design involved!

By the way, I want to point out that there are still some motorcycles with longer valve service intervals — those with hydraulic valve lash adjusters, like many Harley-Davidsons. Even the latest liquid-cooled, high-power motorcycles, like the Pan America, don’t have any required valve service. Technically, those service intervals are even longer, as they’re infinite.

As for where else the V4 Granturismo engine will end up — I don’t know. A Ducati Monster V4? Ducati Supersport V4? It might also have smaller-capacity variants! Time will tell, and I look forward to finding out.

Ducati Superquadro Mono (2024+)

Ducati announced the Superquadro Mono engine in late 2023, for use in their Hypermotard 698 Mono, a lightweight street-legal single-cylinder supermoto.

See here about all the ways in which the Hypermotard 698 Mono is different.

The Superquadro Mono engine is derived from the Superquadro engine in the 1299 Panigale, and inherits the same 116 mm piston bore, plus the same combustion chamber, titanium inlet valves, steel exhaust valves, and Desmodromic valve control system.

| Item | Ducati Superquadro Mono spec |

|---|---|

| Engine design | Single cylinder, DOHC, 4 valves, Desmodromic timing |

| Capacity | 659 cc |

| Bore / Stroke | 116 x 62.4 mm Bore/stroke ratio of 1.86 |

| Compression ratio | 13.1:1 |

| Peak power | 56.6 kW / 77.5 hp @ 9750 rpm (62.1 kW / 84.5 hp @ 9500 rpm with Termignoni exhaust) |

| Peak torque | 62 Nm / 46 lb-ft @ 8000 rpm |

| Maximum engine speed | 10250 rpm |

| Service intervals | 9000 mile / 15000 km oil change 18000 mile / 30000 km valve service |

Other cool facts about the Ducati Superquadro Mono:

- Piston pin has DLC coating (similar to in V4 R), as do rocker arms

- Desmodromic valves are driven by a mixed gear/chain system

- Ride by wire, via a single 62 mm throttle body

- Aluminium crankcase (similar to the 1299 Superleggera)

- Magnesium alloy clutch, alternator, and head covers

- Weight balancing via asymmetrical crankshaft and two balancing countershafts

While the Hypermotard 698 is the first motorcycle to have the Superquadro Mono engine, I don’t think it’ll be the last.

Sum up

As usual, this “quick explainer” ballooned out into a thesis article.

Hopefully, that was clear. If there’s anything worth adding or clarifying, let me know.

Your first specification of the 750 GT of ‘71 states cam drive by belt. This is false. The bevel gear tower shaft was used for the early models till the Pantah based engines.

Hi Karl, thanks for that correction, and I made the update. I saw the original Pantah a few weeks ago in the Ducati museum, and will add a pic!

Hey Dana

A comprehensive article, although I’ll point out a couple of errors.

– Your ‘Desmodromic 2 valve diagram’ incorrectly identifies the opening and closing rockers.

– You say that Ducati for years has used a ‘shim under bucket’ arrangement; shims, yes, but not buckets.

Cheers

Mark

You meant to say “Updated in Nov 2023…” right, else if you’re updating from the future tell us how the 698 is like already!

Updated the updated comment!