This is a document I’m creating as a master repository for understanding motorcycle specs of motorcycles — brake discs, calipers, lines, and so on.

In the past, whenever I read the spec sheets of a motorcycle, I’d be overwhelmed in terminology. One part of this is the motorcycle brake specs — they were meaningless to me with no explanation or context.

So I’m creating this document as a universal reference to understand all spec sheets for motorcycle brakes.

In this guide I’ll cover:

- Single discs vs dual disc brakes (or drums)

- Floating discs vs partially floating discs vs fixed discs

- Axial mount vs radial mount calipers

- Monoblock / monobloc vs other constructions

- Four piston vs two-piston calipers (or six piston or single piston)

- Brembo, Nissin, Tokico, Hayes, and other brands

You might also like my guide to motorcycle forks. This is another article in the same vein.

“Caliper” or “calliper”? The former is US spelling, and the latter is British spelling. I’m a somewhat British Australian who has lived in the States, but I also recognise language is for communicating, and there are more Americans and there’s more American-influenced English anywhere in the world, so I write “caliper”. I do tend to write “tyre” though, because “tire” to me looks like a verb describing how I feel about having to think about this.

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

Why Understand Your Motorcycle Braking System?

Firstly, understanding brake specs is important because it helps with buying bikes — used or new, cheap or fancy.

One area of motorcycle spec sheets I always used to find mysterious is the braking system. I realised this the first time I went to a dealer a few years ago and he was explaining the difference between two models of Triumph Street Triple (the R and RS) that both had Brembo brakes. “Well they’re both Brembo,” I said, knowing the brand is synonymous with quality. “Yeah, but this one’s better,” he said vaguely.

Here’s my Triumph Street Triple buyer’s guide if you want to see how they all compare in everything (engine, brakes, suspension)…

The problem with spec sheets is that they’re hard to parse out of context. If you read “four-piston calipers that grip 298 mm discs”, it’s hard to know what that means unless you know what it could be — what higher- or lower-end bikes have, what bikes had in the past, and what competitors have.

Apart from understanding brake specs for a bike you’re trying to buy, it’s also important for understanding when a brake system has been modified. If you hear that the calipers have been upgraded to Brembo ones, you should be asking things like “but which Brembo calipers?” and know whether they’re necessarily better, or perhaps just different.

One final reason why understanding brake specs is important is that, like suspension, they’re going to stay the same as more electric motorcycles come onto the market over the next few decades. In fact, the latest electric motorcycles from Harley-Davidson, Energica, and Damon all have Brembo brakes identical to those of the latest sport and superbikes.

How brakes work

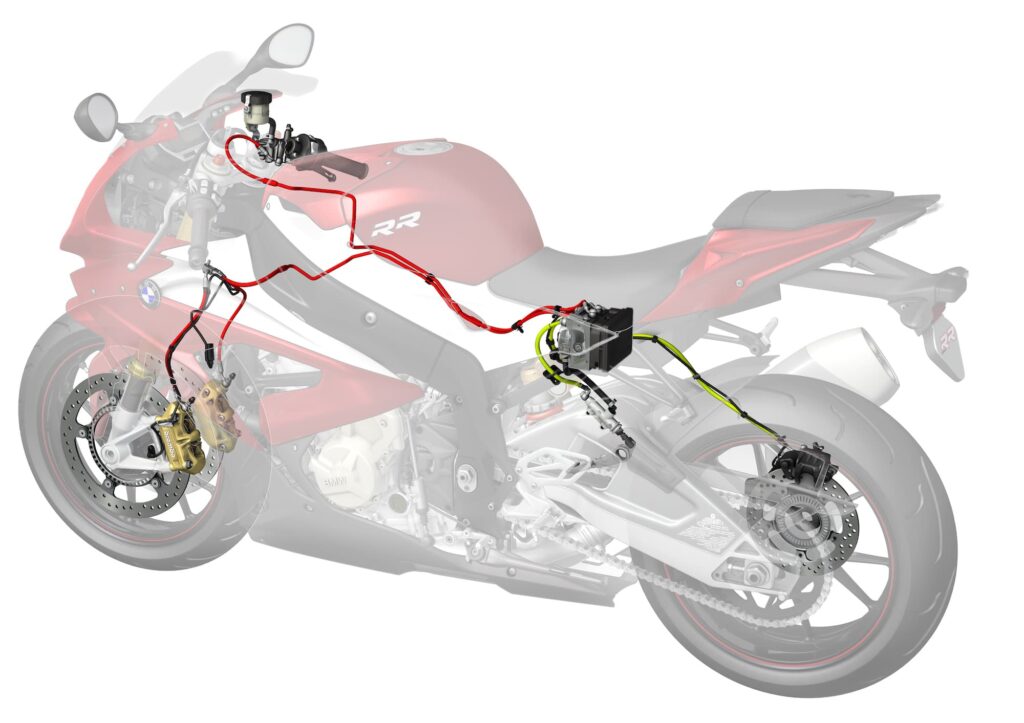

Most people know how brakes work in a general sense. In most cases, you squeeze on the brake lever or step on the pedal. This moves brake fluid through the hydraulic system which then squeezes pistons in the brake caliper onto a disc, which slows the wheel rotation.

But there’s one detail that I want to make clear: the brake system is an energy absorption and dissipation system. Brakes absorb the energy that’s “stored” in the kinetic energy of the motorcycle, including the speed of the bike as well as the rotational energy in the wheels.

Where does the energy go when you use brakes? It converts to heat! The brakes get hot and dissipate the heat into the air. It’s “wasted” in that sense. (Electric vehicles like the Harley-Davidson LiveWire have some tricks to re-absorb the energy via regenerative braking.)

And in case you’re wondering where the energy came from in the first place — it came from the engine. When you drive the motorcycle forwards, you take energy from the fuel (or battery) and convert it into kinetic energy. How quickly you can transfer the energy into momentum is the definition of power.

We talk about the power of a bike as being in kilowatts or horsepower. Both of these describe how much energy the engine can give to the bike per second.

The unit of stored energy is a joule (or a calorie, in imperial units). As you know, there are many kinds of energy — in this system, there’s mainly mechanical energy and heat energy. Energy in joules or calories can be described in two ways:

- How much energy is conveyed by a unit of force over time, or

- How much energy is needed to increase the temperature of certain object

Energy can also do other things, but “mechanical energy” and “heat energy” are the relevant ones here.

When you run your engine, you change the potential energy in fuel (or a battery) to mechanical energy, which is stored in the movement of a vehicle and its wheels (rotational energy).

To stop the vehicle moving, we hit the brakes. That converts that stored movement energy into heat.

The heavier your bike is or the faster it’s moving, the more energy you have to dissipate. In fact, kinetic energy is proportional to the square of velocity.

- Kinetic energy = ½mv2

So it takes roughly twice the energy to slow a bike that’s going 100 mph vs one that’s going 70 mph. And to slow a bike going 140 mph would be twice as much again — or four times as much energy as needed as one going 70.

This is why brakes on bikes that go very fast and need to brake often have to be very good at dissipating heat. But more nuance on that below.

Note — the concept of kinetic energy is unintuitive. Yes, to get a vehicle to move twice the speed, it needs four times the energy (i.e. you spend three times the energy to get from Speed A to Speed 2A as you did to get from zero to Speed A). But this is a topic for another time.

Brake Technology in a nutshell: What are we trying to achieve?

A lot of the below technology is best understood if you look at it through the lens of what constitutes a “good” braking system. What are manufacturers trying to achieve when improving brakes on newer or higher-end motorcycles?

In a nutshell, a braking system needs to be

- Good at stopping (duh)

- Predictable in all conditions (even after heavy usage, wear, in the wet, etc.)

- Light weight

- Low rotational inertia

- Low cost

So all braking systems are a balance of the above. More detail on some of these below.

Goal 1: Good at stopping

A braking system has to be good at stopping the bike.

This means not just stopping any old bike, but

- Stopping this bike — with this weight, and this weight distribution

- Stopping it at the speeds the bike is likely to go — braking from 150 mph or 220 km/h to a standstill is different from braking at commuting speeds

- Stopping the bike and all its accessories and passenger/pillion

Brakes work in concert with the chassis, suspension, and tires, to wipe inertia away from the bike. Generally, when a mechanic tests a braking system on the road, they bring the bike up to speed and then gradually squeeze on the brakes and measure the maximum g-forces they can get out of the system.

As a general idea

- Everyday heavy braking is about 0.5-0.75 Gs

- Maximum braking by a competent rider in good conditions is about 1G

- Maximum braking in racing by MotoGP riders is about 1.5-2Gs

Anyway, a good braking system should let a rider get maximum braking effect.

Goal 2: Predictable in all conditions

In stopping or slowing your motorcycle, your braking system has to deliver on two fronts: a) stopping quickly, and b) stopping predictably.

You hear motorcycle reviewers (or sometimes regular humans) talk about brake “bite” and “fade”. These have somewhat intuitive meanings. Bite means that feeling of “grab”. A lack of “fade” means performing well even after harsh usage, like on the track, where there’s a lot of braking from high speeds.

The way in which you describe the performance of a break system is intuitive. You want brakes where:

- You squeeze the brakes a bit and you slow a bit,

- You squeeze the brakes a lot and you slow a lot, and

- It does the above whether hot or cold, whether you’ve used them a little or a lot, whether the pads are new or old.

Even though it’s hard to deliver on all these promises, brake manufacturers try. Generally, you achieve the above by having sophisticated materials, and rigid components that adjust automatically and can cope with large amounts of stress.

There’s always a degree of compromise. For example, brake pads with great bite and fade resistance tend to be harsher on the rotors, which are more expensive to replace. Or brakes that are very predictable are just more expensive components to acquire.

Goal 3: Low brake system weight

An important aspect that brake manufacturers try to improve is lightness.

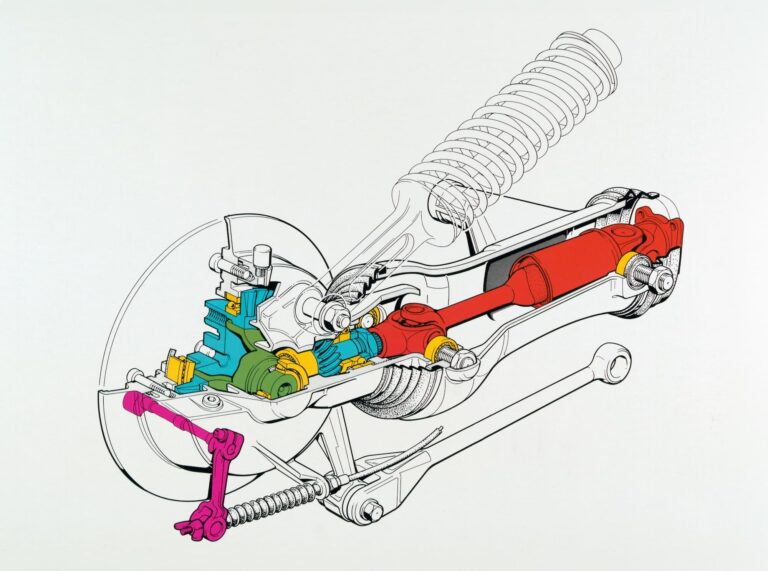

Because the brake calipers sit on a rotor that’s attached to the wheel, it all forms part of the “unsprung mass” of a motorcycle.

I explain unsprung mass in more detail here, but in a nutshell: unsprung mass is the weight of everything on the bottom side of the suspension that moves. Unsprung mass includes the rim, tyre, brakes, and the bottom part of the suspension (whether it’s inverted or “right side up”).

You optimise unsprung mass because the lower the mass of that bottom bit of the motorcycle, the easier it is to change the velocity of that part (go from moving down to moving up, and vice versa), which means the easier it is to stay in contact with the road. Lower unsprung mass = better traction, therefore better handling.

In the world of unsprung mass, things are measured in often just hundreds of grams (or fractions of pounds). By improving brake caliper and rotor design you can get the same stopping effectiveness with lighter components, and stay in contact with the road for longer.

Goal 4: Low brake system rotational inertia

A further goal of advanced braking systems is to minimise rotational inertia (also known as the “moment of inertia”).

Think of rotational inertia as being how hard it is to start something spinning, stop it spinning, or change the axis on which it’s spinning (all of this is to accelerate the rotating object).

More simply, if your wheel + brake disc is very heavy it’s:

- Hard to start it spinning

- Hard to stop it spinning

- Hard to lean the bike (this is the less intuitive bit)

Think of the wheel + brake disc like a flywheel. A flywheel is a spinning disc that stores energy in it. The bigger and heavier it is, the harder it is to change anything about the way it’s moving.

We can decrease the moment of inertia of something by

- Reducing its mass, or

- Moving the mass closer to the middle.

In brake discs, we reduce moment of inertia by keeping the heavy parts of the brake disc in the middle, and making the outside part lighter — using lighter materials and by perforating the disc (which also helps with heat distribution).

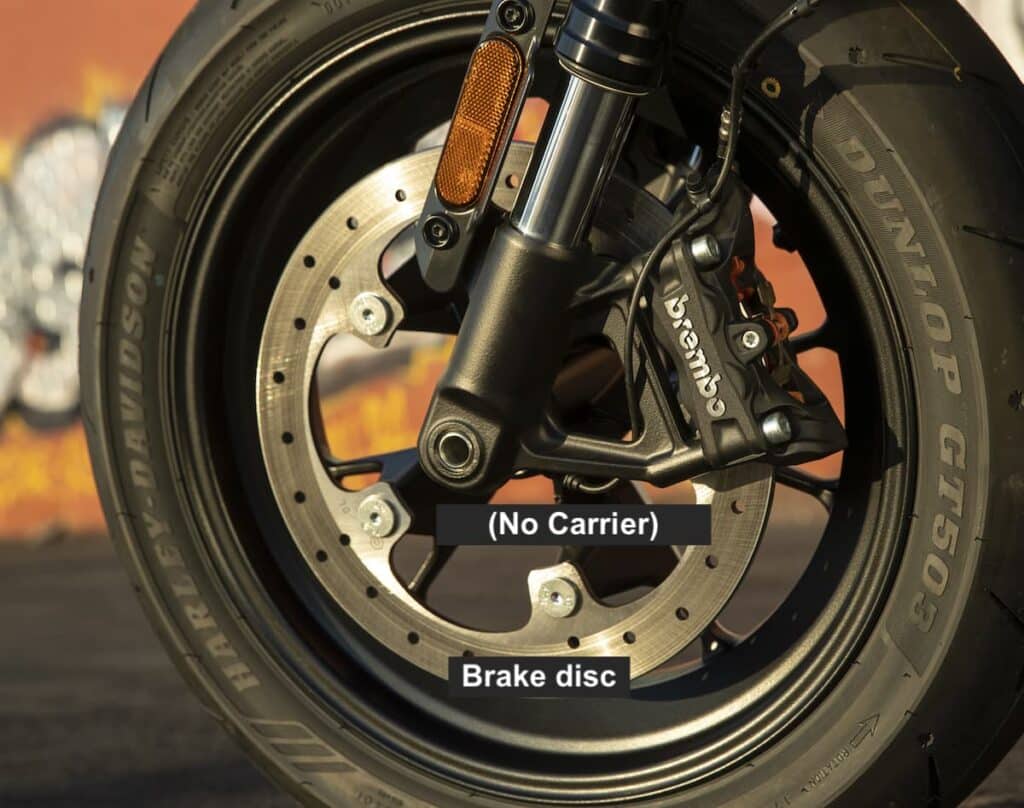

This is why brake discs on modern sportbikes are often made up of a separate, lightweight rotor on a heavier, stronger carrier. (This lets people do other things too, like use floating rotors.) On more traditional cruiser bikes, the brake disc might be just one big solid bit of steel.

Or on the 2021 Sportster S, the disc is bolted directly onto the wheel.

You can also keep moment of inertia down by having just one brake disc instead of two (as do many cruisers and commuter bikes).

Goal 5: Low cost

Naturally, a brake system also has to be low cost, or to fit the budget of the motorcycle in question.

Main components of a braking system

There are eight (by this count) main components of a braking system, all of which merit explaining separately.

But mostly, in motorcycle specs, only the disc, calipers, and braking aid system are mentioned. For example, you might read “Twin 300 mm discs, Nissin 4-piston radial-mount calipers, 2-channel ABS”. More on this below.

| Part | Description | How mentioned in spec sheets |

|---|---|---|

| Brake lever / pedal | Where you do the squeezing or pressing. Nobody worries much about the brake pedal. But the brake lever gets attention for being non-adjustable or just unattractive. High-end bikes come with adjustable levers at least as an option. | Only mentioned if the lever is adjustable, or special in some way |

| Brake master cylinder | Converts leverage pressure into fluid pressure that goes through the cable. A high-quality one lets you get more braking force with less pressure, and operates more predictably. | Only mentioned if upgraded vs the predecessor, or a special design or brand. |

| Brake management system | If anything, ABS or cornering ABS | Usually mentioned only if present. |

| Brake fluid | Transmits the action of the lever to the pistons. Its job is to communicate the pressure without buckling under it. Brake fluid is pretty standard, but it’s part of the system. | Not mentioned in specs |

| Brake lines | The rubber hoses or braided steel brake lines. Rubber ones need replacing, others much need less frequent replacing. Each has a different “feel”. | Only mentioned if braided. |

| Brake calipers | The most important part — this does the squeezing, like a killer robot hand grasping the discs betwixt forefinger and thumb, squeezing it to death. | Usually mentioned as being radial-mounted or monoblock construction (if the case), as well as brand and number of pistons. |

| Brake pads | The friction material that makes contact with the disc. “Where the rubber meets the disc” | Sometimes mentioned in specs as sintered or semi-sintered. |

| Brake disc | The part that’s attached to the wheel onto which the pads grab, the most visible part. | Diameter mentioned, sometimes thickness, and maybe another spec like its style (wave or other), and if it’s floating/fixed. |

Then there are other, less critical (as in not core to stopping the bike) parts of motorcycle braking systems, like

- Microswitches to pick up when a lever has been actuated

- Brake lights at the rear

- Pressure sensors to detect faults

These are of course important for safety and regulatory purposes, but they’re not part of the system that stops the bike.

Reading motorcycle spec sheets or press releases, you’re likely to see descriptions of the calipers and discs — but no description of anything else.

For example

- The original 1993 Honda CBR900RR has dual 296 mm discs and 4-piston calipers

- The 2022 Honda CBR1000RR-R has dual radial mounted four-piston calipers with fully floating 320mm discs with cornering ABS and standard braided brake lines.

- The Harley-Davidson Sportster has a single 320mm rotor and a radially-mounted 4-piston Brembo caliper.

The important thing here is that manufacturers don’t mention when something is missing or a lower spec. For example, manufacturers rarely say “this bike has axially mounted brakes”. That’s the standard way of mounting calipers. They usually only mention it when they’re radially mounted. If they don’t mention it, you’re left guessing (assuming) that they’re axially mounted — but you might be wrong.

Major brake caliper brands

Something manufacturers often mention is the brake caliper. But what does this mean?

Let’s start with the biggest ones. By far the two most well-known manufacturers of brake calipers are Brembo and Nissin.

Firstly, just because a brake part is of a certain brand, it’s not necessarily the best. Brembo brake calipers aren’t all the same level — technology has changed over decades. And sometimes a brake caliper from one brand is better than that of another for reasons best described by testers and racers.

Nobody would say “no” to a motorcycle on the basis of it having Brembo brakes. They might grumble if a bike doesn’t have Brembo calipers, though — that’s Brembo’s brand power!

Brembo has a reputation for producing high-quality components. But look one level deeper and think: which model is it from that brand? And is it necessarily the best? And to which model from Nissin (or another brand) are you comparing it?

You see both of these caliper brands on high-end motorcycles. But you generally see Brembo calipers on high-end and even mid-range European motorcycles, and you see Nissin calipers of various spec on both high-end and mid-range Japanese motorcycles.

Brembo is an Italian brand. It has been around for over 60 years. Brembo has a number of subsidiary brands, including SBS, known for brake pads and discs, and Marchesini, who make lightweight wheels. There are also other sub-brands that focus on racing, or on low-capacity motorcycles and scooters.

Nissin is a Japanese company, the largest shareholder of which is Honda. It’s less public about its operations, but you see the word Nissin in many spec sheets for bikes. But even Honda uses high-end Brembo brakes on its top superbikes, like the 2021 Honda CBR1000RR-R SP, which has Brembo Stylema calipers.

What’s interesting is that Brembo has branded itself as a high-end brand, whereas Nissin makes a range of calipers.

Types of Brembo calipers

Brembo has been making brakes for a long time and for a wide range of motorcycles.

So it’s not enough to know that the brakes are “Brembo” (though it’s a good start). The same goes for any other brand. But Brembo tends to brand its calipers as individual products so you can differentiate between them by name.

Some common types of brake calipers that Brembo has made or does make are:

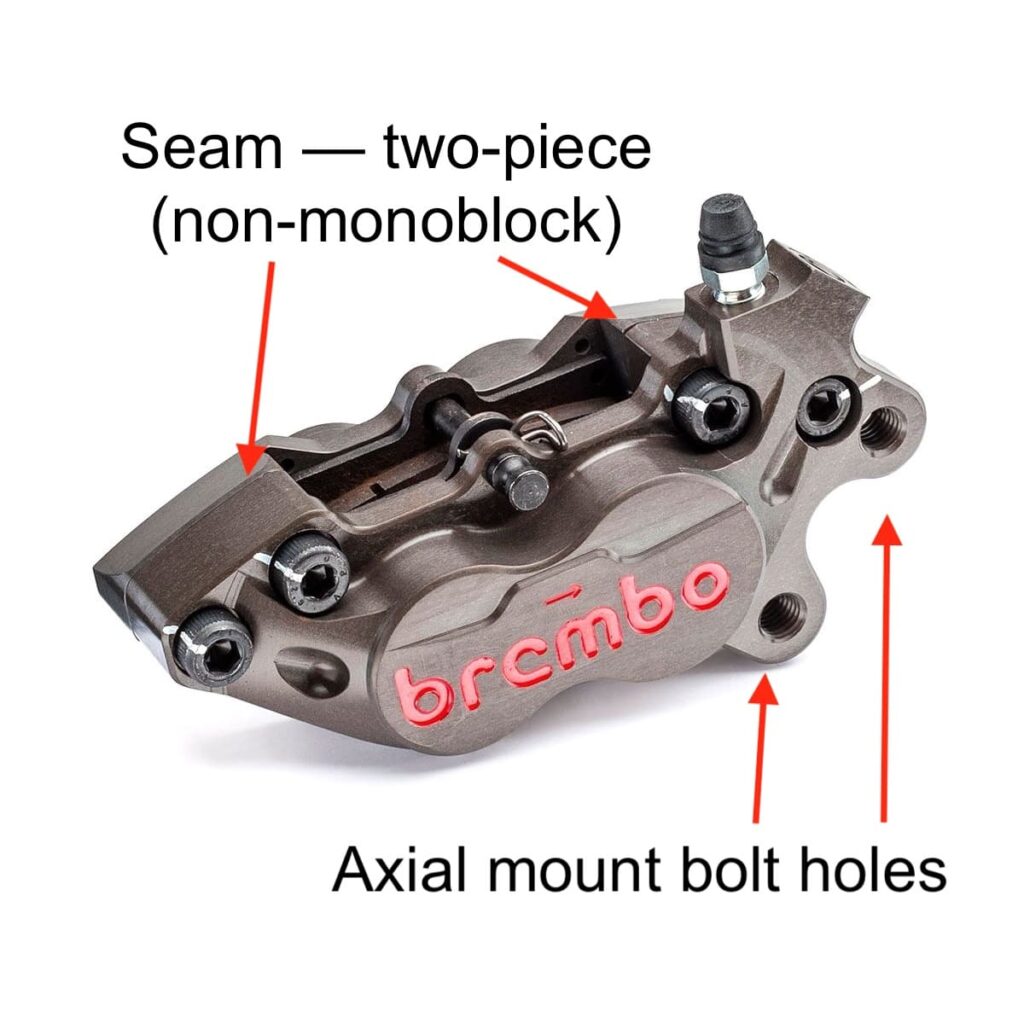

- Brembo P4: Axially mounted 4-piston calipers. Axially mounted two-piece caliper. Available in a few configurations (e.g. 32, 30/34, etc.). Standard on many Ducati motorcycles.

- Brembo M4: The first monoblock calipers with 4 x 34mm pistons.

- Brembo M4.32: Monoblock radial-mount 4-piston calipers with four x 32 mm pistons (hence the code). You see this on mid-range sportbikes like the BMW R nineT, Triumph Street Triple R, and even the Suzuki GSX-R1000.

- Brembo M50: Monoblock radial mount calipers with four 30mm pistons. We first saw these as original equipment on the Ducati 1199 Superbike. Great stopping power but lighter weight than the M4.32. You see this on the Triumph Street Triple RS, 2017+. The number “50” in “M50” refers to the number of years Brembo had been in business when they released the calipers. Used on a wide range of high-end bikes like the Street Triple RS, Kawasaki ZX-10RR, and, interestingly, on the humble CFMOTO 700 CL-X.

- Brembo Stylema: Lightweight calipers with 4 x 30mm pistons. Focuses on more efficient cooling through air passage design, and also reduced weight by 7% vs the M50 calipers. Seen on the Ducati Panigale V4 and KTM Super Duke R.

- Brembo Stylema R: Even higher spec Stylema brakes.

It’s not always obvious which Brembo calipers are in a motorcycle (if the marketing materials don’t mention it). But absolutely don’t assume that the calipers on your mid-range standard are the same as those on a high-end superbike.

Smaller brake brands

Other manufacturers of calipers you’ll see in spec sheets (of the past, or present for ByBre) include:

- Tokico — A Japanese motorcycle parts brand now owned by Hitachi. You see many of these on Japanese motorcycles.

- Hayes — Acquired by Brembo in 2007, Hayes is an American brake parts manufacturer that even once owned a part of Brembo. They briefly made brakes for some BMW motorcycles in 2021, but then they were pulled due to leaks.

- J.Juan — A Spanish Barcelona-based brand. Brembo acquired them in 2021. They make parts for some motorcycle manufacturers. For example the brake lines on my BMW R nineT are J.Juan, and the brake calipers on the latest high-end Zero electric motorcycles are by J.Juan too.

- ByBre — A brand owned by Brembo that focuses on brakes for scooters and small-displacement bikes, including the KTM 390 series. All manufacturing is done in india.

If calipers are made by one of the above manufacturers, they’re not necessarily “worse”. They don’t carry the prestige of Brembo (or high-end Nissin) calipers, though.

Floating vs. Fixed Discs (and Calipers)

Manufacturers of brakes or motorcycles often describe brake discs as being floating or semi-floating.

This sounded alarming to me. Knowing that one of the goals of building good braking systems is rigidity, I couldn’t imagine having something floating as it seems “loose”. But it’s quite the opposite — a floating system self-adjusts and minimises tolerances.

Manufacturers also sometimes say they have a floating or fixed caliper. But this is where things get tricky, because

- Floating discs are better, and “fully floating” are even better, but

- Floating calipers are not as good!

Standard (Rigid) brake rotors

A standard brake disc is rigid and stays fixed to the wheel of a motorcycle.

Below is a photo of a conventional brake rotor. It is made of a solid piece of steel. You’ll see these on older motorcycles, and some newer ones (like cruisers), particularly more “traditional” designs.

A solid steel brake rotor does its job fine. But it has some disadvantages. Primarily, the middle part is made of steel when it doesn’t need to be, so it’s unnecessarily heavy.

Secondly, since the whole thing is made of one piece of metal, it’s very susceptible to warping. As it gets hot, the whole brake disc can flex, pulling against the rivets that bolt it to the wheel.

The intermediate solution to the problems of a solid steel brake rotor are the two-piece brake rotor, also known as the semi-floating disc.

Semi-floating rotors

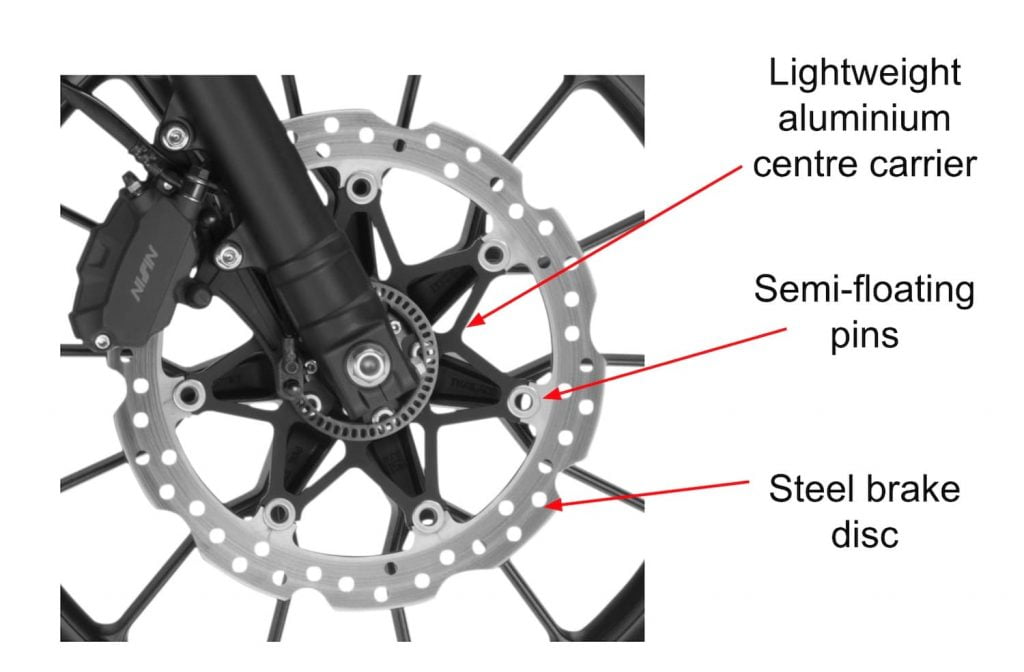

Most modern motorcycle brake discs — even those on economical motorcycles (like a Honda CB500X, whose front disc is pictured below) — are “semi-floating”.

Semi-floating sounds pretty good, right? It’s halfway to full floating! But actually, semi-floating is almost a design requirement of having a two-part caliper.

Manufacturers make two-part calipers because a) they weigh less (meaning less unsprung mass, which leads to better traction), and b) they’re warp less.

A semi-floating brake rotor is made of two parts — a center carrier, usually made of an alloy, and the steel disc.

Because the center part of the brake disc is now an alloy, it’s much lighter. Sure, we’re measuring in grams here, but weight is much more important when discussing a) unsprung mass (mass below the suspension), and b) rotational inertia or energy.

A second benefit of a two-piece semi-floating rotor is that it warps less.

When you brake onto the steel ring, it gets hot. But that heat doesn’t transfer as easily to the alloy centre because it’s disconnected at the point of the rivet. Thus, while the outer steel ring can still warp, it won’t warp all the way to the centre where the disc is connected to the wheel at the bolts.

So why is the two-part disc “semi-floating”? It’s because this is a design requirement of connecting two different kinds of metal.

Aluminium alloys and steel each respond differently to heat. They expand and contracts at different rates.

This means that if you try to weld or braze aluminium and steel together (which, as a reader pointed out, isn’t possible), heating them up a lot would cause them to expand at different rates, and break apart. Thus, you have to connect them by rivets and give them room to move.

The centre aluminium carrier and outer disc can thus expand and contract at different rates without breaking off from each other.

But a semi-floating disc isn’t self-adjusting. There’s a chance the pads could wear unevenly and apply different amounts of pressure to the disc on each side. So to counter this, you have to either have

- A fully floating brake disc, or

- A floating caliper

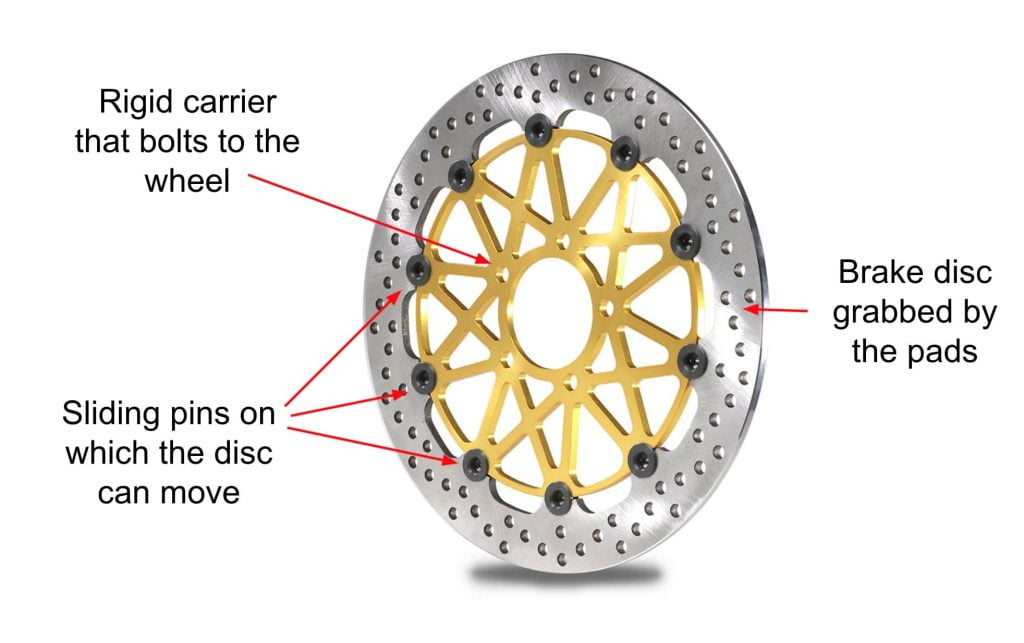

Fully floating brake discs

A floating disc is like a semi-floating disc in that it is made of two parts — a lightweight carrier and a steel part that moves on it.

But unlike the semi-floating disc, the outer steel part can move laterally too (a very short amount) on the pins that hold it in place.

If you have a sportbike of some kind (e.g. a 600cc-class bike or literbike), you may have fully floating pins. Grab the disc and wiggle it from side to side. If it moves laterally by 0.5-1.0mm, then you have a fully floating brake disc.

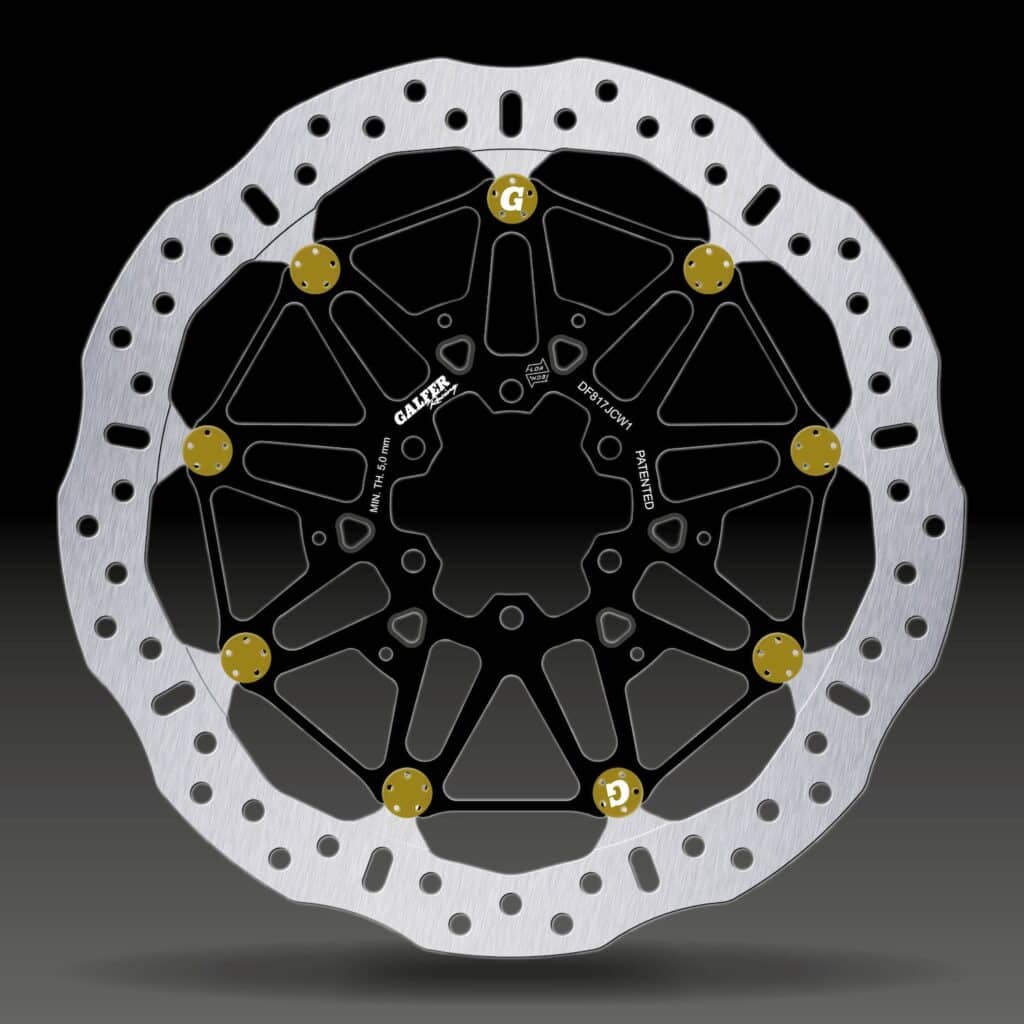

See this below image of a fully floating Brembo brake disc:

This design has several advantages over a rigid brake disc.

- Automatic alignment. Because the disc floats, it can keep itself aligned between the brake pads. This means that the pads will be more constantly in contact with the rotor

- Better prevention from warping. Because the unit can warp, a floating disc is more resilient against being pulled out of shape and warping under extreme heat and pressure.

Then you look at the above and you think “That looks heavy and has many points of failure!”

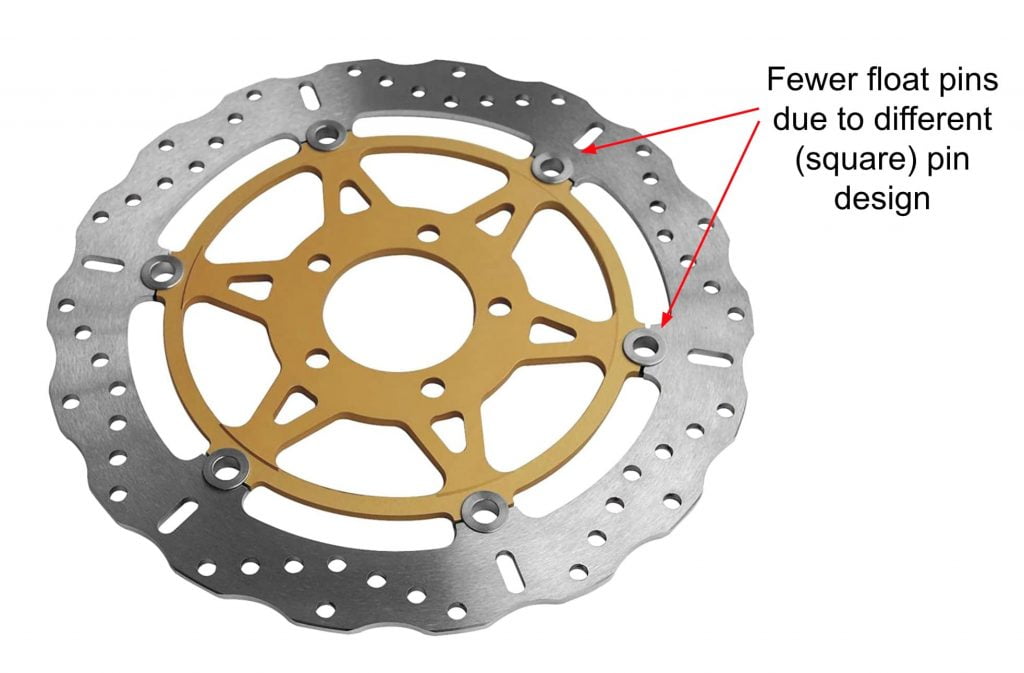

There are other designs of fully floating brake rotors, like this one from EBC. It has only five pins and they’re of a square design when you take it apart.

Are floating discs always better?

Short answer: no.

Because there are more points of failure, sometimes it’s better to have a simpler design. If you’re not chasing lightness or riding a high-performance bike, then a fixed disc may work just fine. You may never work it hard enough to warp it, and then when you do, it’s not expensive to replace.

A second place where fixed discs are better is in heavy-duty off-road applications. For example, see this Honda CRF450R’s front brake disc setup.

Offroad and motocross bikes have lightweight discs that are not floating. They may be perforated and wave-style, to increase heat dissipation, but they won’t be floating.

The reason for this is that off-road riding means lots of dust and debris. A non-floating design means there are fewer places for the dust and debris to get into, and more resilience to impact from flying debris.

Are floating / sliding calipers good?

I used to find this confusing, so I think others might: high-performance brakes means fixed calipers, not floating. This is the opposite of the rule for rotors.

A floating caliper has pistons on one side of the caliper, and simply “pulls in” the pads on the other side. Then when you release the brake, they both separate from the brake disc — assuming the system is well-lubricated.

So in theory, you can use a floating caliper on a fixed disc, and to a degree it’ll self-adjust.

Many modern but lower-spec motorcycles have floating calipers. For example, the latest Triumph Bonneville T120 has floating two-piston calipers on a solid steel disc. These aren’t bikes designed to be hustled along quickly.

The benefit of a floating caliper is that it has fewer moving parts, fewer points of failure, and thus it’s cheaper to make.

A secondary benefit is that it does self-adjust with respect to the rotor.

But the downside is that you have fewer pistons so less braking pressure.

Monoblock (vs two-piece) Calipers

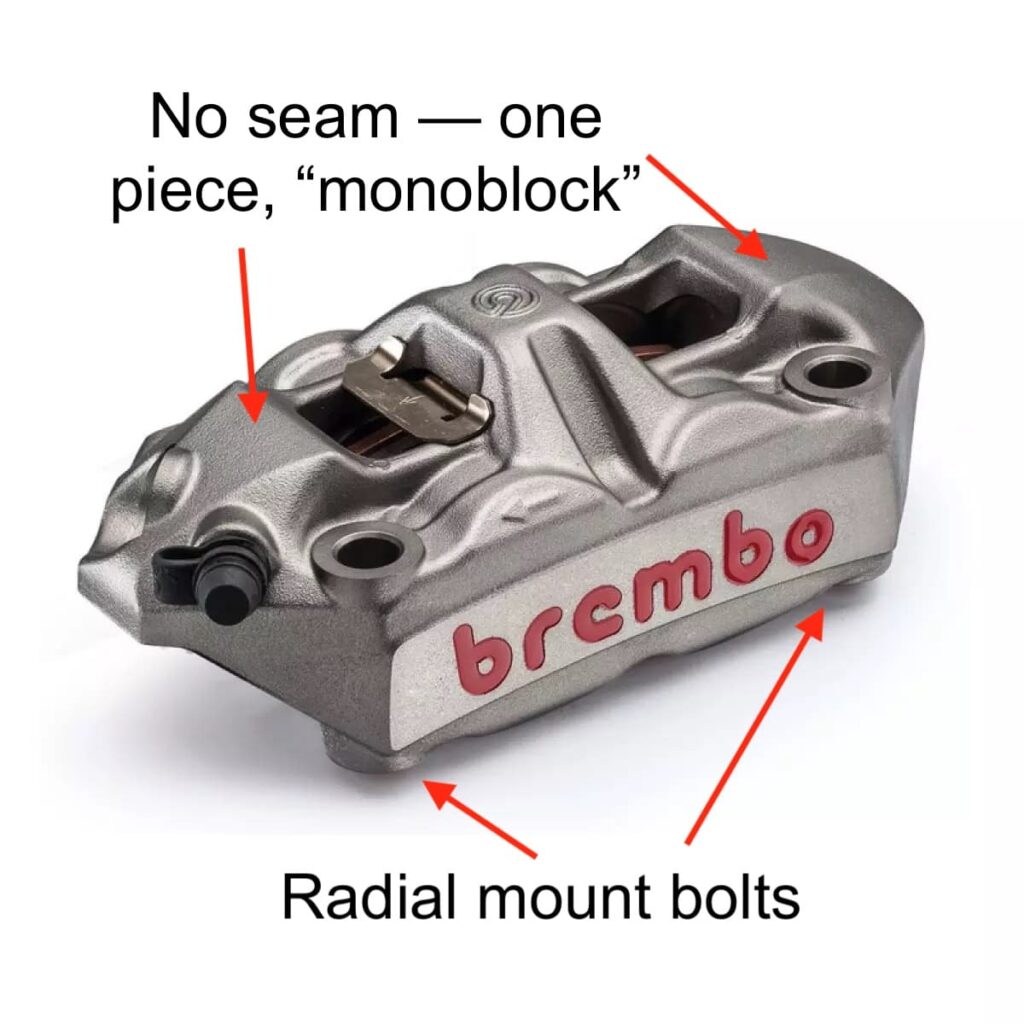

The type of brake caliper used is an important part of a braking system. These days, brake calipers on many high-end bikes are described as “monoblock”. If they’re not described as such, they’re likely not built from a single piece.

A brake caliper is described as monoblock (or monobloc) when it’s made out of one piece of metal. This was first invented by Brembo, and first appeared on a production bike in 2006. These days, it’s pretty common even on mid-range bikes — even the affordable (but great) Honda CBR650R has monoblock calipers.

Before monoblock/monobloc calipers came along, calipers were just called calipers. After the advent of this style of caliper, we refer to the old style as “two-piece construction”.

Look at the construction of a conventional multi-piston caliper, like the Brembo P4 above. Since it squeezes in two pads — one from either side — it needs two “faces”, each with pistons to do the pressing.

The easiest way to do this is to make two halves and bolt them together, creating what’s sometimes referred to as a two-piece caliper.

On many older brake calipers you can see a seam in the middle holding the caliper together.

When the pistons press in against the brake disc, the caliper can flex apart at the seam, which reduces braking effect.

So instead of making a caliper out of two pieces of metal, Brembo decided to make it out of one piece. This achieves two things: a) it’s stronger (doesn’t flex), which leads to more predictable performance, and b) it’s also lighter as it doesn’t need bolts holding it together.

You can also reduce caliper flex by using more pistons in the caliper, or by using bigger pistons — but that’s at the cost of weight. So in the early days of superbikes, a common upgrade path was for a six-piston two-piece caliper to be upgraded to a four-piston monoblock caliper. Just as strong and lighter!

Mounting styles — Axial and Radial

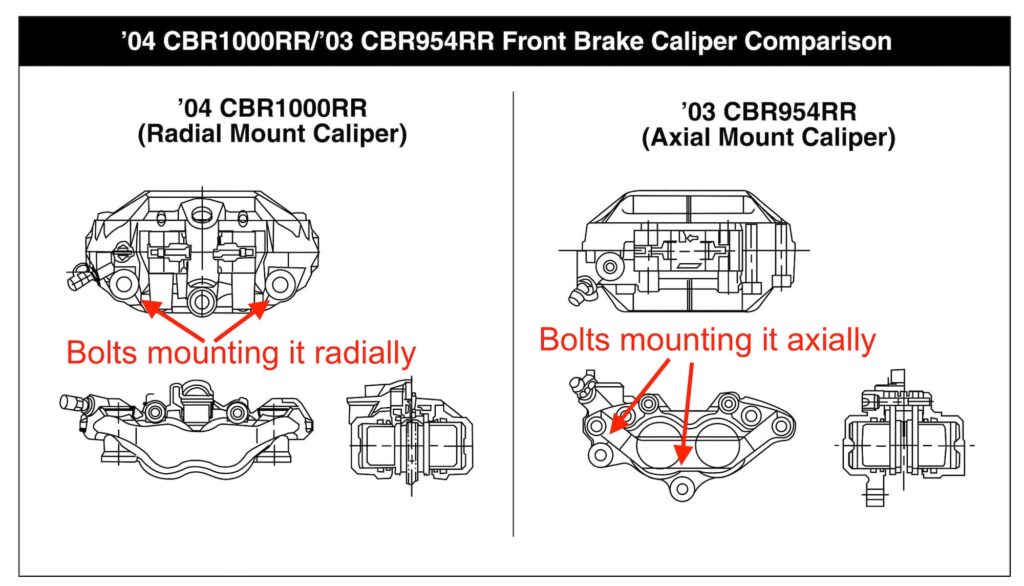

There are two main ways to mount a caliper to a disc — axially and radially. These describe how the caliper is mounted relative to the wheel spokes.

- Axial = the caliper mounting bolts are parallel to the axle of the wheel.

- Radial = the brake caliper mounting bolts are parallel to the radius of the wheel, i.e. the spokes.

Axial mount

This is a traditional way of mounting calipers. It’s still in use, as it’s fine for many lower-spec, cheaper bikes, and it’s cheaper to manufacture. It’s currently on lower-spec bikes, too, that are still in production, like the Suzuki SV650X, or even the 2022 Harley-Davidson Nightster — not a cheap bike!

On an axial-mounted caliper, the mounting bolts are parallel to the axle (going through the wheel).

There’s nothing “wrong” with axial-mount calipers, and they’ll definitely bring you to a hurried stop, until you see the benefits of radial-mounted calipers.

Radial mount

On radially mounted calipers, there is a bolt at the front and rear of the caliper. The bolts are parallel to the radius of the wheel (i.e. they go from the outside towards the axle).

The benefits of radially mounted calipers are

- Better caliper-to-disc alignment. The caliper body is centered over the disc using locating dowels rather than sliding pins.

- More rigidity. The calipers are secured at both ends (not just one, as is common on axial calipers)

The better alignment and rigidity reduces how much the caliper twists when the brakes are applied.

This translates to better feel at the lever and more even wear of the pads.

Brake Rotor design concepts — Wave, Perforated, Solid, and Thickness

Back in the day, rotors didn’t just used to be solid — they were unperforated discs. These days, perforated discs are much more common. And for a while, wave rotors were common (there are some images of wave rotors above).

The purpose of a brake disc is more than just “something for the calipers to grab onto”. They get hot and they have to dissipate the heat. That’s how perforations and waves help — they give the disc more surface area to emit the heat.

The second factor is brake disc thickness. The thicker a brake disc, the longer it’ll last, and the more heat it can absorb.

But the thicker a brake disc, the heavier it is, and the less heat it can radiate.

These days, brake discs are often built to be a very careful balance between longevity, weight, and resilience against warping. Manufacturers like Galfer who sell wave discs wax lyrical about the benefits of wave rotors, but the differences are trivial, and sometimes just cosmetic. See some images of Galfer wave rotors below.

For example, Kawasaki put wave rotors on their high-end and championship-winning ZX-10R superbike for years, but in recent years they’ve gone back to regular circular (perforated floating) discs.

Brake lines — Braided vs Rubber

Brake lines are the parts of the system that hold the brake fluid. They are between the brake master cylinder and caliper, sometimes with some extra routing for the ABS system.

Most motorcycle brake systems for consumer bikes have rubber brake lines, other than sport bikes like 600 or liter-class bikes.

But many even moderately high-end bikes come with braided brake lines. E.g. my BMW R nineT, a sporty bike but by no means a dedicated high-performance bike, comes with J. Juan braided lines.

A common upgrade for a cheap bike that you’re repurposing for the track, something like an SV650 or a Ninja 400, is to replace the rubber brake lines with steel braided lines.

Generally, you replace rubber brake lines with steel braided ones if you want brake lines that don’t flex and are resistant to external conditions (rocks, sunlight, etc.).

In a nutshell, here are the pros and cons of braided and rubber brake lines.

| Factor | Braided brake lines | Rubber brake lines |

|---|---|---|

| Longevity | Long — braided brake lines are very tough | Short — should be replaced every 4 years or whenever you notice cracks or leaks (more often if the bike is stored outside |

| Durability | Tough — abrasion resistant | Not tough, can be damaged |

| Brake feel | Excellent all the time, but can be harsh for casual users | Still great, though it declines as you use the brakes heavily (e.g. on track) |

| Price | Expensive (i.e. ~$100 for a set) (but you don’t replace them often) | Cheap to replace, other than the time of bleeding a brake system |

| Looks | Look “cool” | Look like rubber tubes |

If you’re thinking of replacing brake lines with steel braided ones just for looks or longevity (i.e. not performance), you may as well wait until it’s time to replace all the brake fluid in the system and do it in one shot.

How often should you replace rubber brake hoses?

Here’s what the manual for nearly every motorcycle says, if they come with braided brake lines: Replace rubber brake hoses every 4 years, or sooner if you notice cracks or leaks, or evidence of dried brake fluid.

Sometimes, manuals for some brands don’t mention the four year number. When I speak to mechanics, generally they say: that four year number is quite conservative. It assumes that you’ve abused your bike by leaving it out in the sun every day and that you have ridden in your share of adverse environments.

But the reality, they say, is that you should replace your brake lines as often as they feel “bad”. And that many motorcycle owners who’ve babied their bikes have had the same brake lines on there for many tens of thousands of miles/kilometres, and sometimes decades.

I know, I know. Brake lines are part of safety equipment. You shouldn’t mess with it. Like with tires, brake pads, and other things that can save your life, it’s not a time to be cheap or lazy.

But still, I’m just saying — if you’ve hardly ridden your bike, stored it inside, kept it clean and free of moisture and the brake lines look fine — don’t assume you have to change them at 4 years unless you’re just looking for a job to do.

Brake pads — Overview and Terminology

Finally, you can’t have a discussion of brake performance without talking about the part where the brake calipers actually make contact with the disc: the pads!

Like the rest of the braking system, motorcycle brake pads are designed and made to optimise between cost and performance for a variety of use cases.

The “best” brake pads for track use would be a poor choice for someone who uses their bike for UberEATS deliveries, for example.

Before we go into it, let’s look at a bit of brake pad terminology.

When discussing brake pads, some words get thrown around. Let’s look at what they mean.

- Brake pad bedding in period: When you get new brake pads or discs, you need to go easy on them for a while — for the first 100 km, only plan on braking gently. If you have sintered or track-level pads, you might have to plan on 500 km according to some brake pad manufacturers.

- Brake pad “Bite”: Bite is how quickly brakes “grab”. In technical terms, it’s the speed at which the friction material reaches its maximum friction coefficient. You never want infinite bite. Too little means braking is more difficult or slow; too much means modulation is a compromise.

- Brake pad “Fade“: Brake pads fade when the temperature at the interface between the pad and the rotor goes beyond the thermal capacity of the pad. The pad then loses friction capability. The brake pedal remains firm and solid, but your bike won’t stop as quickly. You also will sometimes be able to smell it when your pads are overpowered.

There are other words that you’ll see, but those are the most common.

Types of brake pads

Let’s go over the types of brake pads and discuss which you might need. Here’s a summary table discussing all the kinds of motorcycle brake pads you can buy, with more explanation below.

Before going into much detail, there’s a couple of general caveats I should make.

Firstly, every manufacturer does things a bit differently. A sintered brake pad from one brand may feel different to another.

Secondly, every rider is different, rides in different conditions, and has different expectations. If you are comfortable with how a sintered pad feels when cold, then you might not agree that it doesn’t have a required warm-up period.

But let’s make it very easy. Here’s my extremely quick buyer’s guide to brake pad types.

| The Brake Pad Matrix | “I ride slowly” | “I sometimes ride quickly” | “I ride quickly” |

|---|---|---|---|

| “I want to spend less” | Organic | Sem-sintered / Semi-metallic | Sintered / Metallic or Ceramic |

| “I’ll spend a lot” | Organic | Ceramic, if you prioritise performance | Sintered / Metallic (or a track-only type) |

Sometimes, of course, you’re limited by what your local manufacturer has. Often, I find that my local bike shop stocks only sintered brake pads.

Here’s more detail below about those types of brake pads.

| Type of brake pad | Pros | Cons | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic | * Softer, more progressive feel; no abrupt “bite” * Low wear on rotors * Quieter * Produce little brake dust | * Fade — perform worse as they heat up; can glaze over * Wear out quickly Lots of dust | Commuters, casual riders |

| Semi-sintered, a.k.a. Semi-metallic | * Moderate feel, wear, noise — in between organic and sintered * Lower noise than sintered pads * Affordable | * Some fade, but only when “pushing it” * Wear out more often than sintered (but not as much as organic) | Experienced riders who ride quickly sometimes |

| Ceramic | * Long life * Low dust (lower than semi-sintered) * Still works at high heat levels | * Expensive * Low feel * Not as good as semi-metallic pads cold | Experienced riders who push it sometimes with more money |

| Sintered, a.k.a. Metallic | * High-performance * Long lasting * Take a while to bed in | * Harder on rotors * Has to be warmed up, but still OK when cold * Noisy * More expensive | Those who ride sport, or go to the track |

All the manufacturers make these kinds of brake pads. They tend to get fancy in their naming, and describe some as “race” and so on, but broadly they fit into these categories.

More detail on each kind of brake pad below.

Organic brake pads

Most people with low to mid-range commuter bikes who ride around in everyday conditions would be ok with organic brake pads.

Organic brake pads are made of fibers/materials like rubber, carbon compounds, glass or fiberglass, kevlar, and so on. They’re held together by a resin. Sometimes they’re also known as “resin” pads.

Organic brake pads are cheap, work from the moment you take off, and are effective in everyday use. They produce dust, so you wouldn’t use them on a bike that you clean often, or one that has white wheels. They also will wear out themselves rather than wearing out a rotor.

But if you start riding aggressively (lots of very fast accelerating and braking), you’ll find the limits of organic pads. They don’t work well as they heat up.

If you ride something like a sub-300cc commuter bike, or any scooter that you use for commuting work, organic brake pads are your best bet. Going to a higher-end pad may extend the life between pads, but they’ll also be harder on your rotors.

Semi-sintered brake pads

Semi-sintered brake pads are a good compromise for many motorcycle owners. They’re somewhere in between organic pads and sintered pads in terms of performance.

Basically semi-sintered pads are a mix of the resin compounds in organic pads and the metallic compounds in sintered pads.

Like sintered brake pads, semi-sintered brake pads have pretty good resistance to fade, and work in a variety of conditions.

You’re only likely to find their limits if you really ride aggressively.

Even though semi-sintered are a good compromise for everyday use, they’re harder to find, as most people just go for sintered pads and are OK with replacing rotors sometimes.

Ceramic brake pads

Ceramic brake pads are supposed to be an alternative to semi-sintered pads, but many users find that they just don’t warm up quickly enough to give much real word usage. They’re not as popular.

Like semi-sintered pads, ceramic brake pads are long-life, quiet, and low-dust — with even less dust than semi-sintered pads, because they don’t have any resin in them.

Ceramic brake pads are also more expensive.

The catch with ceramic brake pads is that even though they handle high temperatures with quick recovery, they have a noticeably non-zero warm-up time — even less so than sintered pads — and don’t grip in a way that many would be comfortable with when cold. So if you tend to do a lot of point-to-point commuting, you might find it frustrating riding away and not being able to stop effectively at the first traffic light.

Because ceramic brake pads don’t feel familiar to many non-racers, they’re not a popular choice for everyday usage.

Sintered pads (a.k.a. Metallic pads)

When asking sport bike riders what kind of pads you should get, they’ll typically recommend sintered pads. In fact, sintered pads are OEM on a wide variety of bikes, simply because they’re fine when cold, and even better when warmed up. Plus, they last for a long time.

Sintered pads are made from metallic particles that are fused together at high temperature and pressure. They work well under a variety of conditions, and work well when they’re wet.

The major downside to sintered pads is that they do need to be warmed up, and they make a bit of noise.

Secondly, sintered pads can be harder on rotors. So you’ll find yourself replacing rotors more often — though we’re still talking in the tens of thousands of miles or kilometers of road use.

One of the most popular kinds of sintered pad is the EBC Sintered HH range. A common piece of advice I see on forums is to just buy EBC HH and stop wondering! They’re also cheap for something so widely recommended — think $50 for a pair of pads.

Generally speaking, the brake pads that ship with sport-ish motorcycles are sintered or semi sintered pads. For other mid-range motorcycles, they’re likely to be semi-sintered pads.

OEM vs Aftermarket brake pads

Most motorcycle manufacturers don’t make their own brake pads, just as they often don’t make their own braking components (hence seeing brands like Brembo, Nissin etc. in descriptions of motorcycle specs).

So when you are after OEM pads, you are probably after a) the brand that it shipped with OEM, and b) the type of pad that it shipped with.

Major brake manufacturers make OEM brake pads for a lot of motorcycles. Even Brembo does, e.g. for motorcycles that ship with Brembo brake calipers.

![Triumph Electric Motorcycle TE-1 Prototype — Final Results [Updated] 26 Triumph Electric Motorcycle TE-1 Prototype — Final Results [Updated]](https://motofomo.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Triumph-TE-1-Electric-Motorcycle-Prototype-rhs-side-view-768x512.jpg)

Thanks Dana for a well written , clearly illustrated and very interesting article about bike’s brakes. I finally don’t need to vaguely guess the meaning of several technical words I regularly encountered in my reading.

Awesome article, as we have come to expect and appreciate from you. Thanks for going so deep on this one.

I’ve owned many bikes and fully agree that Brembo brakes just feel and perform better than other brands. This holds true for both street and dirt. As an example, my 2022 Beta 200 Nissin brakes have nowhere near the feel and fade resistance of the Brembo brakes on my 2013 Husqvarna WR125. The Beta brakes can get “grabby” at times where I’ve never felt this on my Husky. Same with street bikes, my recently sold Aprilia Falco had Brembo 34/30 calipers on 320mm disks that set the standard for both power and feeling. Same with my recently sold Aprilia Futura, unbelievable (Brembo) braking for a sport touring bike.

I’ve gotten nostalgic for my youth, so my current sport bikes include a 1991 Honda CBR600F2 (floating two piston calipers, fixed disks) and a 1990 Honda NSR250SP (fixed four piston calipers, floating disks). I love riding these old bikes, and the NSR braking is much better than the CBR, but still worlds away from modern sport bikes.

Thanks again for an engaging write up, Paul B.

Can u please do a mini-article about master cylinder: size and specs. I would love to wait for it

Good idea, in the works.

This is a really nicely put together article. Thank you for your thoughts!

Thanks Dominick!

If you figure out how to “weld or braze steel to aluminium”, you’ll make billions of dollars.

Yes, true on welding — I clarified that line.