Every few years, the balance of what’s hot and relatively cheap shifts. It usually takes a few years for new bikes to make old ones drop in price as everyone loses interest. But right now, the Suzuki Bandit — particularly the Bandit 1250 and GSX1250FA — are real picks.

Generally, Suzuki tends to update models slowly. They usually keep things around for periods of 5-6 years before making changes other than cosmetic ones, even in popular bikes like their SV650 or the superbikes. And in some cases, they haven’t made fundamental changes in decades.

But it has been a number of years since Suzuki last updated their line of sport tourers. In 2016, Suzuki replaced the old Suzuki Bandit-based bikes with those on the GSX-S1000 platform, like the latest Suzuki GSX-S1000GT sport tourer.

As time has passed, the previous generation of sport tourers from Suzuki, those based on the GSX1250 platform, are now relative bargains. And the Bandit 1200 is still great too, if you want to deal with carburettors, and if you can find one and if it hasn’t been wheelied to an early grave.

So here’s a guide to:

- How the Suzuki Bandit line came about, and how it evolved

- Differences between the different Suzuki Bandits (and the GSX1250FA)

- How they compare to the later generations (the GSX-S, based on the K5 GSX-R engine)

- Alternatives to the Suzuki Bandits

Onward!

Are you obsessed with motorcycles?

Well, I am. That’s why I created this site — as an outlet. I love learning and sharing what others might find useful. If you like what you read here, and you’re a fraction as obsessed as I am, you might like to know when I’ve published more. (Check the latest for an idea of what you’ll see.)

The Suzuki Bandit and GSX1250FA — How did we get here?

No bike exists in a vacuum (although a vacuum does exist in a bike!… I’ll see myself out), so I like to explore a little of historical context to show where every bike fits in with things.

There are many Suzuki bikes with the “Bandit” denomination. They all are generally road-oriented bikes, but they exist in distinct size classes. Here, we’re talking about the “big” Bandit.

I say “big” Bandit because there actually have been a ton of Bandits, large and small, all the way down to the Suzuki GSF250 Bandit, a 248cc liquid-cooled four-cylinder standard sport bike made since 1989. It’s a cracker! Suzuki even released a version with variable valve timing, the Suzuki Bandit 250V.

The first Bandit to make it to the US was the Suzuki Bandit 400 (a.k.a. GSF400), a 398 cc four-cylinder standard sportbike that makes 43 kW / 58 bhp at 12000 rpm. Suzuki released this at the same time as the 250, in 1989.

Like any 400-cc sport bike, the GSF400 Bandit is apparently a barrel of fun, but hard to buy when there’s a bigger one right next to it that your license lets you ride. These days, they’re hard to find.

There are other Bandits, like 600 cc and 750 cc ones. They’re all the same general concept of bike — four cylinders, basic, cheap, and fun.

In the mid-nineties, other manufacturers were already making big bore standards with inline four-cylinder engines. It was kind of the last hurrah of the heyday of the “UJM” concept that had dominated 80s Japanese motorcycle sales. Most of these were air-cooled, as they had been since the 80s.

There were the occasional liquid-cooled ones, like the Honda CB1000 “Project Big One”, which was based on the Honda CBR1000F. It was only sold from 1993-1994 though.

But the 1992 Kawasaki Zephyr 1100, for example, was air-cooled. So was the Yamaha XJR1200.

It was in this context that Suzuki released the Suzuki GSF1200 Bandit, also known as the Suzuki Bandit 1200, in 1995. They made it intentionally cheap and moderate-spec (low-spec for a bike of its size), and it sold really well.

For the motor of the Bandit 1200, Suzuki built upon an engine they already had — the one in the (air/oil-cooled) Suzuki GSX-R1100. Yes, that’s a superbike, but Suzuki had their way with the motor. Suzuki took the GSX-R1100’s engine, bored it out for 30 more cc, and re-tuned it for much more mid-range torque, dropping peak power by about 30% in the process.

Suzuki shortly thereafter abandoned the GSX-R1100 sportbike for the now-classic GSX-R1000 line — a line of bikes that was more powerful AND much lighter. But they kept the engine of the 1100 alive in the Bandits, which went on to evolve on their own.

After Suzuki released the Bandit 1200, other manufacturers started re-thinking their strategies. Kawasaki released the liquid-cooled ZRX1100 and Honda made its CB1300 (which didn’t make it to the US). The ZRX1100 gave way to the ZRX1200 but Suzuki abandoned the line after that. Honda kept making the CB1300 for a long time, though.

See the guide to big-bore four-cylinder motorcycles here.

Lines get a little crossed, because Suzuki also released its GSX1400, intended to be a bigger sibling to the Bandit 1200 and to compete more directly with the big fours from the other Japanese manufacturers.

As great a bike as the GSX1400 was (and is), Suzuki discontinued its class in 2008, but kept iterating on the Bandit until 2015.

The Bandit line lasted for a solid two decades before Suzuki replaced it with the GSX-S line from 2016. The GSX-S motorcycles are based on the engines from the mid-2000s GSX-R1000 and GSX-R750. They’re great motorcycles — higher power, higher revving, sportier and lighter — but that doesn’t diminish how good the Bandits were.

What makes the Suzuki Bandit line special is that they represented — particularly the faired types — the emergence of a class of bikes that were intended to be good for everything.

Suzuki Bandit Model History — in a nutshell

Below is a table of how the core specs changed between the models of the Suzuki Bandits. I’ve also included the GSX1250FA, even though it dropped the “Bandit” name, because it’s extremely similar to the GSF1250.

| Model | Bandit 1200 Gen 1 (GSF1200 / GSF1200S) | Bandit 1200 Gen 2 (GSF1200/GSF1200S) | Bandit 1250 GSF1250 / S | GSX1250FA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | 1995-2000 | MY2001-2006 (From mid-2000) | 2007-2016 | 2010-2016 |

| Capacity (cc) | 1157 | 1157 | 1255 | 1255 |

| Bore & Stroke (mm) | 79 x 59 mm | 79 x 59 mm | 79 x 64 mm | 79 x 64 mm |

| Compression ratio | 9.5:1 | 9.5:1 | 10.5:1 | 10.5:1 |

| Induction | Mikuni BSR36 Carburettors | Mikuni BSR36 Carburettors (new TPS) | Fuel-injected, 4 x 36mm throttle bodies | Fuel-injected, 4 x 36mm throttle bodies |

| Cooling | Air/oil cooled | Air/oil cooled | Liquid-cooled | Liquid-cooled |

| Peak power | 71 kW / 96 bhp / 97 PS @ 8500 rpm | 74 kW / 99 bhp / 100 PS @ 8500 rpm | 70.5 kW / 96.5 bhp @ 7500 rpm | 70.5 kW / 96.5 bhp @ 7500 rpm |

| Peak torque | 96 Nm / 71 ft-lb @ 4000 rpm | 93 Nm / 69 ft-lb @ 6500 rpm | 108 Nm / 79.7 ft-lb @ 3500 rpm | 108 Nm / 79.7 ft-lb @ 3500 rpm |

| Transmission | 5-speed | 5-speed | 6-speed | 6-speed |

| Instruments | Twin gauges, mechanical | Twin gauges with mini LCD | Twin gauges (tacho + LCD) | Large tacho + LCD |

| Ride aids | ABS (1997 onwards, SA model) | ABS (option) | ABS (option, standard on S model) | ABS |

| Brakes | Dual 310mm, 4-piston calipers | Dual 310mm, 6-piston Tokico calipers | Dual 310mm floating discs, 4-piston calipers | 2 x 310mm discs, 4-piston Tokico calipers |

| Front Suspension | 43mm conventional fork, preload adjustable | 43mm conventional fork, preload adjustable | Conventional 43mm Showa fork, preload adjustable | Conventional Showa fork, preload adjustable |

| Rear suspension | Monoshock, preload / rebound adjustable | Monoshock, preload / rebound adjustable | Link-type, Showa shock, adjustable preload and rebound damping adjustable | Link-type, Showa shock, adjustable preload and rebound damping adjustable |

| Variants | N (Naked/original) S (bikini fairing), 1996-onward SA (fairing + ABS), 1997-onward | N (Naked/original) S (bikini fairing) | S (bikini fairing): Standard ABS | Full fairing only |

The GSX1250FA is essentially a Suzuki Bandit 1250 with a few exterior changes and some different instruments — the engine and chassis are the same.

The Engine of the Suzuki Bandit 1200 / 1250

Regardless of the generation of the Suzuki Bandit 1200 / 1250 you get, you loosely get a big, four-cylinder engine that makes ~70-75 kW (~90-100 hp) of peak power (with ~95-110 Nm / ~70-80 lb-ft of peak torque).

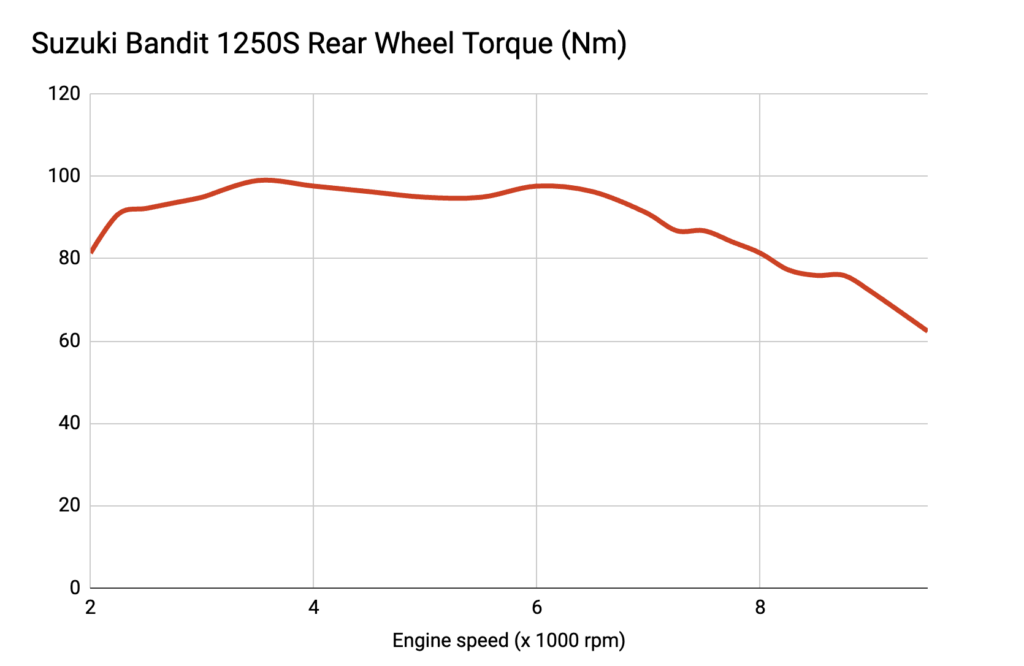

But what you always get is an engine with a big, fat torque curve. These motors make torque everywhere. Everywhere!

Universally, on all the big Bandit motorcycles, between 2000 and 6000 rpm, there’s a really wide plateau of torque. The fun part is you can hold onto it beyond there.

The GSF1200’s torque curve looks quite similar, just a little bit lower down than that of the 1250. Neither bike feels low on torque.

And there really fun part is that “there’s money in the banana stand”. Cycle World pored a measly US$1400 into their Project Suzuki Bandit 1250, giving it an exhaust, a better air cleaner, and a basic fuel controlling system. After removing the O2 sensors and the secondary butterflies and then running on a dyno, they extended the plateau of torque all the way out to the redline, and gave their 1250 a whopping 27 hp (20 kW) more peak power, bringing it in line with the competition.

This solves one of the problems of the Suzuki Bandit if you’re a sporty rider who likes to rev engines out a little. Personally, I like to hear four-cylinder engines sing, so it’s a bit disappointing to rev out a big Bandit and for the party to start to come to an end around 6000 rpm. Knowing that there’s easy gains to be had alleviates that disappointment slightly.

One of my favourite things about the Suzuki Bandit’s engine is the noise it makes. It’s very underrated. I don’t know why the regular inline four-cylinder engine isn’t more appreciated. I know, people like the roar of a twin. But the high-rpm wail of a four-cylinder motorcycle sounds like a banshee from hell, like the wail of a GP bike. Sure, they’re a little boring down low — but have you heard one with a full exhaust, at full song?

The Bandit’s engine sounds at mid RPMs to me as good as that of my Hayabusa’s. Sure, it might not make it to 11000 rpm, but then, neither do I on most days… other than briefly, anyway! It sounds really great in the 5-7000 rpm range.

The final point I want to make about the Suzuki Bandit’s engine is reliability.

The Bandit 1200 or 1250 is so torquey and so reliable that the Bandit models — particularly the nakeds — have been fan favourite stunt bikes. People will change the sprockets (and the chain) and wheelie them forever. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing for the engine, but do check the gearing, and check the front suspension for signs of abuse from hard landings.

Suzuki Bandit Models

Since the Bandit has been around for a while, let’s look at a brief evolution of the models, starting with the carburettor fed ones and coming into the present day.

Suzuki Bandit GSF1200 First Gen (1995-2000)

Suzuki released its first Bandit GSF1200 in 1995. This is where it all started!

Like many big naked bikes, Suzuki based the Bandit 1200’s motor on the engine of a superbike, the previously most recent air/oil-cooled Suzuki GSX-R1100, which was replaced by the liquid-cooled GSX-R1100 by the time of the Bandit.

You can see a big radiator at the front of the original Suzuki Bandit 1200 — that’s an oil cooler, not a liquid coolant radiator.

Suzuki bored the GSX-R1100’s 78 mm cylinders out to 79mm, increasing the displacement from 1127 to 1157 cc, just enough to round it up to 1200. It’s still a fairly basic motor, with fuelling by four Mikuni carburettors, though with dual overhead cams and four valves per cylinder.

Even though the Suzuki Bandit 1200 revs to 10500 rpm (its redline starts at 11000 rpm per the tachometer), torque starts to peter off significantly at the 8000 rpm point.

Speaking of redline, one way in which the original Bandit 1200 is the best is the instrument cluster. Now, I know this is editorialising, and maybe you are a fan of TFTs. But I just love me some twin gauges. And the original Bandit 1200 (plus others of its generation, like the 600) was the only one to have it.

If you get some work done on the motor — an exhaust and intake, plus re-jetting — it’s possible to up the power of the Bandit 1200 by 15-20% fairly easily. Owners on forums show torque gains across the whole torque curve, resulting in more power everywhere — so torque still drops off at the top, but it drops off to a higher number.

Like the engine, the rest of the Suzuki GSF1200 Bandit is pretty basic. At the front there’s a non-adjustable conventional (not upside-down) fork. The frame is a basic steel double cradle, which works and looks nice, but is heavy.

For 1996, Suzuki released the first Bandit 1200S, a.k.a. GSF1200S.

The GSF1200S is, as you can tell from the above image, a GSF1200 with a bikini fairing. It looks pretty good! This is generally a class of motorcycle that used to be popular but now has all but been replaced by more upright adventure sport touring motorcycles.

The Bandit GSF1200S looks good, but unfortunately, I’m not really a fan of that style of headlight (it looks like a toe), and so if in some hypothetical world I was deciding between two generations of Bandit 1200s identical in all but model year, I’d pick a 2nd gen just on aesthetics.

What’s interesting about the Suzuki Bandit 1200S / GSF1200S is that it’s one of those bikes that could potentially be the only motorcycle in your stable.

Multi-purpose motorcycles are hard to sell. They’re bikes that don’t excel at any one thing — they’re not track bikes, not dirt bikes, not touring bikes, and not city commuters. But they wear multiple hats.

These days, motorcycles achieve their multi-purpose promises through ride modes and configurability. But the Bandit 1250S is that out of the box. It has usable torque down low, for low speed work, and lots of pull up high, for fun times on weekends. It has an upright seating position that’s in a sporty-looking chassis with a windscreen. And it has enough character to keep any commuter happy (as long as you’re happy with an inline four).

Both versions of the original Bandit (fairing or otherwise) deliver on the same promise made by all Bandits since then. They have a huge amount of torque that starts right from 2000 RPM. Even though the dyno says it peaks higher than the second gen, dynos show that the peak is barely higher than the torque available down low — it’s just a technicality.

The fairing coverage isn’t fantastic, but the windshield is extendable if you need it.

These days, early-gen Bandits are relatively rare only because they became popular as stunt bikes! Cheap, torque heavy, and cheap, many of them were geared down and held aloft for long periods. So they’ve been abused a bit. Just bear that in mind.

Suzuki Bandit GSF1200 / S Second Gen (2001-2006)

Suzuki released the second gen Suzuki Bandit GSF1200 in mid-2000 for the 2001 model year.

The second gen Bandit 1200 shares a lot with the first gen. The engine and chassis are fundamentally the same. But Suzuki updated a lot of important stuff, starting with aesthetics, giving the 2nd gen Bandit 1200 generally sharper looks — particularly in the S model.

But Suzuki did modify the engine, giving it revised cam timing and also adding a throttle position sensor, allowing for more fine tuning of the still carburettor-fed engine. On paper, they did squeeze out a little more power, and also managed to pull the peak torque to earlier (peaking at 3800 rpm per the Cycle World dyno). Still, the 2nd gen Bandit 1200 has the same characteristic as the first — torque everywhere.

Suzuki updated the clutch, giving it a heavier clutch spring, but also giving it an increased diameter slave-cylinder clutch piston, leaving overall clutch feel quite similar.

Suzuki also gave the second gen Bandit 1200 more fuel capacity, increasing the fuel tank size from 19L / 5.0 US gal to 20L or 5.3 US Gal. It’s not much, but it’s something!

The Suzuki Bandit 1200 — whether gen 1 or gen 2 — is not a fire-breathing monster of a motorcycle. It’d never convert someone from their hard-edged sportbike. But it’s definitely a motorcycle that you can take a pillion on and have fun with.

Suzuki launched the 2nd gen contemporaneously with the Bandit 1200S with a bikini fairing. It’s similar to the earlier GSF1200S, but the 2nd gen Bandit 1200 looks a lot sharper and less dated. To my eye, it looks period, and not ugly by any means.

Suzuki also updated the instrument cluster for the 2nd gen GSF1200. Out with the twin gauges, in with twin clocks — but one of them an LCD.

Suzuki discontinued the Bandit 1200 in 2005, but there was still some new old stock that sold in 2006.

Suzuki Bandit GSF1250 / S (2007-2015)

For 2007, Suzuki updated the Bandit again, releasing the Bandit 1250.

The Suzuki Bandit 1250 was a huge update over the Bandit 1200. It got, in short, a bigger-capacity engine that’s now liquid-cooled and fuel-injected. It makes around the same amount of peak power, but there’s even more torque everywhere.

There’s nothing wrong in theory with carburettors. That is, until you leave the bike for a while and they gum up (more a fault of fuel than the carburettors, but that doesn’t stop us having to have the things cleaned), or they leak, or something needs adjusting when you change an exhaust pipe (which is technically easier than a remap, but is also fiddlier).

In fact, one advantage that most carburettor-fuelled engines have is the lack of low-RPM lag that you get on factory leanly-tuned fuel-injection systems.

But fuel injection just goes. I like it for being something I never have to think about. Maybe I’ve been lucky, but I also tend to almost never hear about faulty injectors (I do sometimes, though). That said, I acknowledge that they often do need a tune — particularly if a semi-obligatory exhaust has been added.

Suzuki made plenty of other updates to the Bandit 1250 aside from to the fuelling. They gave the Bandit liquid cooling, a counter-balancer in the engine (to smooth it out), six-speed transmission (living in the future!), and dual throttle valve fuel injection.

Aside from a beefier chassis, Suzuki kept the rest of the motorcycle fundamentally the same — simple and economical. It still has a simple-as-heck double downtube frame and conventional (non-inverted) suspension.

As a testament to the re-styling of the Bandit for the 2nd gen, the second-gen Bandit 1250S looks quite similar to the earlier gen.

When I see the Bandit 1250 (or GSX1250F), I think “Looks right for the period”. What that means is that it doesn’t have the razor-sharp looks of the latest gen of bikes, but it also doesn’t look weird and ugly. It just looks like a mid-2000s bike. Never mind that they made this thing until the mid 2010s!

These days, the Suzuki Bandit 1250 is super cheap for what you get — a very reliable, decent looking, and capable everyday sport bike. Yes, it’s heavy — curb weight is over 250 kg or 560 lb. This puts it squarely in “Hayabusa” territory. But the Hayabusa has around twice the peak horsepower.

So why would you pick a Bandit over a Hayabusa? Well, let’s start with the fact that a Bandit will often be less than half the price on the used market. Go confirm this now in your local market, say looking at two 2015 models — I just did.

Used Bandits might be getting up in miles, because people will tend to ride them more, and that’s your second reason — handlebars and a torque-rich engine mean that it’s more likely to be an everyday rider (unless you’re a diehard sport bike rider).

And the third reason is that minor crashes on a Suzuki Bandit 1200 or 1250 are no biggie. Even if you damage it, it’s built out of such sturdy and basic components that it’s relatively easy to fix, especially when price comparing against components.

The main contender against the Bandit 1250 is the 1250S, and its main rival is, in turn, the Suzuki GSX1250FA.

Suzuki GSX1250FA

The Suzuki GSX1250FA is technically not a Bandit, as it doesn’t have “Bandit” in the name, but rather a string of letters and numbers. Despite this, it’s a very similar bike to the Bandit GSF1250. There’s a bit better fairing protection, and a bit less access to the engine when it’s time to inspect things.

The reason I want to include the GSX1250FA here is that I think it’s a really good looking and understated bike.

It’s rare for a motorcycle with a full fairing to both look good and to also be usable in everyday riding conditions. This class of sport tourers has almost vanished, as I mentioned earlier, mostly replaced by sport adventure tourers — with upright seating positions and wide, almost dirt bike-like handlebars.

But the Suzuki GSX1250FA looks good. Not like a full-on race bike, of course, but the fairing looks appropriate, despite the handlebars. There are few bikes for which this is true.

Suzuki also gave the GSX1250FA heavier fork springs with firmer rebound damping and an additional radiator fan.

Plus, for the GSX1250A, Suzuki upgraded the instrument cluster, giving it reserve mileage countdown (luxury!) and overall a different format (Suzuki had kept it the same between the 2nd gen Bandit 1200 and 1250, aside from a lower redline).

The Suzuki GSX1250FA also came in some very good-looking special editions near the end of its life.

Suzuki has always been good with paint on even their mid-range motorcycles. I’ve seen plenty of SV650s with great colour schemes and good paint jobs. My Hayabusas were all stunners, but that’s to be expected of high-end bikes.

But if you can find a special edition Suzuki GSX1250FA, it’d be worth a look.

Riding the Suzuki Bandit (of any gen)

The Suzuki Bandit is worth a look because it’s just so much better than the sum of its parts.

If you hear things like “double downtube frame”, “non-inverted forks”, and “250 kg / 550 lb”, you might think… bleah. That sounds like a recipe for slow, heavy, and cumbersome.

Maybe it’s the low expectations set by that mix of ingredients that leads most riders of the Suzuki Bandit — of any generation — to be surprised. It really just all works together, and that’s what makes the Suzuki Bandit special — it’s cheap, but it’s still good.

Firstly, the Suzuki Bandit’s engine is just such a gem. Ask any newbie what the difference between a V-twin and an inline four is, and they’ll say something like “V-twins have more low-end torque”. While that might be true generally, comparing a classic V-twin (a cruiser) with an iconic inline four (a superbike), the Suzuki Bandit is the exception that proves the rule.

The Suzuki Bandit bikes all have torque from very, very low. The effect of low torque in an engine that can still rev above 7000 rpm is really interesting. It makes the Suzuki Bandit hard to stall, thus easy to ride. But it also makes it easy to ride fast.

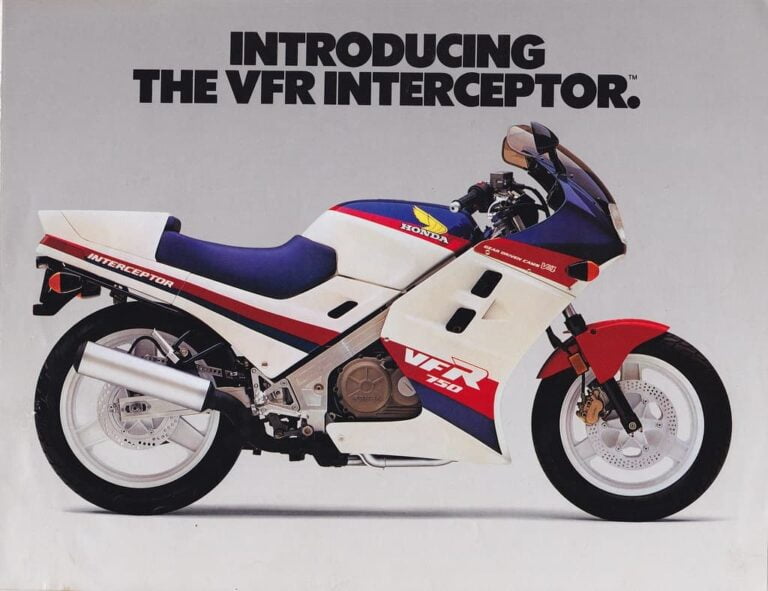

There are bikes in the same class as the Bandit that make more power on paper, but which don’t feel as fast. For example, the Honda VFR800, which has a bit more power, and a bit less weight. Yes, I know the engine is 2/3 the size, and that’s an important point. The Bandit makes use of its cubes not to keep pushing the high-end power envelope, but to round out low-end torque. The result is that it’s easy to launch and to squirt out of any corner, which makes it just easy to go fast.

At low speeds, having low-end torque and wide bars makes the Bandits very easy to ride around parking lots or navigate urban streets. I’ve stalled superbikes (especially in the first few miles of ownership) trying to figure out launch points. It’s very nerve-wracking to launch a superbike I’m unfamiliar with, especially when launching into a turn (e.g. off a traffic light). But with the Bandit, there’s zero stress.

When underway, the Bandit still does feel heavy (because I’ve had the fortune of riding some very lightweight sport bikes), but never too heavy. It handles relatively well and easily. The fork is soft, and does dive a little under breaking — but the counterpoint is that it’s extremely comfortable. The whole bike is comfortable!

That said, the Suzuki Bandit — even the latest-generation 1250 Bandits / GSX1250FA — is not a sport bike.

It’s as heavy as my Hayabusa, as I mentioned, but has half the peak power. And it has much more low-end suspension and braking. People say Hayabusa isn’t a sport bike just because it’s heavy and not that impressive next to its GSX-R1000 cousins; well, the GSX1250FA isn’t a sport bike, period.

That said, with the little amount of money you have to spend to get a GSX1250FA, there’s no reason you can’t get yourself a little closer…

A well-done tune on a Suzuki 1200 / 1250 can smooth out the torque curve, making it actually satisfying to rev it to near 10000 rpm (redline on the 1250 is 9500 rpm). You probably will rarely make it up there. But you will have the option!

One other way in which the Suzuki Bandit definitely isn’t a sportbike is in its handling. The handlebars and the soft suspension generally create a feeling of distance from the front wheel, in spite of the quick-steering rake and trail. You’re high up there.

This isn’t to say that the Bandit handles badly. It’s just that… I didn’t feel as connected to the road as I do on a naked roadster or on a superbike. The weight of the Bandit just adds to that.

It’ll handle. It’s just not a full-on sport bike.

So, in general, the Bandit isn’t a motorcycle that you should buy if you really like revving past 10K or if you want to bang it through corners. (The FZ1S might be a better pick — see below.)

But if you’re a bit more even-handed as a rider, and are mostly concerned with the 99% of riding that’s everything other than fast corners, then the Bandit is a gem.

Suzuki Bandit GSF1250 vs Suzuki GSX-S1000 — How did it change?

Since the Suzuki GSX-S1000 motorcycles have been out for quite a number of years now, and were never that expensive, you might be thinking — shouldn’t I just drop my hard-earned cash on a more recent model?

Maybe. But it really depends on the price you find and also what you’re looking for.

In 2016, Suzuki released the GSX-S1000 and GSX-S1000F, a naked bike and a sport touring bike, replacing the Bandit 1250 and GSX1250F. Then, a few years later, they also released the Suzuki Katana, also known as the Katana 1000, or the GSX-S1000S. And most recently, there’s the Suzuki GSX-S1000GT, the sport touring motorcycle.

Here they all are in their original forms. Suzuki did a refresh in the last couple of years, but not much changed.

The first difference is the engine.

The Suzuki Bandits have an engine based on the very old GSX-R1100 superbike, a bike long gone. Since then, the engine has evolved to become a Bandit engine more than anything else.

The Suzuki GSX-S line, on the other hand, is based on the K5-K8 Suzuki GSX-R1000 motor. That was a relatively long stroke motor in GSX-R genealogy, and people liked it for having a broad, very useable torque curve.

Even though Suzuki moved on to shorter-stroke, higher-revving, and thus higher-power motors for the GSX-R1000, the K5-K8 engine lives in on a variety of GSX-S models. It still makes loads of power (112 kW / 152 hp at 9250 rpm), which is plenty, without meat in the midrange to make most people happy.

See here for my review of the 2017 Suzuki GSX-R1000R.

Suzuki updated the style of the GSX-S from the Bandit, too. There’s no more “round headlight” variety of motorcycle; the closest thing to a retro is the re-imagining of the Suzuki Katana.

And what a retro the Katana is! I find it very hard to not plonk down for one, especially for one in glorious glass sparkle back. Well, in any colour.

Suzuki upgraded everything on these bikes.

- The engine, as mentioned, makes around 50% more peak power — though you have to rev it more to get there.

- Gone is the double downtube frame; the Suzuki GSX-S1000 bikes have a more modern twin spar aluminium frame.

- No more conventional forks; the Suzuki GSX-S1000 motorcycles have inverted forks with full adjustability.

- And the brakes, while they were good already for a budget bike, are now Brembo monoblock radial-mounted calipers.

On top of that, the GSX-S1000 motorcycles are universally lighter. For example, the Suzuki GSX-S1000F, which also has a full fairing, weighs 214 kg / 472 lb, over 40 kg lighter than its predecessor, the GSX1250FA.

Essentially, the GSX-S bikes are sportier in every way. And they’re not even expensive, particularly if you look for early models (if they’ve had their fuelling issues sorted out). So really, the decision comes down to: Do you want the heavy, early torque of the Bandit, with the costs of its weight and style, or do you want the more top-heavy sportiness of the GSX-S, with better handling to suit?

Alternatives to the Suzuki Bandit line

Generally speaking, the main alternatives to the Suzuki Bandit are the four-cylinder naked or sport touring motorcycles that are based on a superbike — even if that association has faded with the passage of time.

The Bandit has existed for so long that it has tons of alternatives. But I’ll try to briefly mention a few below.

Kawasaki ZRX1200 / Ninja 1000

Right off the bat, I’ve had to mention two motorcycles in one section!

The Kawasaki ZRX1200 (which came in a few incarnations, like R for naked and S for fairing-equipped) is a now classic bike that’s thin on the ground. They’re hard to find at reasonable prices, especially if you want a green one. The ZRX was only ever a carburettor-fed motorcycle.

Aside from style, which the ZRX oozes, they don’t offer anything particularly over a Bandit. Yes, you can probably make them go faster, but if you wanted a fast bike, you’d pick something else.

You could also say the Kawasaki Ninja 1000 is an alternative, as a comfortable / utilitarian sportbike that overlapped with the latter years of the Suzuki Bandit and GSX1250FA.

The Kawasaki Ninja 1000 is, overall, a more powerful, slightly lighter, and better-equipped bike. It has always made around 105 kW / 140 hp at around 9500 rpm from its engine that was also based on an earlier-generation Kawasaki superbike.

Kawasaki has always been pretty early with tech on its Ninja 1000s, too, with ABS, traction control, and ride modes from the 2014 generation.

See here for the Kawasaki Ninja 1000 buyer’s guide.

Yamaha FZ1 (2006-2016)

The Yamaha FZ1 is one of those bikes that’s way too good for the paltry price you’ll pay used, these days. This is a bike that’s basically at BMW S 1000 XR levels of comfort and performance (slightly less power, but less weight, too). They’ll outpace many modern superbikes in performance, are a doddle to ride in everyday conditions, and you can get them for a song. I may just see one in my future, if the opportunity presents itself.

See here for more about the Yamaha FZ1 (both gens).

There are two versions of this the Yamah FZ1: the naked bike and the FZ1-S Fazer. Depending on which version of the Suzuki Bandit you’re looking at, you might be interested in one or the other.

The Yamaha FZ1 (whether naked or Fazer) has as its engine the 998 cc 2nd gen Yamaha YZF-R1’s motor (from the 2004 generation). That generation R1 was fuel-injected but also had five valves per cylinder, something ditched in later years, pre-crossplane.

See the Yamaha YZF-R1 buyer’s guide

For the FZ1, Yamaha detuned the engine slightly, altering the camshaft profiles and increasing the weight of the flywheel, also reducing the compression ratio.

But the net effect of the down-tuning isn’t even that crazy — the Yamaha FZ1 Fazer still makes a healthy 150 hp (148 bhp / 110 kW) at 11000 rpm. That’s a huge amount of power! Couple it with the FZ1 Fazer’s relatively light wet weight of 221 kg / 487 lb, and this is a wild ride.

The catch is that the Yamaha FZ1 Fazer’s power delivery is much peakier. It makes less torque down low compared to the Suzuki Bandit of any model, and more power higher up. It’s a bike on which you’ll have to shift and rev.

So, this might suit you if you have sporty inclinations, but that’s a different target market to that of Bandit-riding hooligans.

Sum Up

If you’re after a cheap, functional motorcycle with loads of everyday usability, a nice-sounding four-cylinder engine, rock-solid reliability and easy repairability, then it’s hard to go past the Suzuki Bandit, especially the fuel-injected 1250 generations.

Yes, other bikes might be lighter and faster, but the Bandit is a steal. Even if you just save a couple of thousand over a more recent bike, that money goes towards a full set of the coolest gear you could find.

The one catch is that I don’t really think that the Bandit or GSF bikes will become classics. So, don’t overpay for one, and don’t expect it to become an investment.

But if you’re after a bike that won’t let you down and that will serve you faithfully in a lot of contexts for a long way to come… the Bandit is a very low-budget way to get there.

Dana, when you reference a “tune” as to an unmodified bike that has a little throttle hesitation related to leanness from the factory -like my Hayabusa and CBR954 – what are you contemplating? There is a unit with three dials that is very simple (Dobreck performance) and there is a dealer dyno tune and others units in between.

I mean a dealer dyno tune. I’ve mucked around with things like Booster plugs, and I think they mostly gave a placebo effect. But dealer dyno tunes, though expensive, produce indisputable results. Note — dealers/mechanics can also dial in something like a Dynojet Power Commander better than I can.

I own the GSX650F and the 1250 basically stock besides Yoshi slip ons and Healtec fuel mgmt system (and tail tidies and flush mount signals). They’re both great bikes with no issues, at 28 and 41 thousand miles — not even a drop of oil or any smoke.

Early oil change with synthetic high quality oil and a valve adjustment @ 17 and 36 thousand miles.

Love these babies and I have had a lot of bikes over my 36 years of riding. Great article.

Thanks, glad you are enjoying them. The 650 goes for a song relative to what you get.

I own a 2016 bandit 1250s which I bought new in 2017 for $7600 it was a steal back then! And since I was coming from the Suzuki M90 behemoth at 725 lbs, this bike felt as light as feather. It is my commuter bike. I look at bikes all the time and think maybe I should get a new one, then I go for a ride and ask why? I have yet to come up with a reason